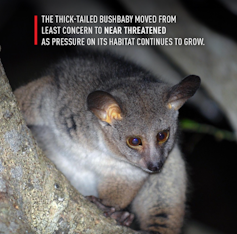

A new list of threatened mammals in South Africa, Lesotho and Eswatini shows that 11 more species have edged closer to extinction since 2016. Those that have joined the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s regional Red List for mammals at risk are: Lesueur’s hairy bat, the laminate vlei rat, the thick-tailed bushbaby, the aardvark and the African straw-coloured fruit bat. The Namaqua dune mole-rat showed one of the sharpest declines, jumping from Least Concern to Endangered. Joseph Ogutu is a statistician who researches collapsing wildlife populations in Africa. He explains that of the 336 mammals assessed, 70 are now threatened and 42% of the mammals only found in South Africa are at risk of extinction.

What does an uplisting on the Red List actually mean?

The latest, 2025 Red List is compiled by the Endangered Wildlife Trust and South African National Biodiversity Institute. If an animal is “uplisted” on the list, it has been moved to a higher extinction‐risk category.

An uplisting can reflect either:

a genuine deterioration in the mammal’s population (a real decline, worsening threats or a loss of habitat) or

that new knowledge has come to light (for example if the mammal’s numbers were previously over- or underestimated).

Read more:

Africa’s mammals may not be able to keep up with the pace of climate change

An uplisting isn’t a headline-grabbing label. It’s the science catching up to whether the risk to the mammals has worsened or not, or whether conservationists have developed more accurate ways of measuring the risk.

The latest Red List assessments are based on evidence gathered by 150 experts through the Endangered Wildlife Trust and South African National Biodiversity Institute between 2016 and 2025. Over this time, they monitored mammal species’ populations carefully through surveys and calculated how much the mammals’ habitat was shrinking (leaving them less space to live on and less chance of survival). They’ve also used the data recorded by citizen scientists who logged sightings of the mammals during this time.

This latest Red List recognises that mammals are declining because of drought, heat, water shortages and less opportunity to forage and graze.

Even previously common animals are now on the list. Does this mean southern Africa’s mammals are doomed?

The uplisting shows that humans continue to drive wildlife loss. The expanding human footprint signals that pressures on mammals will increase further, placing not only rare mammals in danger but also species that were previously assumed to be resilient.

This does not mean mammals are generally doomed. It means the margin of safety for mammals is shrinking. Without decisive, consistent action to reduce pressures on the mammals and protect their habitats, the outlook – especially for large mammals – remains bleak in a warmer world where the human population is increasing.

Read more:

Migrating animals face collapsing numbers – major new UN report

A wide range of mammal species are adversely affected, including both endemic (those only found in southern Africa) and non-endemic (those found in other places too) species. They range from less widely known bat species to well known large mammals such as the thick-tailed bushbaby and the aardvark.

Bontebok.

Courtesy Cliff & Suretha Dorse/EWT

In fact, the latest regional Red List shows that 67 mammals (about 20%) are deemed to be threatened with extinction, and 39 (11.5%) are Near Threatened. The species most in danger are those affected by where they live. In other words, how fast their habitat is changing, and how little room remains for ecological “error”. They are the mammals that can’t “move away” from change, because they can only live in a limited area.

These mammals have less protection than was earlier thought. And to make matters worse, their habitat is contested by competing land uses: cultivation, grazing, settlement, infrastructure and extractive development, often under overlapping community, private, and state claims.

I would dare say, when “common” species start becoming more at risk of extinction, it’s not a verdict of doom, it’s a stark warning, like a smoke alarm.

Some species’ numbers improved. What worked?

The Hartmann Mountain Zebra.

Courtesy Cliff and Suretha Dorse/EWT

Three species improved – the roan antelope was downlisted from Endangered to Vulnerable, while the southern elephant seal and Hartmann’s mountain zebra were both moved to Least Concern.

This downlisting is due to successful interventions. These could have included sustained conservation, which reduced the threats to these mammals. It’s likely there were more efforts to protect their habitats. Working in public-private partnerships with businesses could have helped. Even using better quality data to make better decisions would have been effective.

Read more:

Mass animal extinctions: our new tool can show why large mammals – like the topi – are in decline

The practical lesson from this is that improvement is rarely driven by one thing. Rather, it comes from ongoing measures that reduce the deaths of mammals, secure their habitat, and force managers to update tactics as monitoring shows what’s working – and what isn’t.

Downlisting isn’t luck – it’s what happens when protection is real, threats are reduced, and monitoring is good enough to prove it.

What needs to happen next?

The government, private sector and citizens need to do much more, and invest more, in protecting wildlife and habitats. The recurring trends where large land mammals are moving closer to extinction shows that not enough is being done to protect southern Africa’s mammals.

More money is needed to protect species and the kind of environment they need to live in.

There are at least three things that need to be done urgently:

Development of housing, farms, roads and energy infrastructure must be designed around the environment.

Conservation can no longer happen in isolated, fenced off islands. A landscape systems approach will protect mammals and other threatened species better. This is where reserves are connected, governments work together to protect animals that live in cross boundary areas and where conservation also happens outside park fences.

Read more:

Africa’s savannah elephants: small ‘fortress’ parks aren’t the answer – they need room to roam

Climate-proof conservation is needed. This is where conservation recognises that heat, drought and water scarcity are going to become ongoing, chronic pressures on animals as the climate heats up. They will not be rare shocks.

The uplisting of so many species shows that conservation will not be saved by better words; it will be saved by better choices – funded, enforced and maintained.

The next phase of conservation needs to be about more than just saving species. It must be about redesigning the human footprint so that mammals are assured of spaces that still have enough suitable habitat (food, cover, water), lower human pressure (less use of wild land for human purposes, conflict, poaching), and stronger protection and management (parks, well-run reserves, and some conservancies).