Subscribe to our newsletter

Success! Your account was created and you’re signed in.

Please visit My Account to verify and manage your account.

An account was already registered with this email. Please check your inbox for an authentication link.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. If you value our coverage and want to support more of it, please join us as a member.

‣ Robert Colquhoun and Bobby MacBryde were once household names in the London art world, until they weren’t. Author Damian Barr writes in the Guardian about the now-obscure artists, whose lives he attempts to recreate in his new novel:

I stumbled across them as footnotes in the biographies of people who used to want to be them. Soho survivors claim Francis Bacon is supposed to have said “Everything I learned about drawing, I learned from Robert Colquhoun.” Endless enraging articles describe them as “friends” or “roommates”: polite closeting elisions, more final than any coffin. When Bobby was 27 he wrote to Robert: “We must be certain to create our legends before we die.” By the time I discovered them they were almost forgotten. Could fictionalising them bring them back?

Obsessing, I found them in an issue of the Picture Post from 1949 with Prunella Clough, Keith Vaughan, Patrick Heron and John Minton (Minty). Rich Minty was in love with Robert and would eventually move into their studio, making a couple a throuple – that’s a fun chapter. The Roberts’ interview is titled The Artists Who Live, Travel, Work and Exhibit Together. The photo, by Felix Man, shows them at their easels in matching shirts and ties. Robert is in a fisherman’s jumper probably knitted by Bobby who made most of their clothes, ironing Robert’s shirts with a spoon heated on their single gas ring. On the easels are Bobby’s Woman in a Red Hat and Robert’s Two Scotswomen – both bought by Alfred Barr, the first director of the Museum of Metropolitan Art and sadly no relation. On a mission to acquire the best young British artists, Barr’s other purchases were Bacon, Edward Burra and Lucian Freud.

‣ After a protest, what happens to the visual language of its art and signage? Aaron Boehmer explores the rich lineage of typography used in social movements for Carla:

Get the latest art news, reviews and opinions from Hyperallergic.

Through their publishing platform GenderFail, the artist Be Oakley coalesced these individual moments, both from the Gay Liberation Movement, to create a single, downloadable typeface called “I am your worst fear; I am your best fantasy / FIRST GAY AMERICANS.” This typeface and nine others produced since 2018 were the subject of Oakley’s 2024–25 exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Each of Oakley’s fonts are derived from distinct but intrinsically interconnected socio-political movements—from the Stonewall Riots in 1969 and ACT UP in the 1980s and ’90s, to the resurgent calls for Black liberation in 2020, and the student uprisings for Palestine in 2023–25. The fonts are symbolically meaningful, wherein the “uppercase letters [do not have] any hierarchical importance over lowercase letters.” But they are also meant primarily to be useful, readily downloadable for queer, trans and non-binary folks, and queer people of color to use for protest signs, fundraising and mutual aid purposes, personal projects, and more.

In this way, an archive of past protest typography is transformed into a tool for the present and future. Oakley engages with the archive of protest not as a fixed or nostalgic look at the past, but as a dynamic and living resource—a place from which a movement can be both catalogued and continually reimagined. The “I am your worst fear” typeface is not merely a symbol of queer history, but an instrument for queer futurity, allowing generational knowledge from a movement that has been decades in the making to be passed down, active and defiant.

‣ Five Palestinian women reflected on cherished objects from Gaza, as told to the Cut‘s Danya Issawi. Artist Rama Duwaji, Zohran Mamdani’s partner, crafted quietly moving illustrations of the items they shared, from a portrait of two nieces to a handmade blanket:

When I left, about a week before the Rafah invasion, I could pack only a single suitcase. My home had already been destroyed by bombs, and I pulled some of my belongings from the wreckage. The blanket reminds me of my mom — she made it herself. I used to join her in the living room when I got home from work; we would watch YouTube as she crocheted. She tried to teach me the stitches a few times, but I just didn’t have it in me. She is still alive, thank God, though she is still in Gaza. Our names were on a wait list for evacuation, and mine was called before hers. Now she is trapped. No one has been allowed to leave. My mother keeps reassuring me and my sisters that better days are coming. I think she is also trying to reassure herself.

