Looking after your brain is something that happens over many years, and new findings from the AdventHealth Research Institute point to an encouraging option. Researchers report that sticking with a consistent aerobic exercise routine may help the brain remain biologically younger. This effect could support clearer thinking, better memory, and overall mental well-being.

The research showed that adults who committed to a full year of aerobic exercise had brains that appeared almost one year younger than those of participants who did not change how active they were.

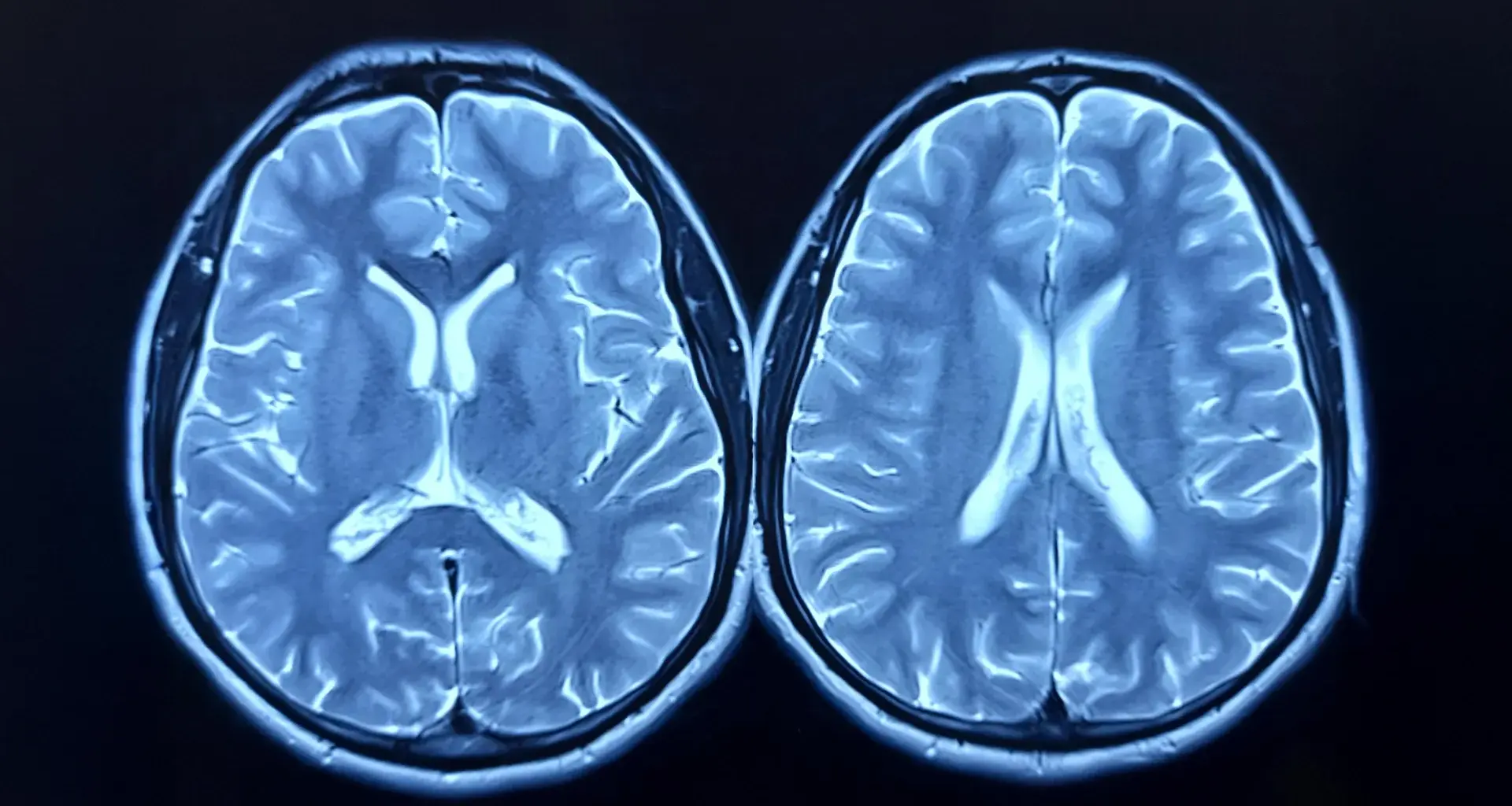

Measuring Brain Age With MRI

Published in the Journal of Sport and Health Science, the study examined whether regular aerobic exercise could slow or even reverse what scientists call “brain age.” Brain age is estimated using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and reflects how old the brain appears compared to a person’s actual age. A higher brain-predicted age difference (brain-PAD) means the brain looks older, and earlier studies have linked this measure to weaker physical and cognitive performance and a higher risk of death.

