Sarah McEachern traces the merging images of Annie Ernaux’s “The Other Girl,” newly translated by Alison L. Strayer.

The Other Girl by Annie Ernaux. Translated by Alison L. Strayer. Seven Stories Press, 2025. 96 pages.

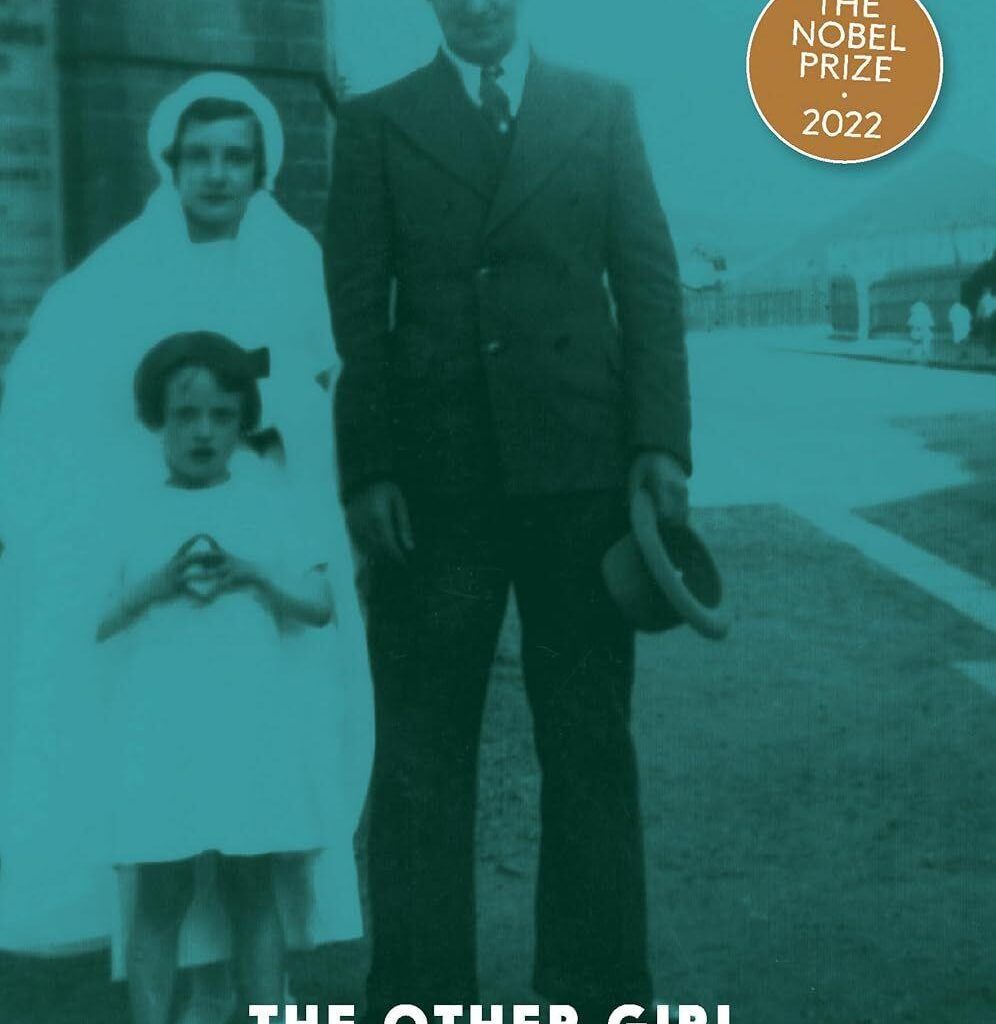

PERHAPS WE’RE BY NOW mature enough to admit that we do judge books by their covers all the time. The cover of the Seven Stories Press edition of Annie Ernaux’s The Other Girl, newly translated by Alison L. Strayer, offers itself to the reader as a key to unlock and understand the text, in addition to Ernaux’s project of life writing. Although I’ve admittedly picked up copies of Fitzcarraldo’s blank white editions of her English translations, there is a singular merit to the Seven Stories covers, which incorporate photos of Ernaux herself. On the cover of The Other Girl, however, there is no Ernaux but rather the title character—Ernaux’s older sister Ginette, who died nearly two years before Ernaux was born. In the slim edition, this same image is the penultimate photo presented in the text among five other photos, some including Ginette, and some of which depict Ernaux as a child. These photos provide the text’s main touchpoints, with Ernaux’s writing focused on observing and closely analyzing this visual evidence of the sister she never met.

The photo on the cover is from 1937, a decade that Ernaux never existed in, having been born in 1940. Regardless, she has a survivor’s knowledge of key facts, such as the camera the photo was taken on having been “won at a fair before the war, and which [her parents] kept until the end of the fifties.” Ernaux’s father, hat in hand, dominates the frame and towers over a cousin in her first communion dress. Ginette stands in the foreground of the mise-en-scène, her hands pensively held in front of her. From the cover, we’re introduced to the subject of The Other Girl—the mysterious sister Ernaux never met, whose short life of six years nonetheless directly impacted and shaped Ernaux’s understanding of herself. Ernaux addresses Ginette: “Because of the white-against-white of the two dresses you seem to merge into the other girl, the communicant whose veil covers your upper arms.” This is the second occurrence of this theme that runs throughout the narrative—the experience of merging. It appears immediately on the first page, when Ernaux describes a baby photo of Ginette, writing: “When I was little, I believed—I must have been told—that the baby was me. It isn’t me, it’s you.” As she does on the cover, Ginette remains elusive, merging with others.

