Even as momentum builds toward sending humans to Mars in the next decade, several regions on the Red Planet remain off-limits to robotic exploration. The reason has nothing to do with distance or terrain. Instead, it reflects a long-standing international effort to prevent Earth microbes from contaminating potentially habitable zones.

Known as special regions, these areas could offer the best conditions for Mars life detection. No spacecraft, however, is currently authorized to explore them. The restriction stems from planetary protection guidelines that prioritize scientific integrity over operational ambition.

Recent data from NASA’s Perseverance rover in Jezero Crater has intensified the conversation. In 2025, the rover identified organic molecules in rock formations linked to water-rich environments, prompting renewed scrutiny of current exploration limits.

The Legal and Scientific Shield Around Mars’s Special Regions

Special regions are Martian locations where environmental conditions may support microbial life. These include areas with intermittent warmth or subsurface water. The Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) sets the criteria: any zone with temperatures above –28°C and water activity above 0.5 is flagged for protection.

The policy draws legal weight from Article IX of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which obligates nations to avoid biological contamination of other worlds. COSPAR’s planetary protection policy functions as the global implementation standard, informing mission protocols for agencies such as NASA, ESA, and CNSA.

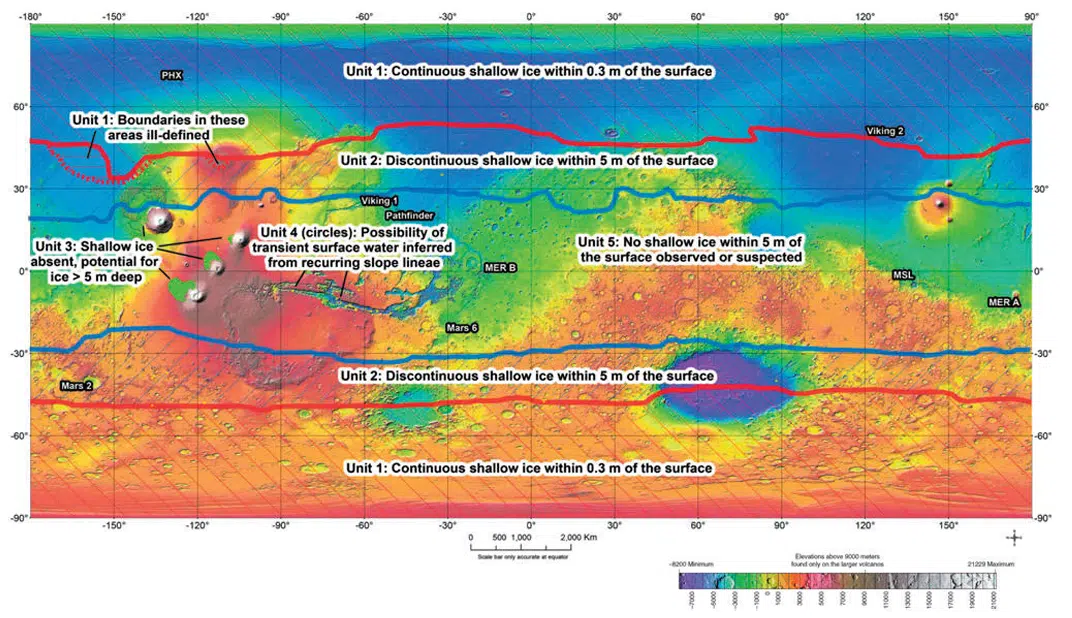

Map depicting geological features relevant to characterizing Special Regions on Mars. Indicated units describe shallow ground ice or potential transient surface water in terms of their depth below the surface and spatial continuity. Credit: National Academy of Sciences

Map depicting geological features relevant to characterizing Special Regions on Mars. Indicated units describe shallow ground ice or potential transient surface water in terms of their depth below the surface and spatial continuity. Credit: National Academy of Sciences

In a 2016 advisory, COSPAR extended caution to uncertain regions—zones suspected of meeting the microbial growth criteria. One example is recurring slope lineae (RSL), seasonal streaks on steep Martian slopes. Though once thought to signal liquid brine flows, more recent data suggest they may result from dry granular flows.

The National Academies of Sciences reinforced the need for strict controls in their 2021 review of the MEPAG Special Regions report. The panel emphasized that even minimal contamination could interfere with future searches for alien life and jeopardize critical Martian resources.

