Measuring the world precisely is much harder than it sounds. At very small scales, nature is noisy, and the rules of quantum physics make even the best instruments slightly uncertain. This limits how accurately scientists can measure things like electromagnetic fields, gravity, or time.

Now, a new study has shown that quantum entanglement can help overcome these limits in a completely new way. By linking atoms that sit in different places, the study authors have found a way to measure how physical quantities change across space with far greater precision.

This work turns a once-theoretical idea into a practical method that could improve some of the most precise measuring tools ever built.

“So far, no one has performed such a quantum measurement with spatially separated entangled atomic clouds, and the theoretical framework for such measurements was also still unclear,” Yifan Li, one of the study authors and a postdoc researcher at the University of Basel, said.

Dividing an entangled atomic cloud

The experiment starts with atoms cooled to extremely low temperatures, where quantum effects become dominant. Each of these atoms behaves like a tiny spinning magnet. The direction of this spin changes in response to electromagnetic fields, making it a sensitive probe of its surroundings.

Normally, when many atoms are measured independently, their random quantum fluctuations add up and limit accuracy. To get around this, physicists use entanglement, a quantum effect that ties particles together so that their behavior becomes correlated even when they are far apart.

In earlier experiments, entanglement had already been used to improve measurements, but only when all atoms were kept in the same place. This meant scientists could measure a single location very well, but not how a field changes from one position to another.

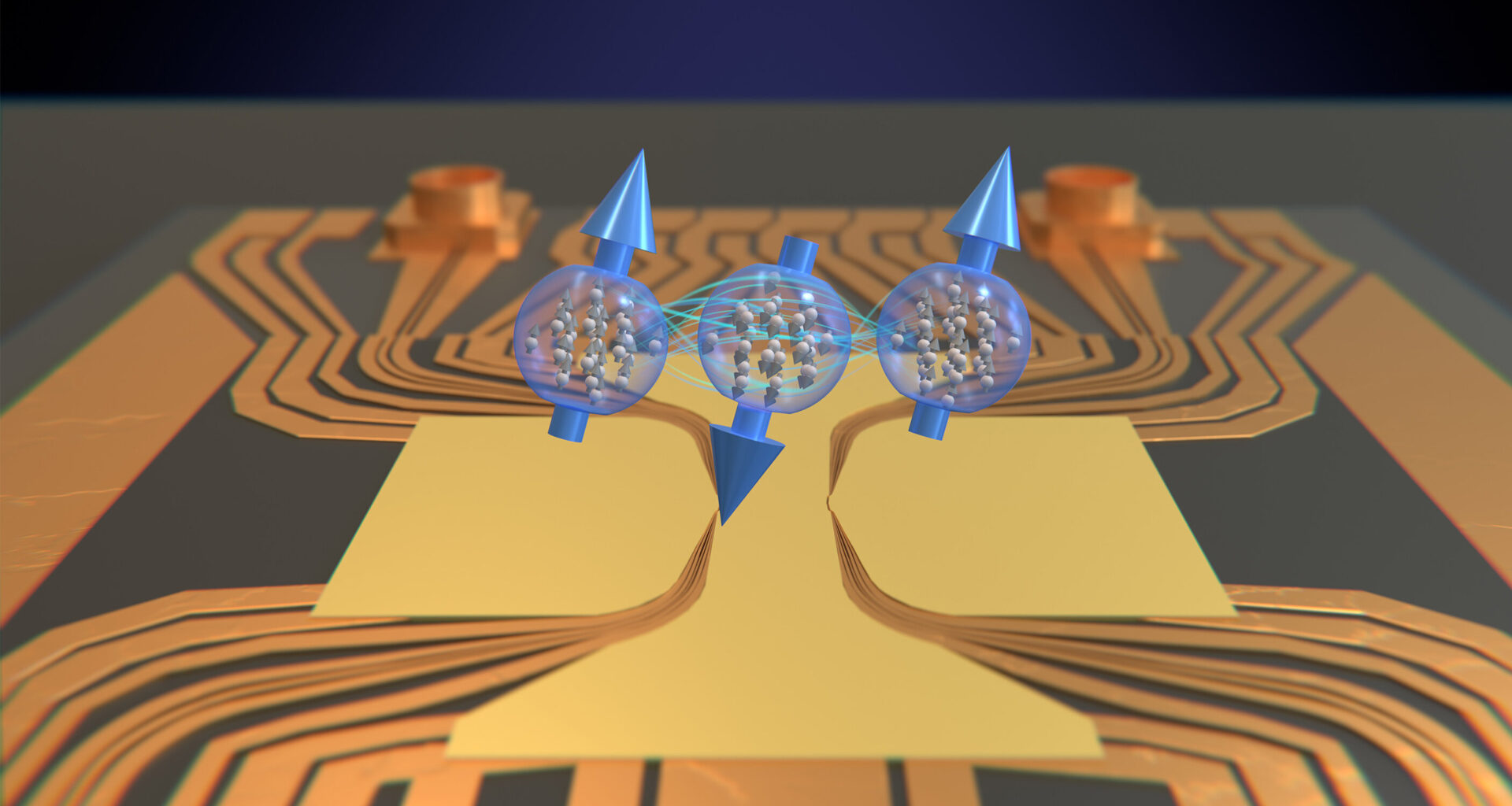

Separating entangled atoms without destroying their connection had remained an unsolved challenge, both experimentally and theoretically. The researchers solved this by changing the order of operations. Instead of separating atoms first, they began with a single cloud of ultracold atoms and entangled their spins while the atoms were still together.

Only after this quantum link was established did they divide the cloud into smaller parts, placing them in different locations. Surprisingly, the entanglement survived the separation. allowing the distant atomic clouds to continue behaving as parts of a single quantum system, reflecting the kind of long-distance correlations highlighted in the Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen (EPR) paradox.

“We have now extended this concept by distributing the atoms into up to three spatially separated clouds. As a result, the effects of entanglement act at a distance, just as in the EPR paradox,” Philipp Treutlein, one of the study authors and a professor at the University of Basel, said.

Each separated cloud sensed a slightly different portion of an electromagnetic field. By combining information from all locations, the researchers could determine how the field varied in space. Since the clouds were entangled, the usual quantum uncertainty was reduced, and disturbances that affected all atoms in the same way largely cancelled out.

The team also developed the missing theoretical framework needed to describe such measurements, showing how uncertainty can be minimized when multiple parameters are estimated at once using spatially distributed entanglement.

What’s the real-world use?

This work introduces a new kind of quantum sensor, one that is spread out in space but functions as a single, coordinated instrument. The technique can be directly applied to optical lattice clocks, which rely on large numbers of atoms arranged across space to keep time.

By reducing errors caused by variations in atom positions, these clocks could reach even higher levels of accuracy. The method is equally promising for atom-based gravimeters, where detecting how gravity changes across different locations is more important than measuring its average strength.

However, the proposed approach is technically demanding. Maintaining entanglement while splitting and controlling multiple atomic clouds requires extreme stability and precision, and extending the method to larger distances or more measurement points will not be easy.

The researchers now plan to refine their protocols and test them in real-world precision instruments.

The study is published in the journal Science.