Researchers have shown that a satellite’s onboard data can flag a debris strike, even when trackers never saw it.

Those fingerprints can turn mysterious failures into documented events and improve forecasts that guide how operators protect billion-dollar hardware.

Satellite teams watch for sudden changes in pointing, power, or temperature, because small jolts can cascade into bigger problems.

Anne Aryadne Bennett at the University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder) studied those jolts in detail.

At CU Boulder, her work tracked how onboard computers correct a hit, and how that correction itself becomes evidence.

That evidence matters because operators need fast answers when a spacecraft drifts, and insurance clocks start ticking.

Control systems leave clues

Every working satellite streams status data to the ground, and that stream can capture the instant after a collision.

Engineers call this stream telemetry. It consists of simple health and pointing numbers, and Bennett’s CU Boulder team mined it for abrupt jumps.

When a hit nudges the craft, its control software fires thrusters or spins wheels to push it back on target.

Telemetry can miss a strike that leaves no visible wobble, so teams still rely on engineering judgment and outside tracking.

Why tiny impacts cripple

Most strike threats come from fragments too small to track, and they can slam into hardware at extreme speed.

In hypervelocity impacts – collisions faster than sound in materials – a particle creates a shock that cracks and spalls panels.

A hit can also spray secondary fragments inside, because the impact turns both particle and wall into fast shrapnel.

The impact research team at Johnson Space Center logged many spacecraft impacts, but operators still balance shielding against mass and power limits.

Transfer orbits raise risk

After launch, many communications satellites spend weeks climbing toward their working slot, using engine burns to raise the orbit.

The goal is geostationary orbit, where satellites match Earth’s spin and stay over one longitude, so antennas keep a steady aim.