Scientists Divided Over Timing, Cost, and Contamination Risk

A 2017 paper in Astrobiology argued for softening restrictions. Led by Alberto Fairén, the authors proposed that robotic missions be allowed into potential special regions before human landings introduce unavoidable biological contamination. They cited rising mission costs as a key reason for policy reform.

That proposal met strong pushback. In a published response, JD Rummel and Catharine Conley—both former NASA planetary protection leads—stated that claims of unaffordable sterilization were exaggerated. Their analysis, available through PubMed Central, pointed to engineering assessments showing sterilization costs could increase total budgets by about 14 percent.

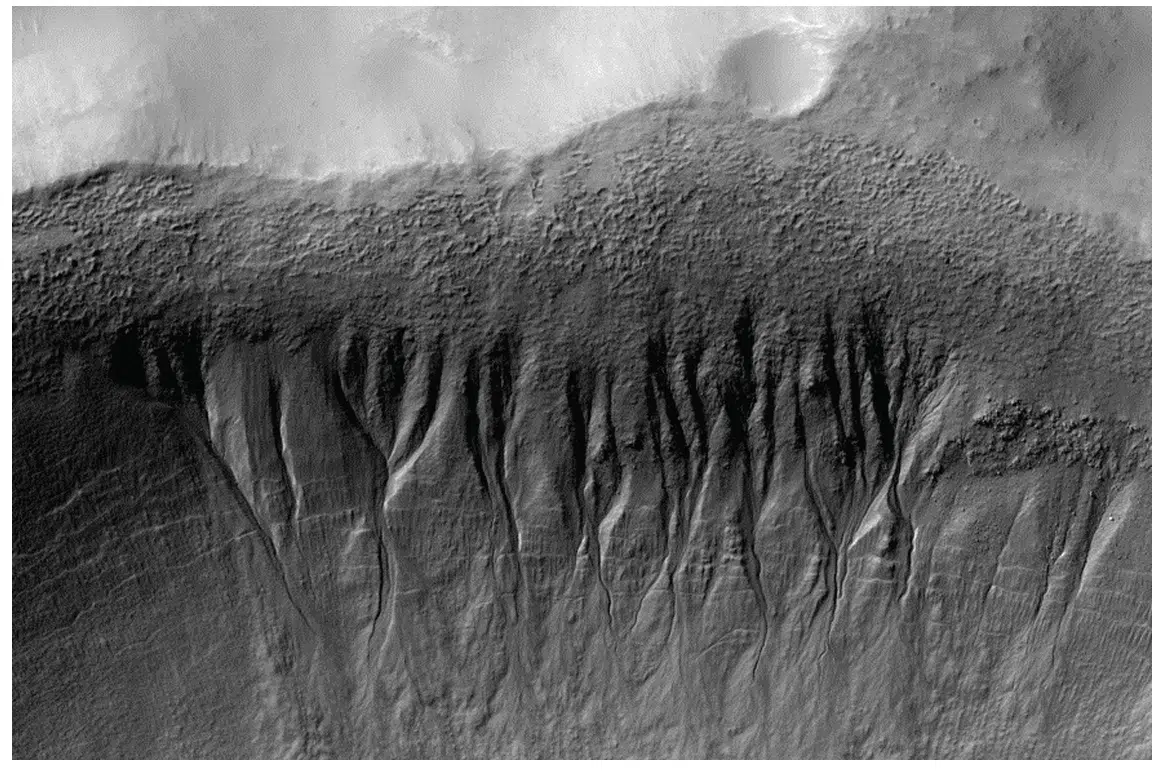

Mid-latitude martian gullies at 37.46°S, 222.95°E, exhibiting erosional alcoves, channels, and depositional aprons; all geological features that appear to be actively evolving and resemble landforms that on Earth are formed by water. Credit: National Academy of Sciences

Mid-latitude martian gullies at 37.46°S, 222.95°E, exhibiting erosional alcoves, channels, and depositional aprons; all geological features that appear to be actively evolving and resemble landforms that on Earth are formed by water. Credit: National Academy of Sciences

They also raised concerns about life detection credibility. Earth microbes newly discovered in extreme environments often display genetic traits that resemble those expected from hypothetical Martian organisms. Without full biosecurity, any discovery could be misinterpreted.

Additionally, they warned that contamination may not require a future astronaut. A rover operating on steep slopes, like those near RSL features, could fail structurally. A breach or crash involving a warm, contaminated power source might release Earth organisms into a previously sterile environment.

