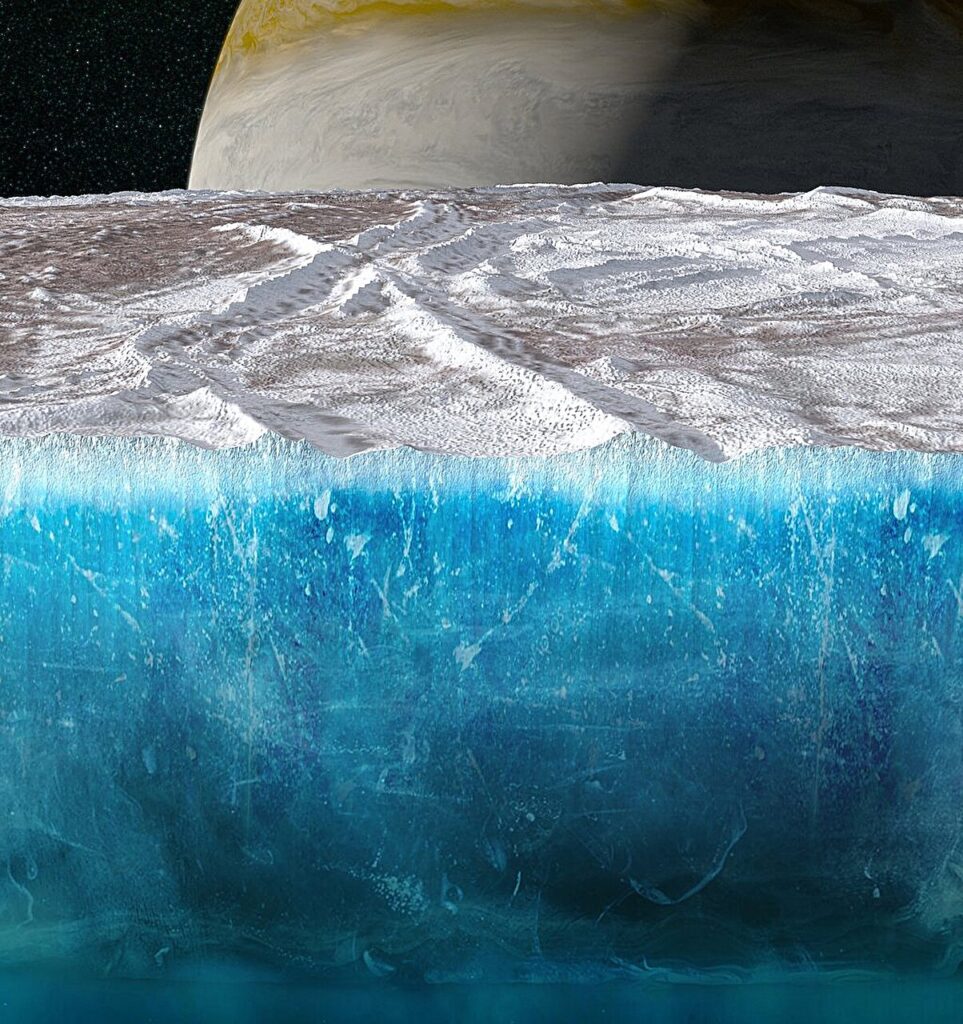

Artist’s concept of Europa’s ice shell. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Artist’s concept of Europa’s ice shell. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Europa has always been the Solar System’s most tantalizing “maybe.” This Jovian moon almost certainly hides a massive, salty ocean beneath its frozen exterior, which makes a prime candidate for life beyond Earth. But a nagging question remains: is the ice a thin, breathable skin or a massive, impenetrable wall?

New findings published in Nature Astronomy suggest the latter. By analyzing microwave data from NASA’s Juno spacecraft during its 2022 flyby, researchers estimate that Europa’s rigid outer ice shell is roughly 18 miles (29 kilometers) thick.

The 18-mile estimate relates to the cold, rigid, conductive outer-layer of a pure water ice shell,” said Steve Levin, Juno project scientist and co-investigator from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “If an inner, slightly warmer convective layer also exists, which is possible, the total ice shell thickness would be even greater.”

