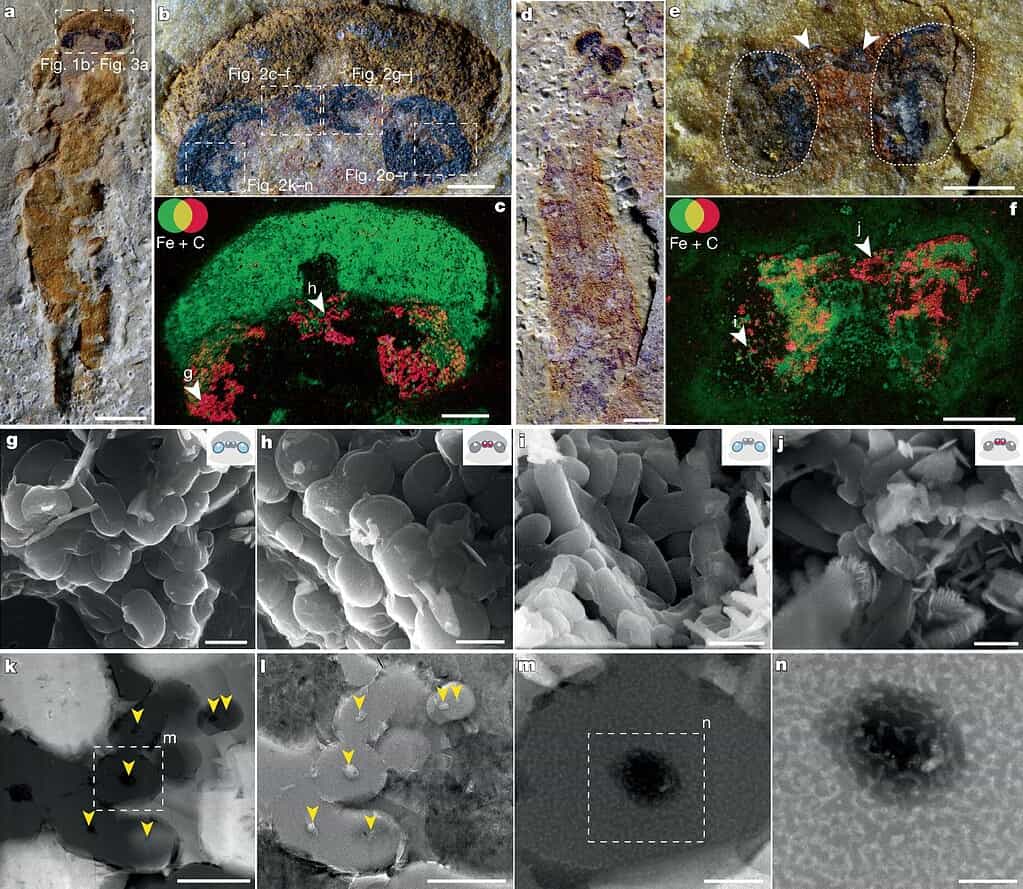

General morphology of the lateral eyes and pineal complex with their preserved melanosomes in two species of Myllokunmingidae from the Chengjiang biota. Credit: Nature (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09966-0.

General morphology of the lateral eyes and pineal complex with their preserved melanosomes in two species of Myllokunmingidae from the Chengjiang biota. Credit: Nature (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09966-0.

Every mammal, every fish, every vertebrate (creatures that have a spine) has two eyes. It’s been that way for millions and millions of years. But maybe it wasn’t like that forever.

During the Cambrian, when evolution was experimenting all sorts of strategies, early vertebrates may have had four eyes, and they were high-res eyes, too.

The Original Four-eyes

In a study published in Nature, researchers analyzed rare specimens of myllokunmingids, the most primitive known vertebrates from the Cambrian Period. These were essentially jawless prehistoric fish, early experiments in what would become a giant biological group.

At the time, the oceans were a “Dark Forest,” a term the researchers use to describe a cutthroat arena where the first great arms race of life was in full swing. You had fierce, meter-long apex predators like the radiodonts, equipped with terrifying claws and complex compound eyes. Meanwhile, the myllokunmingids were small, soft-bodied, and presumably delicious.

To survive, they needed an advantage. This advantage may have have come in the form of great vision.

