This week in Farnborough, near London, hundreds of arms company representatives mingled with military officers and government officials from around the world.

Among them were representatives from the Irish Defence Forces and Department of Defence.

They were attending the annual International Armoured Vehicles Conference, which bills itself as “the largest, most influential gathering of the global armoured vehicles community”.

Between workshops on tank tactics and a drinks reception hosted by the Italian aircraft company Leonardo, delegates toured a sprawling exhibition hall containing examples of the latest in armour technology.

Of particular interest, at least to the Irish delegates, was a group of French vehicles made by the companies Thales and KNDS. These included the Griffon, a gigantic six-wheeled armoured personnel carrier; the Serval, a smaller four-wheeled armoured car, and the Jaguar, a tank-like “armoured fighting vehicle” equipped with a large turreted gun.

A board of Irish civilian and military officials responsible for designing the future armour requirements for the Defence Forces has focused on these vehicles as candidates to replace its current fleet of armoured personnel carrier s, which are approaching 30 years’ service, and its now retired fleet of 27 light armoured tactical vehicles.

Officials have also considered Finnish- and Swiss-made vehicles, but the French offering is believed to be the most popular.

The resulting contract could be worth as much as €500 million, making it one of the largest single acquisitions in Irish military history.

This would make France, and in particular Thales – which is part owned by the French state – the undisputed winner from Ireland’s commitment to increase military spending by 50 per cent to €1.5 billion and eventually 300 per cent to €3 billion, without accounting for inflation.

Thales has already won other highly valuable contracts from Ireland. In 2024 it was selected to provide 6,000 “software defined radio systems” to the Defence Forces at a cost of €76 million. Last year the defence giant was selected to supply a €60 million sonar system to the Irish Naval Service, which will allow it to detect, for the first time, underwater threats.

French president Emmanuel Macron at the Thales pavilion during the International Paris Air Show. Photograph: Mohammed Badra/Pool/AFP via Getty

French president Emmanuel Macron at the Thales pavilion during the International Paris Air Show. Photograph: Mohammed Badra/Pool/AFP via Getty

Undoubtedly, the biggest prize for arms companies is the upcoming contract to supply Ireland with a military radar and air-defence system, allowing authorities to detect airborne threats anywhere in the country.

Last year the Coalition announced a government-to-government deal with France for the supply of the system. This means Thales, which specialises in such systems, is almost certain to get at least part of the contract, which could be worth more that €600 million.

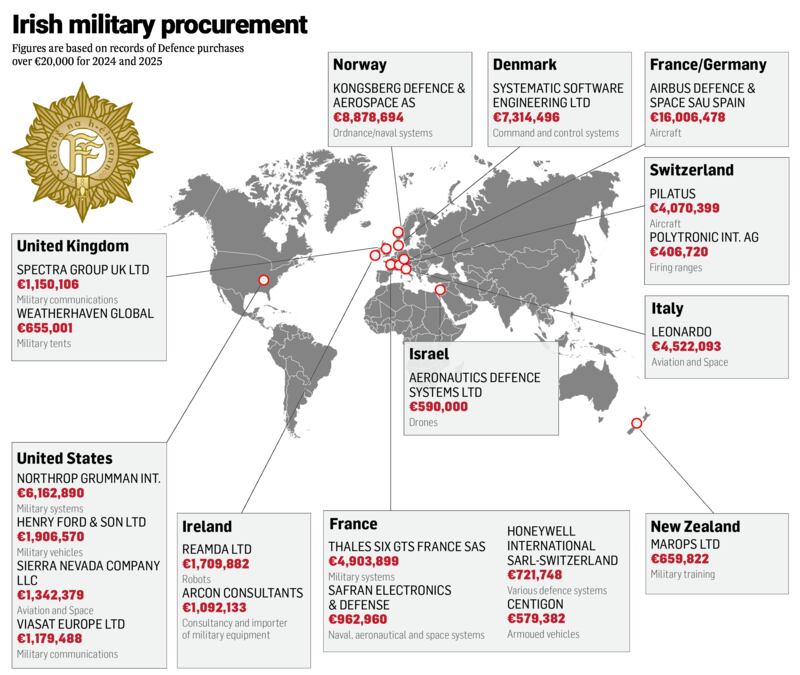

Graphic: Paul Scott

Graphic: Paul Scott

Other French companies will also benefit, including MBDA, which is favoured by Irish officials to supply ground-to-air missiles and anti-drone technology.

Additionally, the French aircraft manufacturer Dassault recently won the contract to supply a €53 million mid-size jet to the Air Corps for evacuation missions and transporting Government officials.

Which country tops the table?

If things proceed as expected, Ireland will rely on French companies for a huge proportion of its heavy-duty military equipment.

By 2030 France could be in receipt of almost €2 billion in Irish defence contracts, a staggering figure considering the entire Irish defence budget for this year is €1.48 billion.

