Read all of Slate’s stories about the 25 Greatest Picture Books of the Past 25 Years.

Sophie Blackall is into history: the stories you find in it, the visuals you get from it, the emotions it makes you feel. Farmhouse, which appears on Slate’s list of the 25 best picture books of the past 25 years, incorporates items Blackall found in an abandoned house on a property she purchased in upstate New York. Blackall ambitiously imagines the structure’s previous life as a family home, then chronicles nature’s reclamation process after the very last child has left and the house is inhabited by squirrels and a hibernating bear.

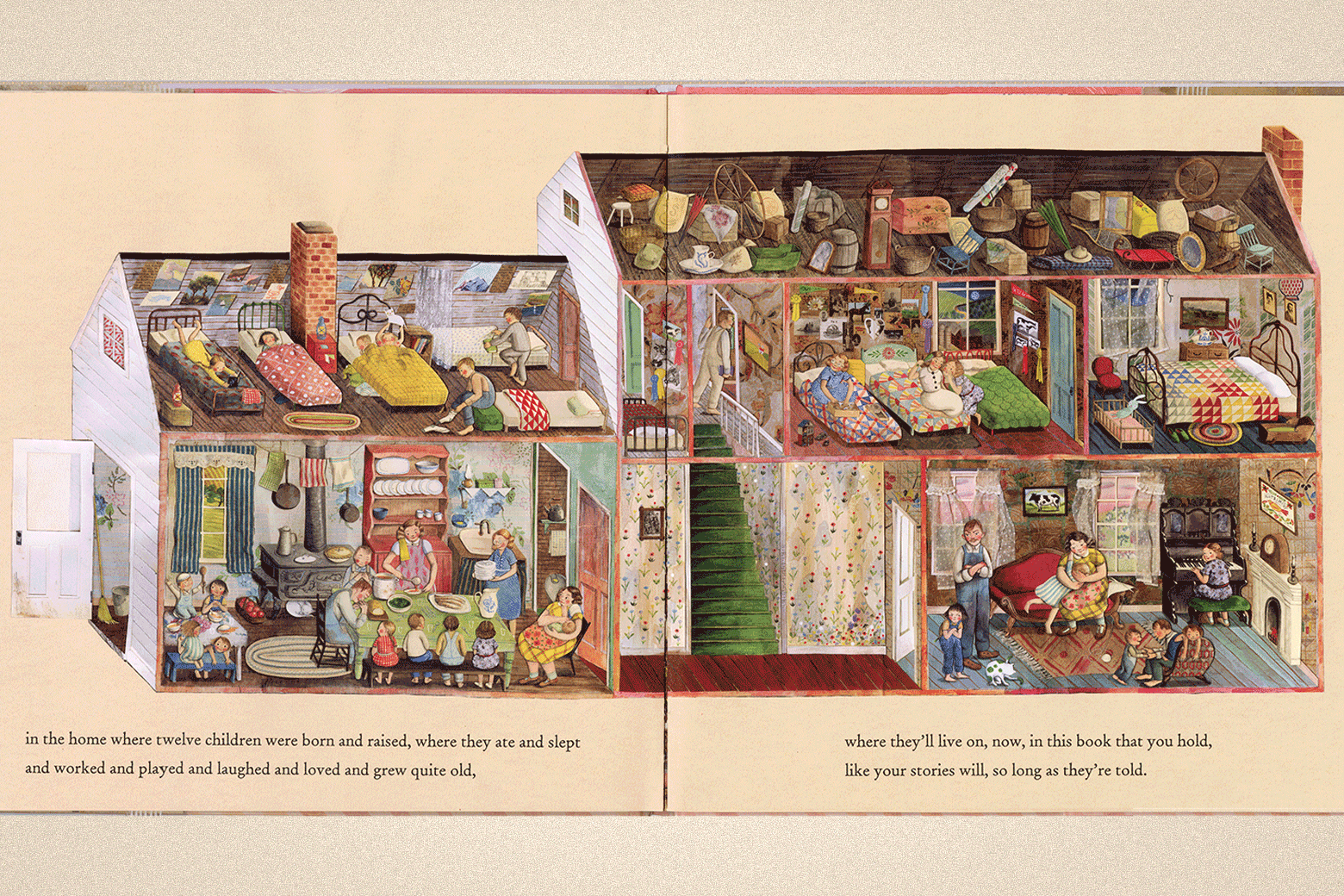

In a last-act twist, Blackall reveals that this is a real house, discovered by the very woman who wrote this book you hold in your hands. Farmhouse ends with a final cutaway spread of the whole house, as it was when the family lived in it, decades ago. I talked to Blackall about that final, beautiful page, why she ended the book that way, and how children respond to it. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Rebecca Onion: Why do you like to use a cutaway, maybe especially at the end of this book?