‣ Two decades after Hurricane Katrina, artist Kristina Kay Robinson reflects on the soul of New Orleans and the ways the city has failed its Black communities in Harper’s Bazaar:

This anniversary month, to cope with my post-traumatic stress, I’m reading Muhammad Khudayyir’s 2007 novel, Basrayatha. In it, the author presents both the historical and contemporary city of Basra, Iraq, alongside the mythical “Basrayatha,” which is a reconstruction of the city through memory and storytelling. In the section titled “Abu al-Khasib: Story Road,” Khudayyir writes, “Imagine with me a man whose job is collecting stories. What road would he take? What would he ride? Who would he be?”

“It’s important not to cede the story at the crossroads,” I wrote a decade ago. Even in 2015, we had already become a smaller, whiter city. Every public-school teacher in Orleans Parish (including my mother) was fired just months after Katrina’s landfall, making New Orleans the first all-charter-school system in the country. Twenty years later, the ramifications rear their heads. A major pathway to Black homeownership and wealth—stable, union-protected employment in the public-school system—was blocked off by those in power in New Orleans, with those who would teach our children their history stymied by charter-school politics. Public schools were also a major artistic incubator. Many of our teachers were artists, musicians, and thinkers in their own right, and they fostered an environment that held our culture together, a part of the lineage of artists that included my great-aunt, Gloria Ann Dupre, and those who came before her.

‣ For Wired, Taylor Lorenz reports on a shady initiative that allegedly paid influencers to boost Democrats online, as long as they adhered to content restrictions and did not disclose their funding — raising questions about media literacy and dark money in both parties:

For years, Democrats have struggled to work with influencers. In 2024, President Joe Biden’s White House snubbed several prominent content creators after they lightly criticized the administration over its policies on climate change, Covid, Gaza, and the TikTok ban. Content creators who challenged Kamala Harris—including Hasan Piker, a well-known influencer on the left—were similarly unwelcome at campaign events.

After the Democrats lost in November, they faced a reckoning. It was clear that the party had failed to successfully navigate the new media landscape. While Republicans spent decades building a powerful and robust independent media infrastructure, maximizing controversy to drive attention and maintaining tight relationships with creators despite their small disagreements with Trump, the Democrats have largely relied on outdated strategies and traditional media to get their message out.

Now, Democrats hope that the secretive Chorus Creator Incubator Program, funded by a powerful liberal dark money group called The Sixteen Thirty Fund, might tip the scales. The program kicked off last month, and creators involved were told by Chorus that over 90 influencers were set to take part. Creators told WIRED that the contract stipulated they’d be kicked out and essentially cut off financially if they even so much as acknowledged that they were part of the program. Some creators also raised concerns about a slew of restrictive clauses in the contract.

‣ Robin D. G. Kelley, who has written extensively about Black culture and subverting institutional power structures, considers the newly urgent responsibility of academics during an age of fascism and genocide. He explains for the Boston Review:

Moving beyond the ivory tower does not mean abandoning the university. The university is still contested terrain, and groups such as Scholars for Social Justice, the African American Policy Forum, and the Smart Cities Lab have managed to carve out spaces for resistance and visionary planning from within. UCLA’s Institute on Inequality and Democracy, founded by Ananya Roy, is an exemplary model of what insurgent intellectual work can look like. For the last ten years, the Institute has not only effectively fought for affordable housing and against racial banishment but developed a dynamic activist-in-residence program to provide space for movement intellectuals—from South Africa to Chicago to here in Los Angeles—to think with scholars in order to better understand the forces pushing people into greater precarity and find ways to fight back.

In order to sustain this work, we need to create a new university. And we will never change anything unless we are organized. Unionizing all faculty and teaching staff is not just about salaries and teaching loads, but about academic freedom, free speech, and the right to protest. Our efforts to build solidarity on campuses have tended to be around something bigger, about values and intervening in the world. Yes, we do this in our classrooms all the time, which is why the state and our university admins try to monitor everything we do. But it’s when we seek to build power, expand governance, take the offensive, and recognize our responsibility to transform this world, that the hammer falls. And the myth of the liberal university, of the transcendent intellectual, of the power of reason shatters at once. The lesson is that defeating the fascism we face now requires much more than defeating the current administration or winning elections. It requires a deeper shift: the recognition that we need to always stand in solidarity and fight for others as if our lives depended on it.