“We found that a simple, guideline-based exercise program can make the brain look measurably younger over just 12 months,” said Dr. Lu Wan, lead author and data scientist at the AdventHealth Research Institute. “Many people worry about how to protect their brain health as they age. Studies like this offer hopeful guidance grounded in everyday habits. These absolute changes were modest, but even a one-year shift in brain age could matter over the course of decades.”

Inside the Year-Long Exercise Trial

The clinical trial included 130 healthy adults between the ages of 26 and 58. Participants were randomly assigned to either a moderate-to-vigorous aerobic exercise group or a usual-care control group. Those in the exercise group completed two supervised 60-minute workout sessions each week in a laboratory and added home-based exercise to reach roughly 150 minutes of aerobic activity per week. This schedule matched the physical activity guidelines set by the American College of Sports Medicine.

Researchers measured brain structure using MRI scans and assessed cardiorespiratory fitness through peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak) at the start of the study and again after 12 months.

Exercise Linked to a Younger Looking Brain

After one year, clear differences emerged between the two groups. Participants who exercised showed a measurable decrease in brain age, while those in the control group showed a slight increase. On average, the exercise group saw their brain-PAD drop by about 0.6 years, meaning their brains looked younger at the end of the study. The control group’s brains appeared about 0.35 years older, a change that was not statistically significant. When compared directly, the gap between the two groups was close to one full year in favor of the exercise group.

“Even though the difference is less than a year, prior studies suggest that each additional ‘year’ of brain age is associated with meaningful differences in later-life health,” said Dr. Kirk I. Erickson, senior author of the study and a neuroscientist and director at AdventHealth Research Institute and the University of Pittsburgh. “From a lifespan perspective, nudging the brain in a younger direction in midlife could be very important.”

Why Exercise May Affect Brain Aging

To better understand why exercise influenced brain age, the research team looked at several possible factors. These included changes in physical fitness, body composition, blood pressure, and levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that supports brain plasticity. Although fitness levels clearly improved with exercise, none of these factors statistically explained the reduction in brain-PAD seen in the trial.

“That was a surprise,” Wan noted. “We expected improvements in fitness or blood pressure to account for the effect, but they didn’t. Exercise may be acting through additional mechanisms we haven’t captured yet, such as subtle changes in brain structure, inflammation, vascular health or other molecular factors.”

Focusing on Midlife for Long-Term Benefits

Many studies on exercise and brain health focus on older adults, after age-related changes have already become more pronounced. This trial took a different approach by targeting people in early to mid-adulthood, when brain changes are harder to detect but prevention may offer greater benefits over time.

“Intervening in the 30s, 40s and 50s gives us a head start,” Erickson said. “If we can slow brain aging before major problems appear, we may be able to delay or reduce the risk of later-life cognitive decline and dementia.”

What the Findings Mean Going Forward

The authors caution that the study involved healthy, relatively well-educated volunteers and that the changes in brain age were modest. They note that larger studies and longer follow-up periods are needed to learn whether these reductions in brain-PAD lead to lower risks of stroke, dementia, or other brain-related diseases.

“People often ask, ‘Is there anything I can do now to protect my brain later?'” Erickson said. “Our findings support the idea that following current exercise guidelines — 150 minutes per week of moderate-to-vigorous aerobic activity — may help keep the brain biologically younger, even in midlife.”

About the Researchers and Funding

Dr. Lu Wan has been a Data Scientist at AdventHealth in Orlando, Florida, since June 2024. Her previous roles include Data Engineer at the University of Pittsburgh and Biomedical Engineer at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital. She holds a PhD, completed graduate research training at the University of Florida, and studies brain aging, physical activity, and cognitive health across adulthood. She is affiliated with the AdventHealth Neuroscience Institute, a nationally recognized center for brain research and care.

Dr. Kirk I. Erickson is the Director of Translational Neuroscience and the Mardian J. Blair Endowed Chair of Neuroscience at the AdventHealth Research Institute. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and completed postdoctoral training at the Beckman Institute. Previously a Professor at the University of Pittsburgh, his work focuses on how physical activity affects brain health across the lifespan. He has published more than 350 articles, led major NIH-funded trials, and served on the U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Grant P01 HL040962) awarded to Peter J. Gianaros and Kirk I. Erickson.