Terrain Limitations and Engineering Constraints Persist

Even in the absence of policy restrictions, physical access remains difficult. Many Mars special regions lie in hard-to-reach terrain. RSL form on slopes steeper than 45 degrees—well beyond current rover capabilities. Subsurface targets, such as possible brine aquifers, could sit more than 10 kilometers below the surface.

NASA’s Perseverance rover added urgency to the debate after its 2025 detection of complex organic molecules in the Bright Angel Formation, a layered rock sequence shaped by ancient water flows. While not direct evidence of life, the findings support the possibility that biologically significant environments still exist today.

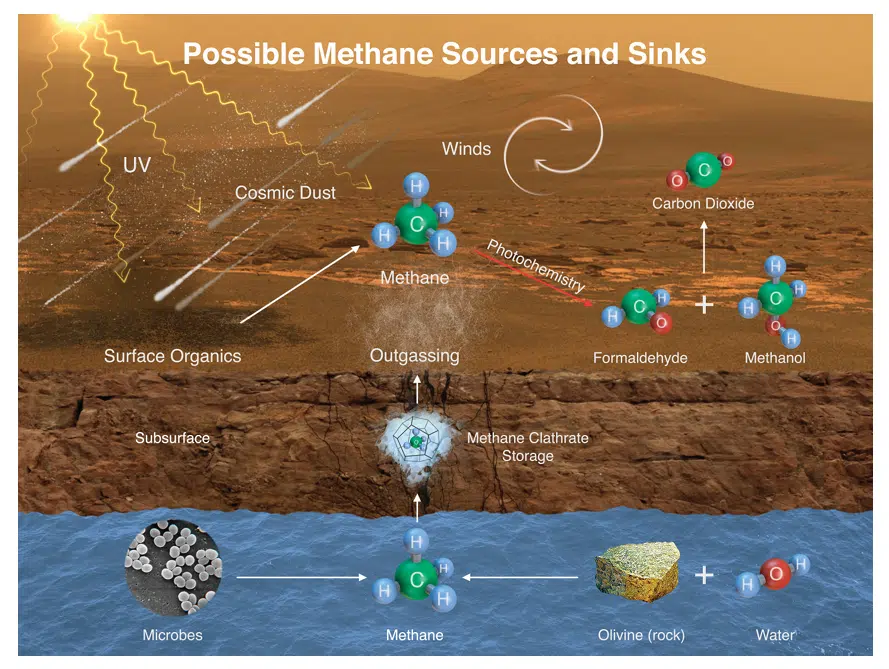

A schematic illustration of the known ways that methane (CH4) could be added to or removed from the atmosphere, processes known, respectively, as methane sources and sinks. Credit: National Academy of Sciences

A schematic illustration of the known ways that methane (CH4) could be added to or removed from the atmosphere, processes known, respectively, as methane sources and sinks. Credit: National Academy of Sciences

Under COSPAR’s most recent planetary protection guidelines, updated in 2023, all potential landing sites must be assessed for microbial risk. The policy incorporates hazard classifications, target environments, and biological load thresholds. Compliance is mandatory for all COSPAR-affiliated spacefaring nations.

Mars 2030 Crewed Missions Challenge the Planetary Rulebook

NASA and ESA’s Mars Sample Return campaign, set to begin launch stages later this decade, is under pressure to avoid protected zones. Samples must be collected from areas classified as safe, returned in sealed containment, and analyzed within biosafety-level facilities approved for extraterrestrial material.

Longer-term, the pressure will increase. Human missions—expected in the 2030s—will introduce an unavoidable microbial footprint. Many researchers argue this makes stricter protocols for current robotic missions even more important.

Rummel and Conley, in their formal critique hosted on PMC, warned that if robotic explorers contaminate habitable zones now, future scientists may lose the opportunity to identify truly Martian life. Once a region is biologically compromised, determining the origin of life signatures becomes significantly more difficult.

Other researchers have called for regulatory reform, citing evolving science, higher mission frequency, and the entry of private space actors. However, COSPAR’s role as the international coordinating body remains intact. The United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space reaffirmed COSPAR’s mandate in 2017.

At present, no robotic missions have been cleared to explore confirmed special regions. That could shift if terrain access improves or if new sensors identify brine-rich areas that meet the current threshold.