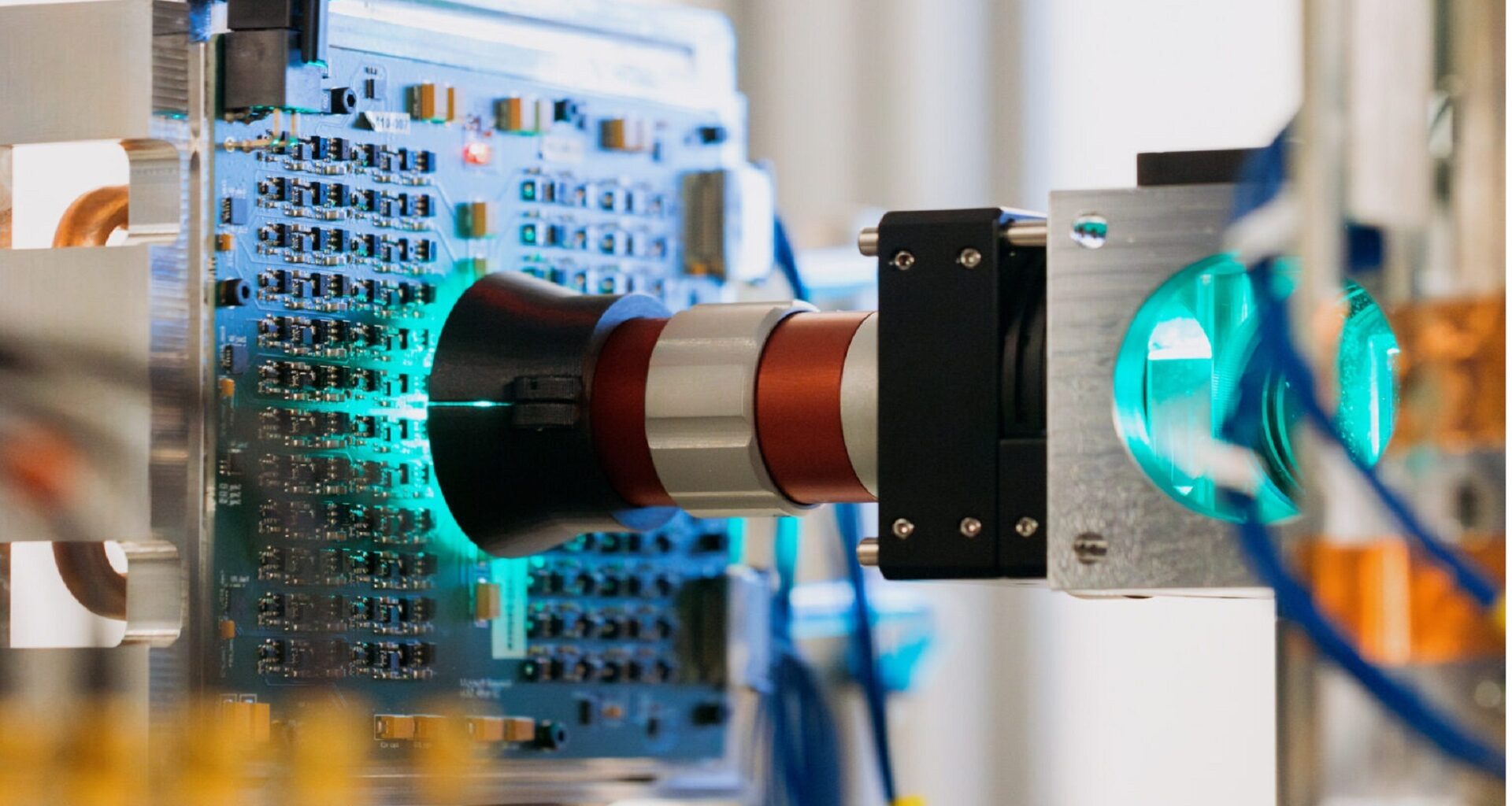

Microsoft Research has built a prototype computer that doesn’t rely on electrons zipping through silicon but on beams of light.

The machine, called an analog optical computer (AOC), is designed to solve complex optimization problems and could one day handle artificial intelligence workloads with far greater speed and efficiency than today’s processors.

Unlike digital computers that crunch information in binary, the AOC embodies computations in physical systems. This avoids bottlenecks that slow down conventional chips and could make the system 100 times faster and more energy-efficient at specific tasks.

The prototype is built using commercially available parts, including micro-LED lights, optical lenses, and sensors from smartphone cameras, keeping costs down and making future mass production feasible.

The team also developed a “digital twin,” a software version of the AOC that mimics the way the hardware behaves.

This allows researchers to test the system at scale, explore how optimization or AI problems would map onto the hardware, and share results with outside collaborators.

“To have the kind of success we are dreaming about, we need other researchers to be experimenting and thinking about how this hardware can be used,” said Francesca Parmigiani, who leads the project at Microsoft Research Cambridge.

Cracking real-world problems

One of the first demonstrations involved finance. Microsoft worked with Barclays Bank to test how the AOC could optimize delivery-versus-payment securities transactions, a process used by clearinghouses to settle trades between banks.

The experimental setup handled thousands of transactions among up to 1,800 parties, just a fraction of the scale in real clearinghouses but enough to show how future versions of the hardware could make a difference.