‣ Earlier this week, a devastating earthquake in eastern Afghanistan killed over 2,000 people, with the death toll rising by the hour. Chad de Guzman has a round-up of organizations accepting donations for disaster aid in Time:

Health-focused relief and development organization Americares has responded to previous quakes in Afghanistan and other quakes around the world. It said in a press releasethat it is ready to give emergency funding to its regional partner organizations to help restore health services in the most affected areas.

“Afghanistan has suffered multiple natural disasters in recent years compounded by years of conflict and crises that have affected over 23 million people,” said the organization’s deputy senior vice president of emergency programs Provash Budden. “Right now, we’re focused on meeting the most urgent health needs of earthquake survivors to help them recover during this incredibly difficult time.”

‣ Oksana Mironova contextualizes the resurgence of boxing, especially among women in places like New York City, in the history of anti-racism and feminism in the sport for Lux Magazine:

I am not alone in mining boxing for potent symbolism. Authoritarians of all stripes — who excel at weaponizing working-class culture to gain and hold power — have long recognized boxing’s potency. On the international scale, President Vladimir Putin’s regime in Russia has tried to rebuild the (brutal) Soviet amateur boxing training system that feeds into the Olympics while taking over the International Boxing Association (IBA) to “uphold Russian soft power.” More recently, Saudi Arabia has sought control over the professional side of the sport in a multi-billion dollar sportswashing exercise. Closer to home, police departments across the United States use the Police Athletic League’s boxing classes and mentorship programs to exercise soft power over the communities they police.

Central to boxing’s potential for fascist co-optation is what sociologist Kath Woodward calls the “heroic narrative” of the absolute triumph of a singular, cis, non-disabled male body. In American boxing this narrative is deeply racialized, epitomized by the 1910 white pogroms that followed Black heavyweight champion Jack Johnson’s defeat of James “The Great White Hope” Jeffries. A half-century later, Muhammed Ali would subvert this white nationalism by making a stand against the Vietnam War part of his own heroic narrative.

‣ Jaws turns 50 this year, and scientists are jumping on the opportunity to give sharks a “PR makeover” and channel some of the attention around the film’s anniversary into environmental awareness. Rosanna Xia writes for the Los Angeles Times:

“The shark in an updated ‘Jaws’ could not be the villain; it would have to be written as the victim, for, worldwide, sharks are much more the oppressed than the oppressors,” Benchley wrote in an essay in 1995. “It has been estimated that for every human life taken by a shark, 4.5 million sharks are killed by humans.”

But seeing all the renewed excitement for “Jaws” this year made me appreciate the feelings of commonality (and dare I say, hope?) that this cultural phenomenon has brought about. In a year where our politics have become more polarized than ever, this shared fascination with sharks has been a refreshing, less-controversial way to care about the ocean.

“I’ve been somehow made aware of ‘Jaws’ every single day this year — and not in a negative way. It’s very uniting,” said Jaida Elcock, a shark biologist with WHOI’s Marine Predators Group who runs @soFISHtication_, a popular animal-facts page on Instagram and TikTok. “Everyone knows this movie, and even if there’s sometimes differing opinions, you can strike up a conversation with a stranger just because it’s the 50th anniversary of ‘Jaws.’”

‣ My girl Nonprofit Boss is back:

