When most people think of dreaded diseases or conditions, cancer, heart disease or dementia usually top the list. But far fewer realize there’s a silent killer claiming hundreds of thousands of lives each year: sepsis. Making matters worse, this life-threatening condition can begin from something as seemingly harmless as pneumonia, a urinary tract infection or even a deep cut.

In the U.S. alone, sepsis strikes at least 1.7 million adults annually and contributes to some 350,000 deaths, per the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “And it is a leading cause of in-hospital death,” says Dr. James Morrison, a critical care and emergency medicine physician and chair of Cleveland Clinic’s enterprise sepsis steering committee.

Here’s what sepsis is, what causes it and how it’s treated if it affects you or someone you love.

What is sepsis?

Sepsis is a life-threatening medical emergency “that occurs when your body’s immune system has an overwhelming and dangerous reaction to an infection,” says Morrison. He explains that normally, the immune system identifies and controls invading pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, fungi or parasites. But when sepsis develops, the body’s defensive measures spiral out of control, triggering widespread inflammation, abnormal blood clotting and leaky blood vessels.

These changes can disrupt blood flow and reduce the delivery of oxygen and nutrients around the body and to vital organs. Left untreated, sepsis can lead to organ failure, tissue damage requiring amputation, septic shock and death.

Despite being so harmful, “sepsis can be challenging to identify because its symptoms can vary and mimic other conditions,” Morrison notes. Still, there are hallmark patterns to look for. These symptoms “are collectively referred to as the acronym TIME,” explains Purvesh Khatri, a professor of medicine at Stanford University:

Temperature changes: fever or signs of hypothermiaInfection: evidence of infection anywhere in the bodyMental decline: confusion, disorientation or drowsinessExtremely ill feeling: severe pain or discomfort

Other warning signs that Morrison highlights include a rapid heart rate, low blood pressure, difficulty urinating, clammy or discolored skin and respiratory issues such as rapid, shallow or labored breaths.

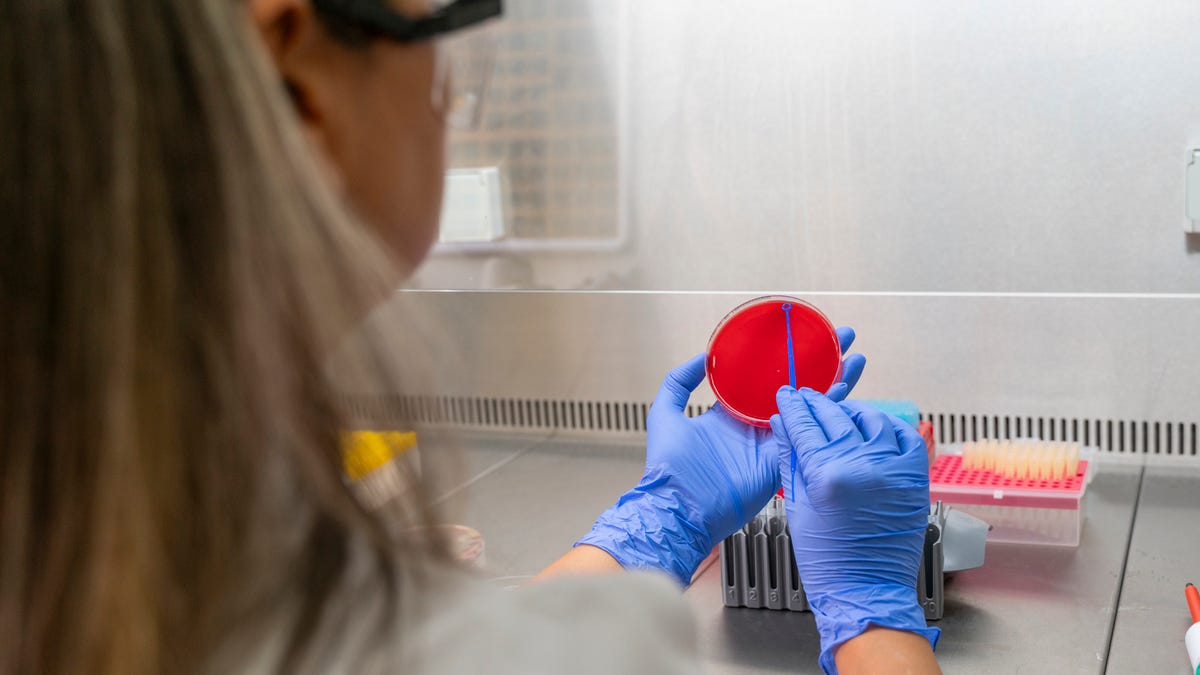

Diagnosing sepsis involves a combination of approaches such as checking vital signs (temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, breathing rate), lab testing (blood cultures, metabolic panels, lactate levels) and sometimes imaging studies like X-rays, CT scans or ultrasounds to help identify the source of infection.

What causes sepsis?

Sepsis develops when an infection triggers a harmful immune response. “Bacterial infections are one of the most common root causes,” says Morrison, “but fungal, viral or parasitic infections can also lead to sepsis.”

These infections can originate anywhere in the body, he adds, but most often start in the lungs, urinary tract, skin or gastrointestinal system.

And while anyone with an infection is at risk, certain groups are especially vulnerable. Adults over 65 and infants or very young children, for instance, face higher risk because of weaker or still-developing immune systems. Pregnancy also brings increased susceptibility. People with compromised immune systems, such as those undergoing chemotherapy, living with HIV or taking immunosuppressive drugs, are amore vulnerable as well. The same goes for anyone with chronic illnesses like diabetes or kidney disease.

Hospitalized patients face elevated risk, Morrison adds, particularly those in intensive care units where invasive devices such as catheters or ventilators are commonly used and can increase exposure to infection.

How is sepsis treated?

Because of its severity, “sepsis requires treatment initiation as quickly as possible,” says Khatri. The goals of treatment are to control the infection, stabilize the patient and support any organs that are affected or failing.

To accomplish this, “treatment typically includes supportive care to manage symptoms, antibiotics to fight the underlying infection and IV fluids and medications such as vasopressors to restore blood pressure,” Morrison explains. “In some cases, surgery may also be necessary to remove the source of infection.”

Once a patient is stabilized and discharged, recovery often continues at home or during rehabilitation. Patients often need time to rebuild strength, regain organ function and recover from complications such as muscle weakness or cognitive difficulties. Rest, hydration, proper nutrition and careful follow-up care that includes completing prescribed antibiotics and monitoring for relapse are also essential.

Early evaluation and treatment are critical because sepsis progresses rapidly, and prompt recognition and interventions can mean the difference between life and death. “Each hour of delay in treatment,” cautions Khatri, “brings with it an increased mortality risk.”