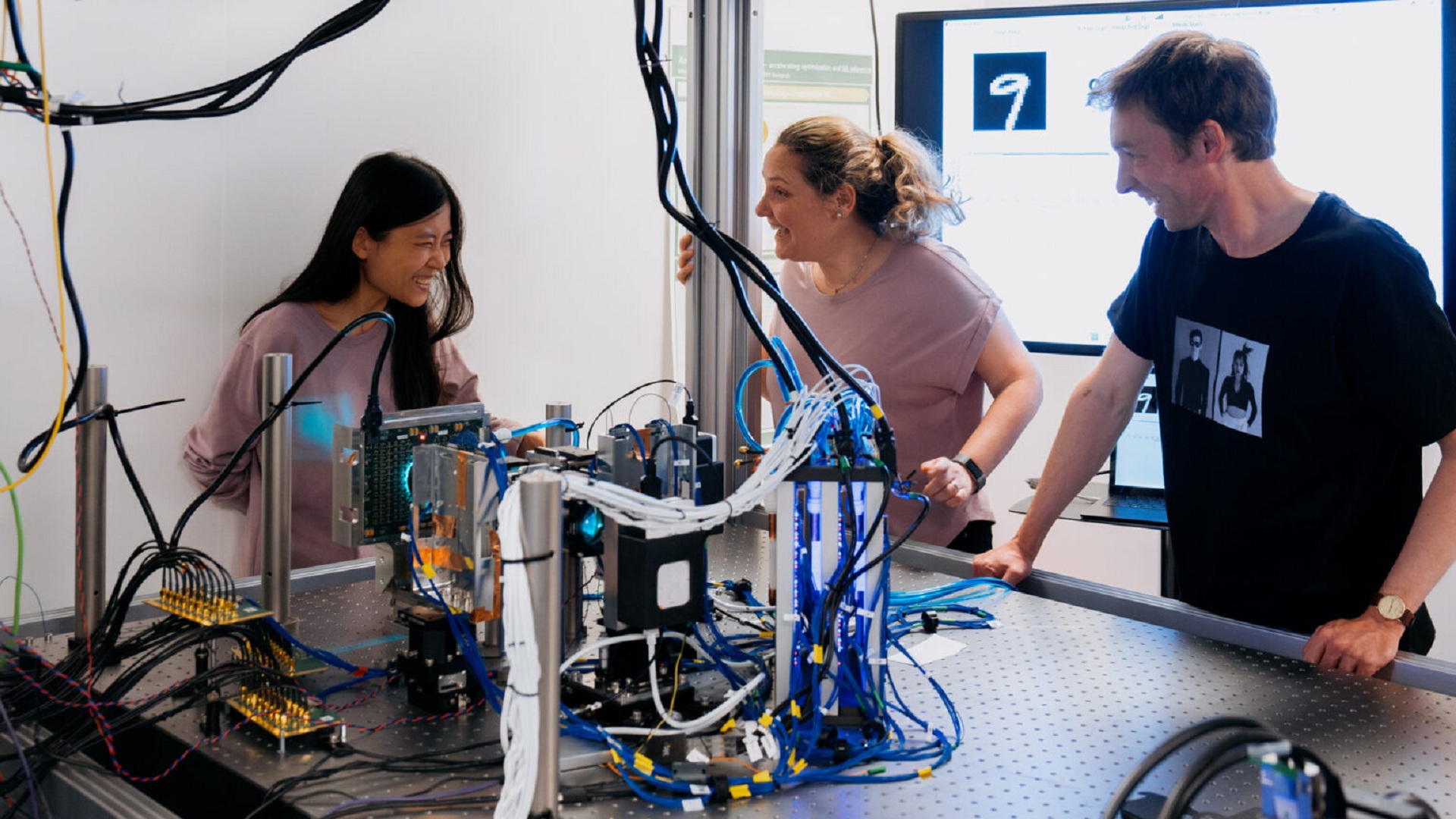

Researcher with the current model of Microsoft Research’s analog optical computer. Credit-Chris Welsch/Microsoft.

Researcher with the current model of Microsoft Research’s analog optical computer. Credit-Chris Welsch/Microsoft.

“It is an absolute giant problem with massive real-world finance impact,” said Hitesh Ballani, who directs research on future AI infrastructure at Microsoft Research.

Healthcare offered another proof-point. Using the AOC’s digital twin, researchers reconstructed MRI scans with promising accuracy. Today, a typical scan takes about 30 minutes; the optical system could theoretically cut that to just five.

While not yet ready for clinical use, the experiment hints at how the technology might reduce waiting times and improve access to diagnostics.

Michael Hansen, a senior director at Microsoft Health Futures, noted that the digital twin was crucial in showing the viability of larger-scale MRI reconstructions.

A future with AI

The Cambridge team also sees potential for running AI workloads. Current large language models require enormous energy to process billions of parameters, but the optical approach could handle reasoning tasks like “state tracking” far more efficiently.

“The most important aspect the AOC delivers is that we estimate around a hundred times improvement in energy efficiency,” said Microsoft researcher Jannes Gladrow.

The prototype currently manages just 256 parameters, but researchers believe it could scale to millions or even billions as micro-LED components are miniaturized.

For Ballani, the long-term vision is clear: “Our goal is this being a significant part of the future of computing, with Microsoft and the industry continuing this compute-based transformation of society in a sustainable fashion.”

The findings of the study have been published in the journal Nature.