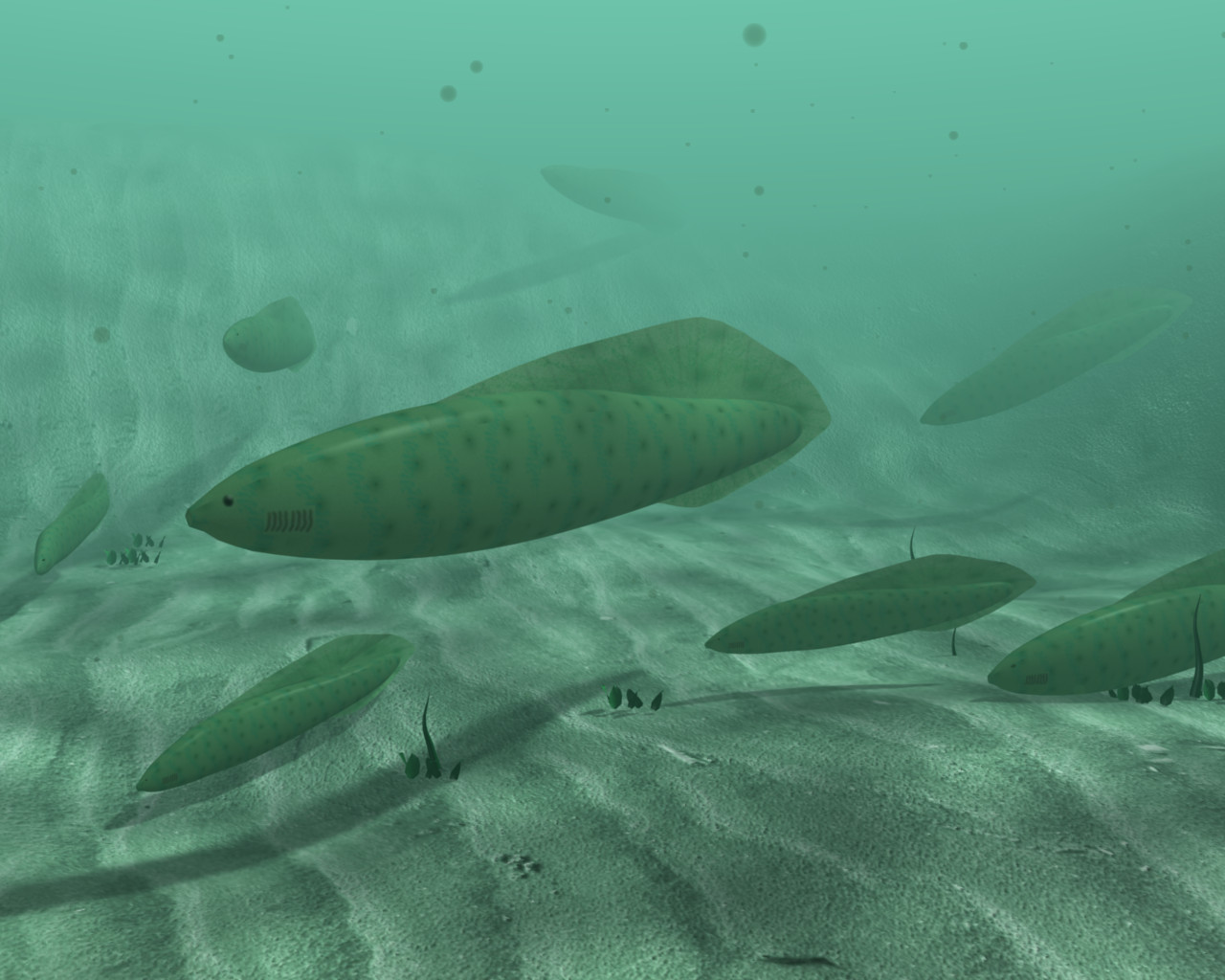

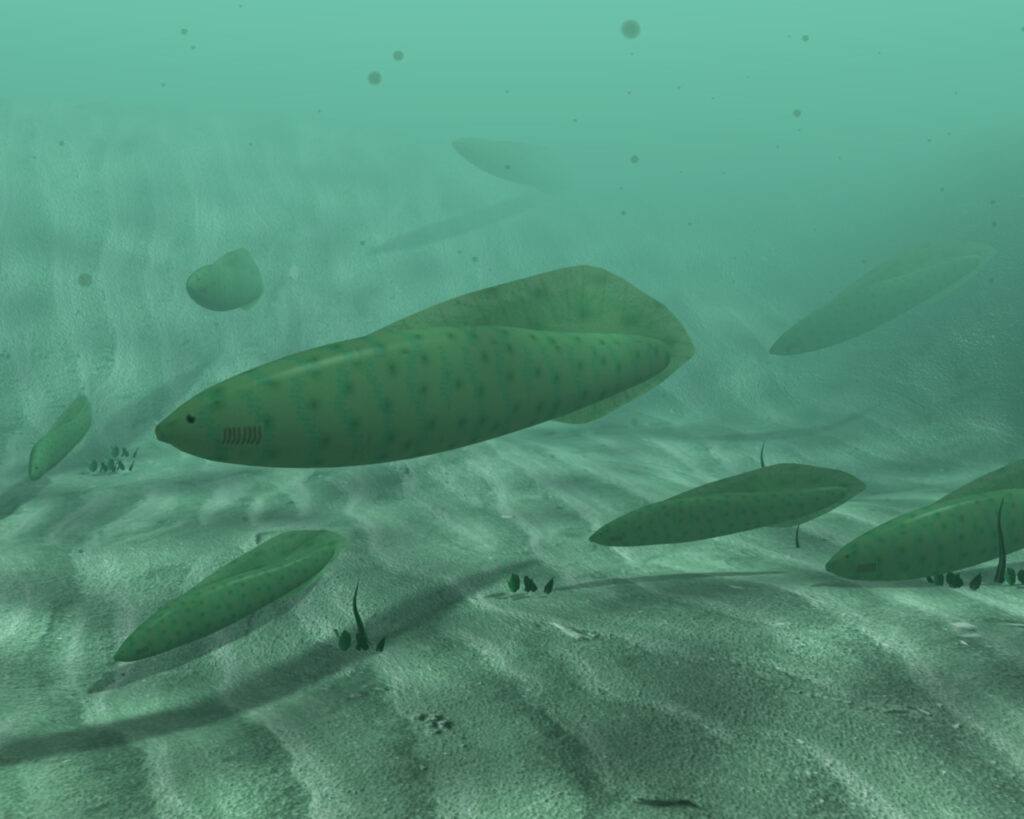

Artistic reconstruction of Myllokunmingiidae. Image via Wiki Commons.

Artistic reconstruction of Myllokunmingiidae. Image via Wiki Commons.

Researchers reexamined fossils of Haikouichthys ercaicunensis and an unnamed myllokunmingid species, the team identified two “median” spots between the traditional lateral eyes. For years, these spots were dismissed as nasal sacs. But on closer inspection (with scanning electron microscopy and elemental mapping), the “noses” started to look suspiciously like high-end optics.

The structures contained melanosomes, which are tiny, carbon-rich packages of pigment identical to those found in the retinas of modern vertebrates. Even more shocking was the presence of a “distinctive, regularly ovoid structure” in both the lateral and median eyes. In other words: a lens.

“We interpret this ovoid structure as an eye lens on the basis of its shape, size and position. This lens structure also occurs in the median paired dark spots,” the authors explain in the study.

A camera-type eye is a highly-performant type of eye that uses a lens to focus light onto a hemispherical retina, creating a clear image rather than just a vague sense of light. Finding this setup in a pair of lateral eyes is expected, but finding it in a second dorsal (back) pair is stunning. It suggests that the very first vertebrates may have had a 360-degree vision system.

×

Thank you! One more thing…

Please check your inbox and confirm your subscription.

From Four Eyes to a Pineal Gland