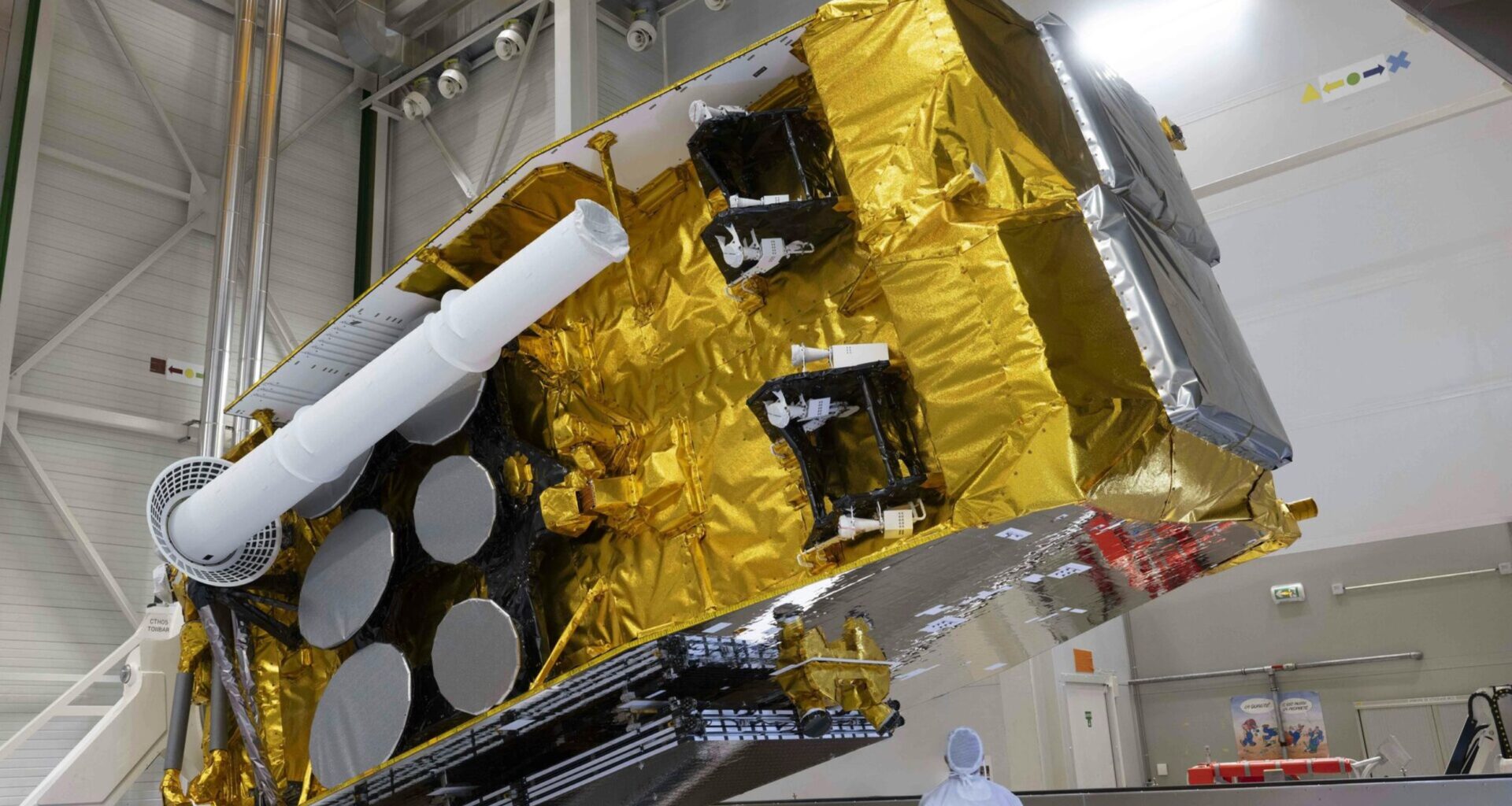

Late last year, Spain’s newest military communications satellite, SpainSat NG-2, suffered a particle strike while traveling to its final position in space.

At those heights, tracking gaps grow and a jolt can leave teams with only onboard evidence to interpret.

A satellite struck en route

Indra Group, the majority owner of Hisdesat, the Spanish company that operates the country’s military communications satellites, later confirmed the particle strike in a notice to investors.

The document said the satellite kept working, and teams would only start a replacement if damage reached critical areas.

The company described its response to the incident in the filing.

“Hisdesat implemented a contingency plan to ensure that the Ministry of Defense and other clients are not affected. The technical team is analyzing the available data to determine the extent of the damage,” Indra Group said.

Networks designed for failure

Military satellite networks rarely rely on a single spacecraft, because commanders expect connections to survive hardware trouble.

When one node weakens, controllers can move traffic to another satellite, because ground modems rekey and retune radios.

Operators also keep spare ground hardware and keys ready, because encrypted links fail if one missing setting blocks authorization.

Such plans prevent sudden blackouts, but they can limit coverage or data rates while the network runs without full capacity.

Blind spots in debris detection

After an impact, operators often cannot tell whether the culprit was natural dust or debris from human activity, because both move fast.

Tracking networks follow only the largest pieces, so orbital debris, broken hardware from past missions, stays mostly anonymous at small sizes.

Bennett’s study compared several detection approaches, and it found that some held up when control corrections muffled the signal.

That gap means the phrase space particle often reflects missing information, not a mystery substance with special behavior.

Designing against surprise hits

Engineers design critical spacecraft areas to take damage and keep working, because impacts rarely hit a convenient, empty spot.

Designers add spaced layers of metal and fabric, so the first layer breaks the particle and the next layer catches spray.

They also separate wiring and fuel lines, because a puncture in one bay should not cascade into a full system failure.

Even with hardening, a strike on a vital area can still end a mission, and that risk drives insurance and replacements.

Turning strikes into standards

When operators can confirm a strike, they can feed that event back into hazard models, rather than writing it off.

Bennett’s work treated satellites as accidental sensors, because each recorded jolt carries clues about size, speed, and direction.

Better strike records help engineers tune shielding requirements and help regulators judge whether new satellite fleets add unacceptable debris risk.

Military operators may share little detail for security reasons, so scientists still face blind spots in the highest-value orbits.

What comes after the hit

The SpainSat incident shows how a single unseen particle can test both spacecraft design and the ways we interpret onboard data.

As operators adopt telemetry-based detection and planners tighten debris controls, real resilience will still depend on redundancy and time.

Photo: Airbus Defence and Space

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–