Sophie Blackall: As I walked through the actual physical falling-down house, I realized that there was all of this evidence of the passing of time. And as I went from room to room, I started to build this sense of who this family was and the fact that there had been 12 children. And as I was literally looking at their belongings, their schoolbooks, and so on, like a detective, I was piecing together the history of this family and their lives. And, at the same time, the peeling wallpaper was this evidence of generations. There were lives before that.

Sometimes I think quite cinematically about a book and the experience of reading a book. And in an age where children are bombarded with digital technology constantly, for a physical book to compete for their attention, it has to be a compelling and beautiful and engaging physical object that invites them to step into it, almost, and to immerse themselves in it, and to turn the page. Everything I do is geared towards getting a child to turn the page.

So the idea came about, as I was walking through this house, that the pictures would build to this cutaway of the entire house, and that we would see, piece by piece by piece, these fragments of a life, built out of the actual physical fragments of what was left behind in the house—the fabric, the wallpaper, the schoolbooks, the newspapers—and that these pages would bleed into each other, that one story ran into the next, the way our lives do. And so from one page, you will see the edge of the next room, and it’s this invitation to turn the page, to step into the adjacent room. It’s all overlapping. Time overlaps, and the great web of our connections overlap, and our stories overlap.

By the end, the youngest sibling, who is now quite old, is leaving the house. We’ve gone in this little circle from room to room. And then the big cutaway at the end is where we step back and we see what’s gone before.

Yes! It’s just like at the end of a movie, where you see a montage that flashes back to things that have happened in the movie. When you turn the page and get to this whole-house cutaway, you see little scenes in each room that recapitulate what happened earlier in the book. Looking at it, you remember how funny the clowning little kids at the kids’ table were, the cat they painted green, the apples in the bushel in the kitchen, which recall the beautiful spread of the kids in the big apple tree.

Then there’s this bonus, a new image—the attic full of objects. We haven’t seen that earlier.

Photo courtesy of Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

That’s right, and the parents’ bedroom you also don’t see previously. I put two portraits hanging on the wall in the parents’ room, and those were the actual parents of the family, the Swantaks. The youngest son of the youngest son is still alive. He’s in his 80s and he still lives in the valley, and he shared some family photos with me.

Were the objects in the attic things that you found in the house?

Some of them are, and some of them were things we found in the barn. We live in a farmhouse from 1790 that’s 15 minutes away from this one, and there were things that came in that attic that I put in here—so it’s an amalgam of attics.

Another new thing in this last spread is the teenage brother’s narrow little room, the only single room any of the kids have.

Oh, yes, just at the top of the stairs. I did take some liberties, because I had to sort of figure out who would have slept in which bedroom with whom. But I was talking to another older farmer around here, who grew up in a big family, and he said when he went away to join the Army, it was the first time he had a pillow to himself. He shared a bed, as a teenager, with three of his sisters.

Dan Kois

The Instant-Classic Picture Book That Forced Even the Most Serious Adults to Get Silly

Read More

That’s the kind of thing where, if you were to put it in a book like this, the kids would have so many questions. This cutaway appears on the physical cover of the book too, under the dust jacket.

That was really a fun eleventh-hour idea. I love seeing kids pick up the book and run their hands over the embossed windows on the jacket. We did everything we could to try and make it feel like these are windows. They’re shiny, and you can feel them with your fingers. And then if you take the jacket off, you see the rest of the house. Seeing kids do that thing, of hugging a book to their chest, with this one, it’s very satisfying.

Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

Somebody sent me a message, some stranger on Instagram, saying their 2-year-old said, “I want to go in that house, Mama.” And I thought, Oh, that’s it. That’s what it’s all about. Open that book. Let me into that book. Let me into that story. Let me into that house.

I read Farmhouse with my 9-year-old niece. And she kind of had this intake of breath when we turned the pages and saw the parts where the house was abandoned, and she was like, “They just left their house?” She thought it was very sad. Then, when we closed the book, she looked at me and said: “That was a GREAT book.”

Yeah, I have done a lot of school visits with this book. When I get to the end, the kids are all kind of misty-eyed, and they say, “Is the house still there?” And I say, “No, it’s quite sad that it fell down, but I have this book, and this story, and that’s what this is about: It’s about saving stories, out of things that are gone.”

And then I take a breath and I say, “Do you want to see the bulldozer come and crunch it up and shove it into the ground? I have a video.” And of course they want to, because what is more thrilling? They go immediately from “Oh, this is so sad” to “Show me the bulldozer smashing this house to bits!”

Because they’re kids; that’s how they are. Those two things can coexist, which is why children are so brilliant.

Get the best of movies, TV, books, music, and more.