In some ways this is no surprise. In recent years France has been one of a small number of big military suppliers to Ireland.

An analysis of significant military purchases (of more than €20,000) in 2024 and 2025 shows Ireland paid €51 million to French-headquartered companies, putting the country comfortably at the top of the table.

Other big French suppliers include Airbus, which provided Ireland with three maritime patrol and military transport aircraft, at a cost of €350 million; the Safran Group, which supplies various flight systems; and Centigon, which specialises in armoured vehicle parts.

Most other suppliers are also European companies. During the two-year period, €9 million was paid to the Norwegian company Kongsberg Defence and Aerospace, for various naval systems, while €10 million was paid to Leonardo in Italy for helicopter-related services.

Another big beneficiary was from a fellow neutral country. Pilatus, which is headquartered in Switzerland, previously supplied the Air Corps’ fleet of four PC-12 utility aircraft and its eight PC-9 armed turboprop training aircraft. It received €9.5 million in 2024 and 2025, mostly for parts and maintenance for these aircraft.

Several UK companies are also big defence suppliers to Ireland, including various maritime companies that sell naval systems as well as a company selling military tents.

US president Donald Trump arrives to address troops at the Al-Udeid air base southwest of Doha on May 15th, 2025. Photograph: Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty

US president Donald Trump arrives to address troops at the Al-Udeid air base southwest of Doha on May 15th, 2025. Photograph: Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty

Given its large arms industry, there is a surprising lack of arms companies from the United States among the top 20 suppliers.

US companies accounted for €10.5 million in big contracts during the period analysed. A large portion of this was for civilian-type vehicles from Ford and for providing training to Air Corps pilots at US facilities.

It is understood US companies are not in the running for any of the big upcoming contracts.

“There is obviously a major concern about buying anything American at the moment for fear the contracts could be torn up,” says former TD and Army Ranger Wing commandant Cathal Berry, in reference to the Trump administration’s erratic approach to international relations.

Berry says French companies were an obvious choice for procurement due to the country’s proximity, its close relations with Ireland and the reputation of its manufacturers.

Light armoured tactical vehicles

Key to purchasing decisions was to select a reliable platform that has already seen extensive service in the field, said Berry.

One example where this did not happen was the purchase of 27 “light armoured tactical vehicles” (LTAVs) from a South African company in 2009. The vehicles were recently retired after proving highly unpopular among Irish troops due to maintenance and reliability issues.

Figures released to The Irish Times show one such vehicle drove just 540km a year on average. The Defence Forces defended its record this week, calling it “a highly mobile and protected platform suited to modern peace support and security operations.”

Ireland was among the first countries to buy the vehicles. Berry says there are lessons to be learned here: “We can’t let ourselves be a guinea pig.”

However, some military sources express reservations about an over-reliance on France for military equipment.

“It is always a good idea to diversify your suppliers. If everything goes to hell in one country, you don’t want to be left with no spare parts or maintenance support,” says one officer.

The Government appeared to acknowledge this on Wednesday when Timmy Dooley, Minister of State at the Department of Agriculture, answered questions on behalf of Minister for Defence Helen McEntee in the Seanad.

“In light of ongoing geographical tensions and the lessons learned from Covid-19, supply chain resilience and security of supply have become increasingly important in the context of national security,” he said.

“With that in mind, the Minister will look to ensure an appropriate amount of diversification among suppliers to ensure a resilient, efficient and secure supply chain.”

Irish companies

Almost completely absent from the list of major military suppliers are Irish companies. This is to be expected, since Ireland has no traditional arms industry to speak of.

Reamda, a Kerry-based company, which makes bomb disposal robots for the Army’s Emergency Ordnance Disposal unit, is the only Irish manufacturer in the top 20. It received just under €2 million in payments in 2024 and 2025.

The Reamda Reacher at a demonstartion in Casement Aerodrome, Baldonnel. Photograph: Dara Mac Dónaill

The Reamda Reacher at a demonstartion in Casement Aerodrome, Baldonnel. Photograph: Dara Mac Dónaill

Some military sources expressed concern about the lack of military contracts being directed towards Irish companies.

“There is a national resilience issue here. It makes sense to direct at least parts of contracts to Irish companies to ensure reliability in supply, given global uncertainty,” says an Irish officer.

Unsurprisingly, this is also the view of the Irish Defence and Security Association (IDSA), a representative group for Irish companies involved in the defence sector. Members include drone, software and cyber defence companies, as well as big international arms manufacturers with representation in Ireland.

In a policy briefing note for Government officials, seen by The Irish Times, it argues for Irish “industrial participation” in defence contracts. The association pointed to examples of other EU countries which require national companies to receive a share of defence contracts.

In an Irish case, this could involve providing software or electrical parts as part of a larger purchase of military equipment from an international supplier.

It has called for a “comprehensive industrial participation policy in defence procurement” which would pave the way for Irish companies to contribute to national security.