Humpback whales (like these in the coastal waters of the Antarctic Peninsula) have long been observed creating rings of bubbles to corral prey. Credit: Whale Research Solutions.

Humpback whales (like these in the coastal waters of the Antarctic Peninsula) have long been observed creating rings of bubbles to corral prey. Credit: Whale Research Solutions.

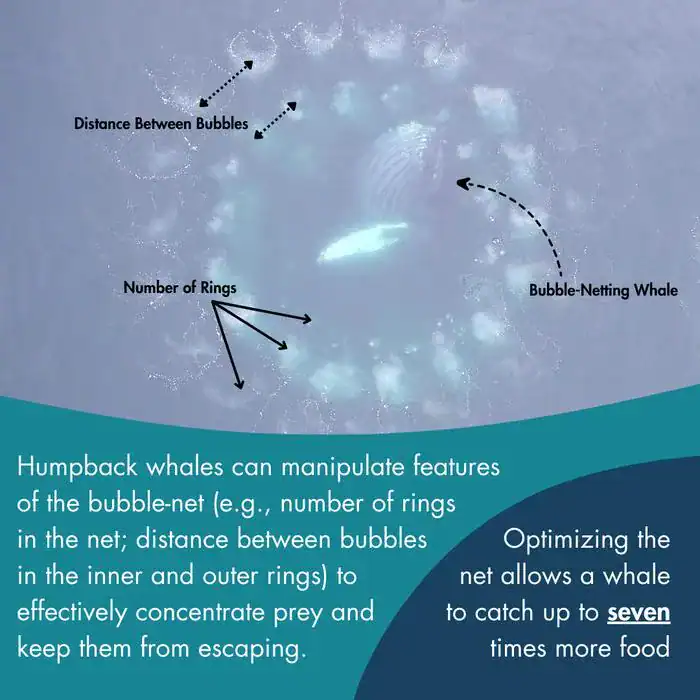

In the fjords of northern British Columbia, the ocean can look calm from the surface, but underneath, the action is just getting underway. A pale ring of bubbles rises on the formerly calm waters. Another follows. Seconds later, humpback whales burst upward through the middle, mouths open wide, pleats flared like accordion folds. Fish scatter too late. A successful trap has been set.

This hunting method is called bubble-net feeding, and a new study in Proceedings of the Royal Society B suggests it has been spreading through the humpback whale community in the Kitimat Fjord System over the past two decades. This is not just because individual whales “figure it out,” but because the behavior seems tied to who spends time with whom.

A 20-year whale “fingerprint” project

The researchers worked from 2004 to 2023, photographing whales and tracking individuals by the unique patterns on the undersides of their tail flukes. Over those two decades, they collected 7,485 photo-identifications across 4,053 encounters, identifying 526 individual humpbacks.

Nearly half of those whales — 254 individuals (48%) — were observed bubble-net feeding at least once, across 635 events. That’s a major part of how many whales in this fjord system eat. Bubble-net feeding can be done solo, but in this population, it was overwhelmingly cooperative.

The paper describes cooperative bubble-netting as more than a crowd of whales chasing the same prey. It involves coordination and likely different roles. While some whales laid the bubble curtain, others herded fish, and sometimes gave a distinctive low “feeding call” in the 400–600 Hz range. In this fjord system, Pacific herring was the only prey linked to cooperative bubble-net events.

If you’re a whale, learning this isn’t just about making bubbles. It’s also about timing, spacing, and reading the movements of your partners in dim water where you can’t rely on sight for long.

Do whales learn it from other whales?

Humpback whales at feeding time. Credit: Murray Foubister/ Wikimedia Commons.

Humpback whales at feeding time. Credit: Murray Foubister/ Wikimedia Commons.

To test whether bubble-net feeding spreads through social learning, the team employed a method known as network-based diffusion analysis. The idea is straightforward: if a new behavior moves through a population by learning from others, it should appear faster among individuals who spend more time with whales who already do it.

When the researchers used the overall social network, the signal was strong. Across their models, they estimated that roughly 55.6% to 59.9% of first-time bubble-net observations could be explained by social transmission.

×

Thank you! One more thing…

Please check your inbox and confirm your subscription.

The authors also point out a major complication, and it’s the kind of snag that comes up often when you try to study “culture” in wild animals.

Since bubble-net feeding in this population is usually cooperative, whales that feed like this will naturally spend more time with other bubble-net feeders. Similar individuals become more connected, not necessarily because learning flowed between them, but because the activity itself brings them together.

The ocean shifts, and the whales shift with it

The long-term record also shows a pattern around 2014. When the analysis focuses on well-sampled whales, the number of “non-bubble-netters” begins to decline after that point, which suggests whales already known to researchers later switched into the bubble-net category. The study notes that this timing overlaps with the 2014–2016 Northeast Pacific marine heatwave, a period tied to major ecosystem disruption and changes in prey.

The new study doesn’t claim the heatwave “caused” bubble-net feeding. But it raises a reasonable possibility: when prey starts to disappear, a population that can spread useful feeding tactics may be better able to cope.