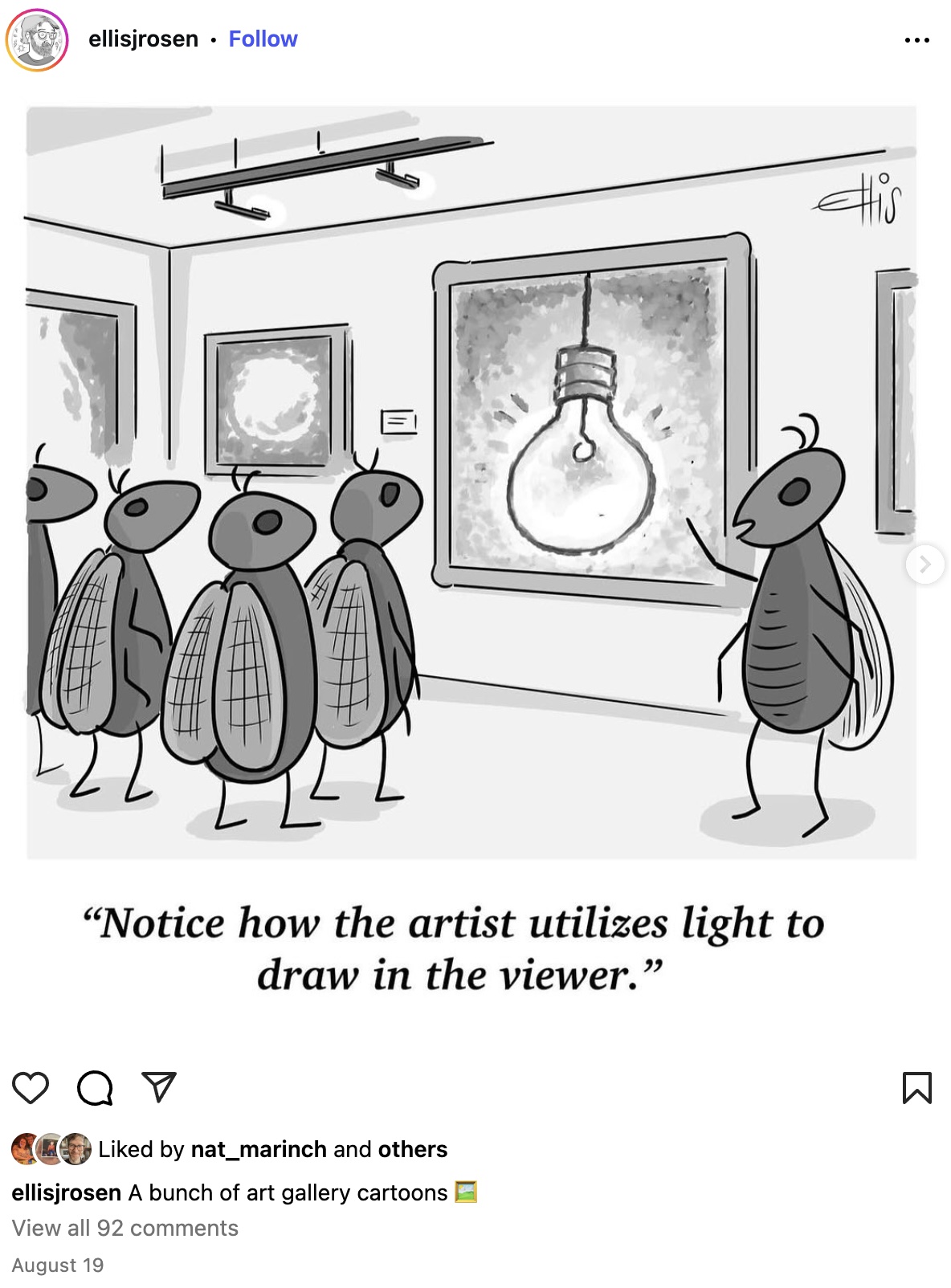

‣ Moths to a flame were the original chiaroscuro:

(screenshot via @ellisjrosen on Instagram)

(screenshot via @ellisjrosen on Instagram)

‣ Don’t go giving them ideas!

Required Reading is published every Thursday afternoon and comprises a short list of art-related links to long-form articles, videos, blog posts, or photo essays worth a second look.

Please consider supporting Hyperallergic’s journalism during a time when independent, critical reporting is increasingly scarce.

We are not beholden to large corporations or billionaires. Our journalism is funded by readers like you, ensuring integrity and independence in our coverage. We strive to offer trustworthy perspectives on everything from art history to contemporary art. We spotlight artist-led social movements, uncover overlooked stories, and challenge established norms to make art more inclusive and accessible. With your support, we can continue to provide global coverage without the elitism often found in art journalism.

If you can, please join us as a member today. Millions rely on Hyperallergic for free, reliable information. By becoming a member, you help keep our journalism independent and accessible to all. Thank you for reading.