Applications

22/01/2026

402 views

11 likes

Already recognised for its excellence and even adopted for operational weather forecasting, the European Space Agency’s Arctic Weather Satellite has now fulfilled its most important role. This small prototype mission has succeeded in paving the way for a new constellation of similar satellites, known as EPS-Sterna.

Launched in August 2024, the Arctic Weather Satellite was conceived and deployed in just three years, and within a tightly constrained budget – demonstrating how a New Space approach can be used to realise small satellites for Earth observation.

Crucially, the mission was primarily designed to show how a constellation of similar polar-orbiting satellites could deliver frequent observations to support very short-term weather forecasts and nowcasts in the Arctic, and around the world. This need is becoming increasingly urgent.

As climate change continues to intensify weather variability in the Arctic, the demand for more – and more frequent – data is growing, particularly measurements of atmospheric water vapour.

Concentrations of water vapour can change rapidly in this region and have a significant impact on forecast accuracy. The coverage needed cannot be achieved by a single satellite alone, but only through a dedicated constellation.

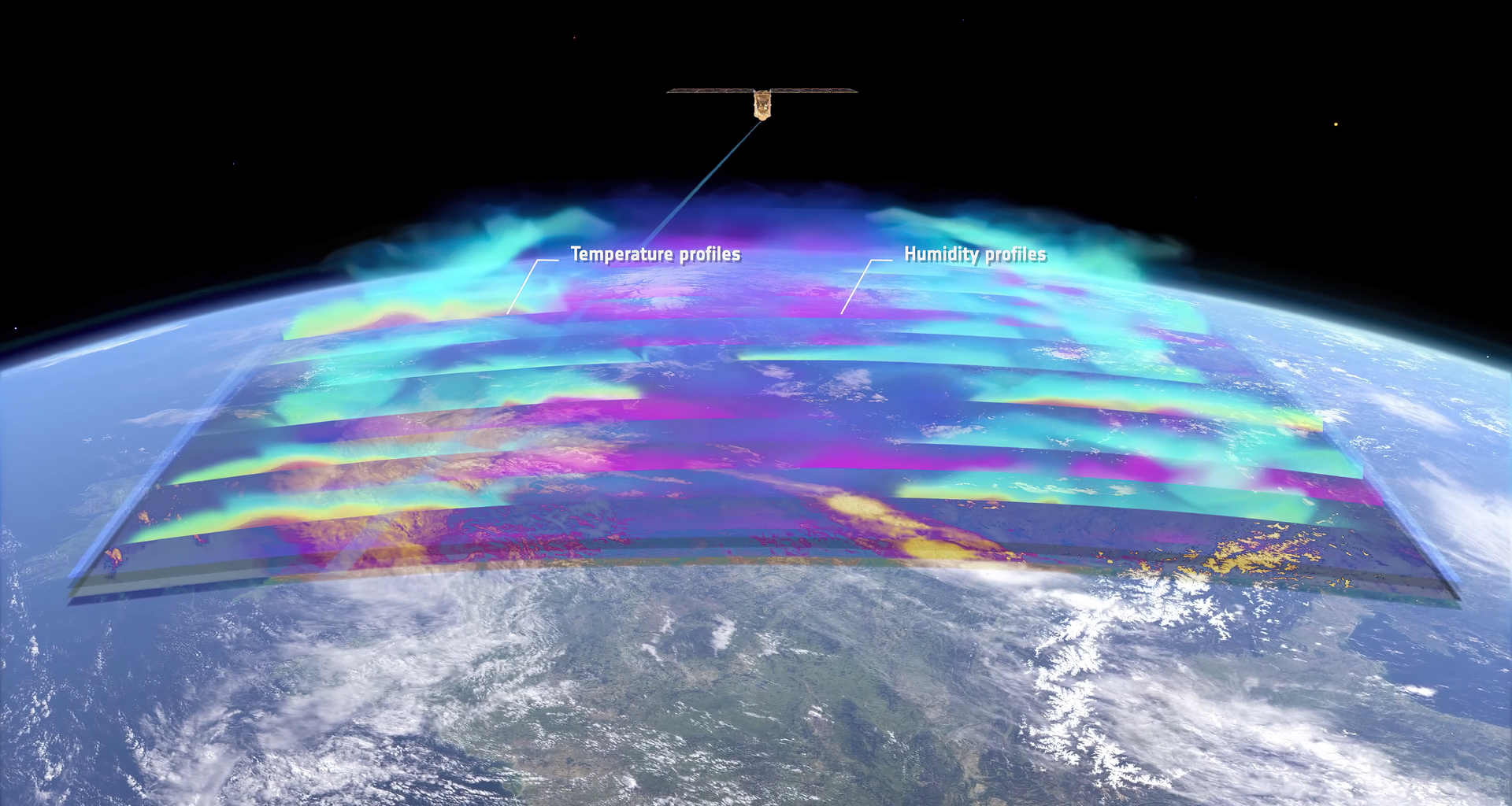

Equipped with a cross-track scanning microwave radiometer, the Arctic Weather Satellite delivers detailed measurements of atmospheric humidity along with temperature.

Arctic Weather Satellite in action

Even though it is a prototype mission, the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) deemed its data so good as to assimilate them into weather forecasts.

The data, along with numerous other observations, are merged with a short-range forecast that is guided by earlier measurements to produce the most accurate possible snapshot of the Earth’s current state. This analysis then serves as the starting point for generating weather forecasts.

Information from the Arctic Weather Satellite’s microwave radiometer complements data from similar sensors on much larger satellites provided by organisations such as the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (Eumetsat), the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the China Meteorological Administration (CMA).

This fact alone stands as a strong endorsement of the mission’s excellence and has helped to open the door for a constellation of similar satellites – and as such Eumetsat has confirmed that the Eumetsat Polar System – Stena (EPS-Sterna) will go forward, with the aim of launching the first satellites of the constellation in 2029.

Arctic Weather Satellite animated patch

ESA’s Arctic Weather Satellite Project Manager, Ville Kangas, said, “We are extremely proud of the Arctic Weather Satellite mission and my thanks go to the many who have been involved. We developed this innovative satellite under very tight time and budgetary constraints, proving that this approach can be adopted for a constellation of such satellites.

“And, in orbit, the satellite has not only performed well, but exceeded expectations by actually being used operationally for weather forecasts, which wasn’t on its list of requirements – only to show that it could.

“The news that Eumetsat will now go forward with EPS-Sterna is indeed great news, and we are looking forward to developing and building the constellation in cooperation with Eumetsat.”

The constellation will comprise of six satellites – and the satellites will be replenished twice during the lifetime of the mission to ensure the continued delivery of data until at least 2042. In addition, there will be two satellites as spares, leading to a total of twenty satellite to be built.

ESA will manage the procurement of the Sterna satellites – a cooperation model similar to Europe’s other meteorological missions, namely the geostationary Meteosat and the polar-orbiting MetOp missions.

The formal agreement between ESA and Eumetsat is to be signed shortly.

EPS-Sterna will deliver global observations, with most data available within around an hour and revisit times of less than three hours for the same location on Earth. This will be a major step forward compared with current polar-orbiting satellite systems, which typically observe the same area only twice a day.

The increased observation frequency will significantly enhance the monitoring of rapidly evolving weather, improving forecasts of severe events in vulnerable regions such as the Mediterranean, while also closing critical data gaps over the Arctic – the fastest-warming region on Earth and a key source of weather systems that affect and often intensify over Europe.

Fun fact: Sterna is the Latin genus for the Arctic Tern, a bird known for its extensive migrations, reflecting the satellites’ polar orbits.

Like