If our ancestors had four eyes, this begs two questions; first, why did evolution give up on that, and second, where did the pair of eyes go?

There are several reasons why two eyes might be better than four. The first is the “processing power” required for this type of acute vision. Maintaining four high-resolution streams of data would have required significant neural real estate and caloric intake — a luxury for an animal. Then, researchers suspect the animal may have become a bit of a predator itself. This selective pressure of spending more time hunting (and less time being hunted) reduced the need for a 360-vision system.

But it gets even more intriguing: researchers suspect that the second pair of eyes may have morphed into what we now call the pineal gland.

The pineal gland is a small endocrine gland in the brain of most vertebrates. It produces melatonin, a serotonin-derived hormone, which modulates sleep patterns following the diurnal cycles. In some animals, this gland has been linked to a light-sensing organ sometimes referred to as “the third eye.”

This study offers support for that idea. In fact, this study suggests that this “third eye” didn’t start as a single, degenerate light-sensor, but rather as a fully functional pair of camera eyes.

As we sit here today with our two eyes, reading this on a screen, the study is a reminder that we’re the streamlined remnants of a much flashier past that started in the Cambrian. We are the descendants of a little fish that saw the world in a way we can barely imagine.

Journal Reference: Xiangtong Lei et al, Four camera-type eyes in the earliest vertebrates from the Cambrian Period, Nature (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09966-0