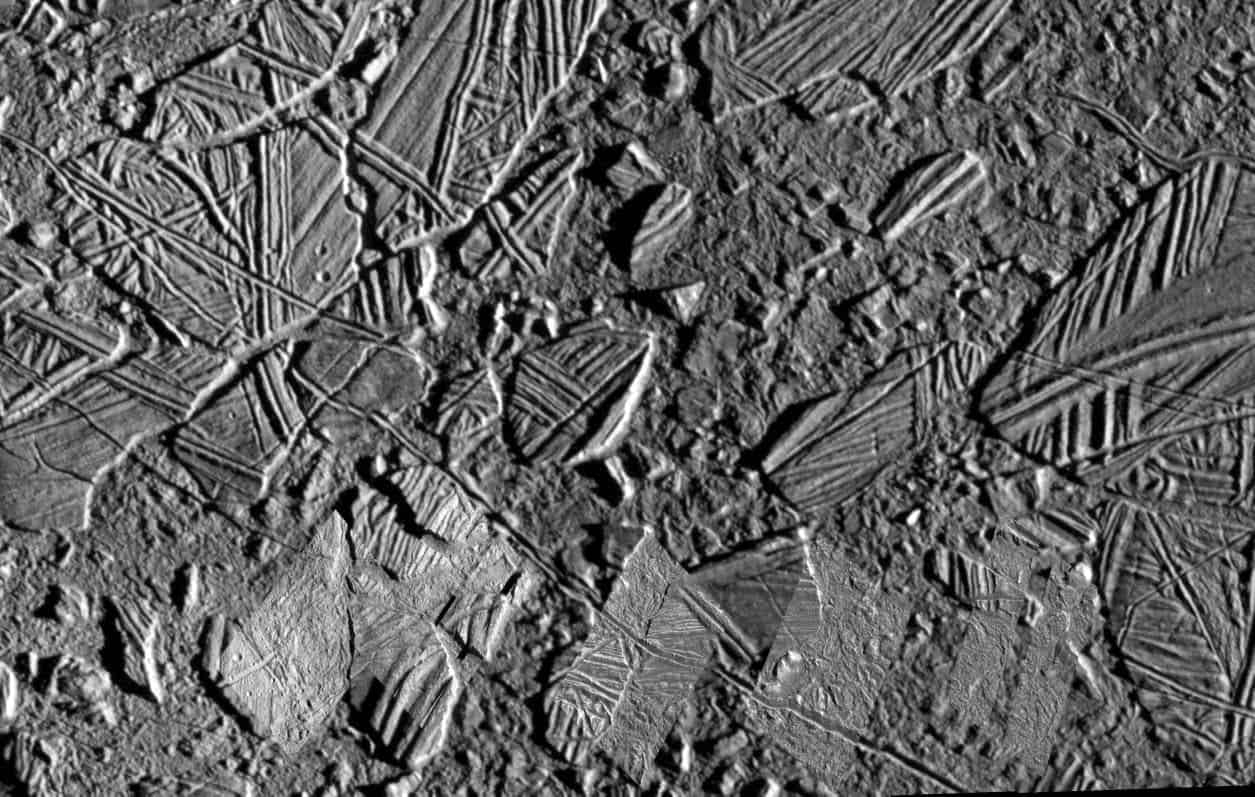

Peering Through the Frost

Juno was actually built to study Jupiter. However, its Microwave Radiometer (MWR) has a hidden talent. Because different microwave frequencies penetrate to different depths, the instrument acts like a remote thermometer for buried ice.

During the flyby, Juno came within about 220 miles (360 kilometers) of Europa’s surface, and MWR gathered data across six frequency bands. Higher-frequency microwaves tend to sample shallower layers, while lower-frequency microwaves can probe deeper. By tracking how Europa’s microwave “brightness temperature” changes across those channels, the team could test different ice-shell setups — thin, thick, clean ice, saltier ice, and so on.

The conclusion was that the ocean surface had a pretty thick shell, even if the salinity is less than expected.