The Other Girl isn’t long—only 96 pages—and Ernaux writes it as a meandering letter, addressed in the second person to Ginette. She wonders frequently about how Ginette’s death was the inspiration for her own conception and resulting propulsion into the world. She says, “So you had to die at six for me to come into the world and be saved.” Because her parents never speak of Ginette, Ernaux spends years of her childhood in ignorance of the sister that came before her, thinking herself a spoiled only child. Her later understanding of this other girl is one of the remarkable events of Ernaux’s life, making it eligible to become an installment in the large-scale project of Ernaux’s life writing, the undertaking that ultimately won her the Nobel Prize in 2022.

With nearly 50 published works in French, Ernaux has been steadily coming into English translation since 1990. The Other Girl, which was originally published in 2011, fits keenly in Ernaux’s project, with its now familiar themes and interests, but it has taken almost 15 years for it to emerge in English. Other books appeared much sooner in English, such as A Girl’s Story, originally published in French in 2016 and then translated in 2020. Ernaux’s Nobel has hastened some of her small and often overlooked works, like The Use of Photography (2005), which went almost two decades before entering the English market. Likewise, The Other Girl is a clear extension of her scrutiny of image-making. Here, two concepts of the image (memorial and photographic) form the other sisters of the text—who, like the Ernaux sisters, merge and compete for the best medium to understand and access the past.

The Other Girl is an examination of an event that shaped one Ernaux’s life trajectory. Although unwitnessed and unknown to her, Ginette makes Ernaux who she is, makes her accomplishments possible, and creates the definitions of her early childhood. She goes so far as to assert that “I do not write because you died. You died so I would write; that makes a big difference.” But Ernaux is working from a void—and, for years, even from an ignorance of this void. “I feel I have no language for you,” she admits, “as if I cannot talk about you except through the mode of negation, of continuous nonbeing. You are outside the language of feelings and emotions. You are the anti-language.” Impenetrable by shared experience and untouched by Ernaux’s usual “sharp as a knife” writing, this mysterious other girl is “an empty form, impossible to fill with writing.” So Ernaux turns toward other touchpoints: the six photographs, objects shared between the two girls’ childhoods, and her mother’s reference to her sister in a conversation that Ernaux overhears.

Ernaux extensively details the childhood bed that both girls slept in, where it was stored for most of her life, and how it was eventually lost. She remarks on how strange it is that this bed is a hand-me-down, shared between both girls, and outlines the ways they’ve shared other childhood artifacts, including their childhood home. As Ernaux writes, “I put these images in my books. So strange to think that they were images from your life too.” But it’s the sharing of parents that remains tricky, and Ernaux can’t help but feel territorial. “I’ve been unable from the start to write our mother, or our parents—to add you to the trio of my childhood,” she admits. Keenly and quickly, Ernaux notes that the two daughters received distinctly different versions of the same set of parents. Born to a working-class couple in Normandy who ran a grocery store and café out of their home, Ernaux had an experience of childhood in occupied France that was quite different from Ginette’s in the 1930s.

Ernaux has written about her father and mother in other books—respectively, A Man’s Place (1983) and A Woman’s Story (1988). She greedily admits that writing to Ginette is one way to be closer to their mother since it means “talking nonstop about her, the keeper of the story, the voice of judgment, with whom the fighting never ceased, except at the end, when she was in such misery, so lost in her madness, and I didn’t want her to die. Between her and me it’s a question of words.” Ernaux feels a strange sibling rivalry when it comes to her mother, grimacing at the idea of Ginette being born from the same body.

In her old age, Ernaux’s mother, lost to Alzheimer’s, is unable to remember most of the parameters of her life, but she tells a doctor that she has “two daughters.” This is one of only two times their mother speaks about Ginette in Ernaux’s presence. The other time forms one of the main events of the text: Ernaux overhears her mother discussing her sister with a customer in their store. “In the end, she says of you, she was nicer than the other one,” Ernaux recollects. “The other one is me.” The text moves, and the other girl of the title becomes Ernaux. The text plays into this idea of duality: the good one and the bad one. Most importantly, though, the two girls merge with each other and then separate into different places from where they started. What’s left is the chilling experience of childhood destabilization.

Like the two girls merging in the white of their dresses in a photo from the 1930s, like the two sisters mirroring each other in the memories of an aging parent, like the baby photo that feels like a hologram on the first page, Ernaux is interested in the merging and doubling of images. There is the image of memory, which proves piercing yet also corrupted by time and ego, and the images of photography and film, which don’t always match memory but nonetheless remain fixed. The author has touched on similar ideas before, in The Use of Photography, which deploys a familiar trope of Ernaux’s work—a love affair—to examine her changing understanding of self-image during her treatment for cancer.