“If the ice shell contains a modest amount of dissolved salt, as suggested by some models, then our estimate of the shell thickness would be reduced by about three miles,” Levin said.

Why Thickness Matters

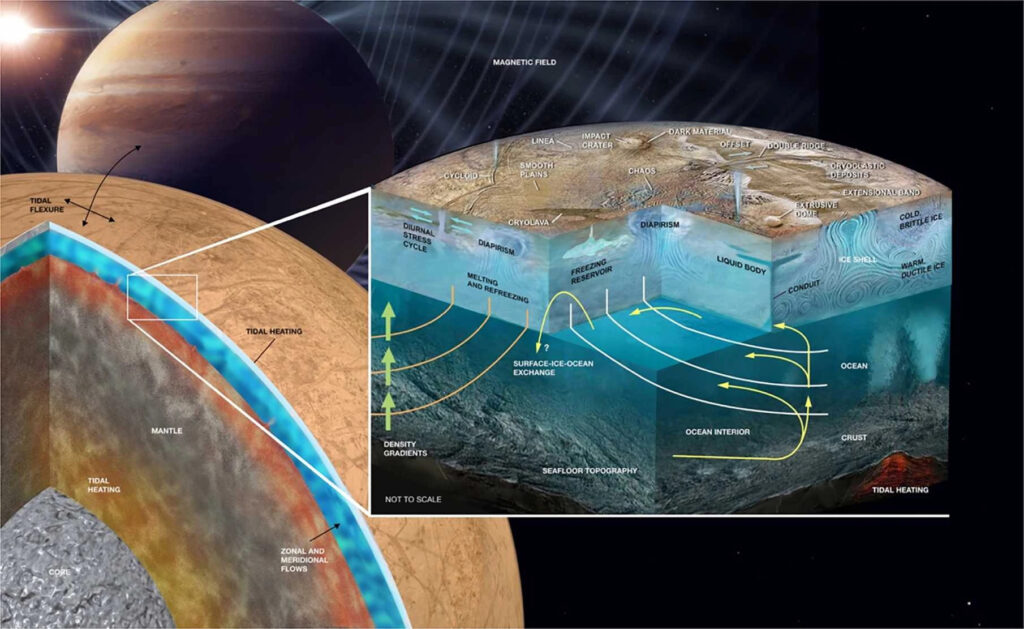

Depiction of processes inside Europa’s ocean. Image via Wiki Commons.

Depiction of processes inside Europa’s ocean. Image via Wiki Commons.

Liquid water is necessary for life as we know it, but it’s not the only necessity.

×

Thank you! One more thing…

Please check your inbox and confirm your subscription.

A thin shell acts like a porous filter, allowing surface chemicals to cycle down easily. A thick shell, however, suggests a “tough lid” that makes this chemical exchange much harder. It doesn’t rule out life, but it suggests that the “breathing” process might be limited to rare, violent events like meteor impacts or localized melting.

It also matters for future missions. A thick, cold outer shell behaves differently than a thin one when it comes to cracking, heating, and recycling surface material. That changes what instruments should look for, and where they should look.

NASA’s Europa Clipper is built for dozens of repeated flybys aimed at measuring the ice shell, the ocean, and how material may move between them. The Clipper is expected to reach Jupiter in April 2030. The ESA’s JUICE mission is also headed to the Jovian system, with arrival expected a year later. The two missions are expected to complement each other with coordinated observations. Knowing what to expect could help researchers tweak the mission accordingly.

Life on Europa?

For now, Juno’s microwave scan tightens the debate: Europa’s ice, at least in the area Juno measured, looks thick enough that the most obvious cracks and pores probably don’t connect straight down to the ocean.

That may sound like a letdown. But in planetary science, knowing what doesn’t work is often as helpful as knowing what might. If Europa’s ocean is habitable, it may depend less on simple surface fractures and more on deeper, rarer processes that Europa Clipper and JUICE will be built to chase.

Life on Europa might not be easy to find, but it’s definitely not ruled out. We’re just realizing that this moon is less of a “frozen pond” and more of a complex, churning engine.