Ernaux’s 2022 documentary film The Super 8 Years, made with her son David, is an important facet of her project of life writing, although it’s often left out of her oeuvre. Constructed of family videos from 1972 to 1981, with Ernaux’s narration overlaid upon the moving images, this visual essay is arguably the author’s most experimental text. Ernaux didn’t keep a journal during the years of her marriage, which, coincidently, the Super 8 footage effectively covers. The film plays with the elusiveness of memory, pondering whether events are fixed in the mind by the bias of photographic images. In the world of smartphones and image-driven social media, it’s a fascinating question that Ernaux tries to tackle head-on. In The Other Girl, written a decade before her foray into film, the initial threads of the concept are noticeable. Ernaux reckons with how photographic images complicate her memory of a void, creating evidence of a lived experience she was not present for but nonetheless somehow experienced. Even photographic images, it seems, are as fickle and difficult to consult as the images held by memory alone.

Many consider Ernaux’s The Years (2008) to be her magnum opus, but for me, Happening (2000) is her strongest, most concise work. I saw Audrey Diwan’s 2021 film adaption first, however, and ventured to the Strand bookstore the same week to find my own copies of Ernaux’s writing. They only had A Girl’s Story, which I consumed and became obsessed with. Ernaux is tied to the visual for me, because my initial entry into her project was through a film, an adaptation of her account of procuring an illegal abortion. Difficult and dangerous in a France 12 years out from the Veil Act, the abortion nearly kills Ernaux. It’s one of the most traumatic events of her life.

What Ernaux is often writing about in her books is what Virginia Woolf describes as “moments of being,” rare instances in one’s life when one is fully alive, a stark clarity opposed to the mundane and monotonous. The event recounted in Happening is one of these moments, as is the overhead conversation in The Other Girl. Reflecting on what she’s heard, Ernaux thinks, “On that summer Sunday, I do not only discover my darkness, I become it with my whole being.” Ernaux takes Woolf’s concept one step further; the moment affixes itself to her, changing her being.

Ernaux’s project is interested in the strange and impossible nature of memory as much as it is in the specific events that shaped the author. While the memory of her mother describing the other girl as nicer than Ernaux herself seems to fit perfectly into the narrative of discovering her sister’s existence, Ernaux admits that it’s her cousin who first told her about her sister: “According to my cousin G., it was C., another cousin, who one or two years earlier had revealed your existence and your death to me.” But only one of these is “the day of judgment,” as she calls it, so in her memory, one experience emerges as paramount over the other, making them feel as if they occurred out of chronological order. Memory can twist and move. While Ernaux admits that she wants at times to pretend that her parents yearned for her good, dead sister, she admits that “the facts belie the myth,” and she was well cared for and loved through all of her childhood illnesses.

Images in memory present a special sort of fickleness and strangeness. When Ernaux recounts the story of overhearing her mother speak about her sister, she writes, “The scene of the story hasn’t budged, no more than a photo would.” Read swiftly, it would seem she is suggesting that her memory resists corruption, but read more closely, she clearly means the opposite. The text opens with the image of the infant, which blurs and merges its subject, making obvious that the photographic image is not to be viewed without skepticism. She remembers her mother and the words she said perfectly, but the out-of-focus woman merges with another character (“I now confuse her with the director of a summer camp where I worked as a monitor in Ymare, near Rouen, in 1959”). The holographic effect of images appears again, but this time via the images of memory instead of photographs.

Ernaux writes that the stories about the war from her infancy, when recounted by her parents, remained “devoid of images and words,” and that they “left no trace in [her] consciousness.” But even when images and words cause an impression, they are still subject to change in eerie ways, especially those early in life. “Nothing that happens in childhood has a name,” she asserts. There is no language to grasp at for support. But, of course, more than almost anything else, childhood determines who we become. Ernaux’s project of life writing, as straightforward as its goals may seem, becomes very complicated when she starts to try to pin down crucial events, only to find that memory, language, and image all have their faults.

Ernaux expresses her own doubts about The Other Girl as an installment in her project, admitting by the end of the book that her reason for “start[ing] it in the first place remains a mystery.” The text won’t reach her sister or her parents. She is writing about a stranger in her own family. Ernaux’s project traces out a mosaic of moments and events that shape not just her life but also her very being. In one of the most striking passages, she writes, “I am overwhelmed by the expanse of my life, infinitely larger than yours. The things that are behind me are innumerable, things seen and heard, learned and forgotten—women and men I’ve met, streets, mornings and evenings. I feel overwhelmed by the profusion of images.” Ernaux’s striving to collect her memories is an undertaking to understand herself as much as it is a testing of the boundaries of language and image.

LARB Contributor

Sarah McEachern is a reader and writer in Brooklyn, New York. Some of her recent writing has been published by the Ploughshares Blog, BOMB, The Believer, The Rumpus, Split Lip Mag, and Full Stop.

Share

Copy link to articleLARB Staff Recommendations

Alina Stefanescu reviews “The Use of Photography” by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, newly translated into English by Alison L. Strayer.

Apoorva Tadepalli reviews Annie Ernaux’s “Look at the Lights, My Love.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!