“The world is talking about Argentina’s economic miracle!” Javier Milei exclaimed in August of last year before a hundred businesspeople gathered at the Council of the Americas conference in Buenos Aires. “Everyone sees it, except the Argentines,” he immediately lamented, aware of his audience’s skepticism, since they were cautious about committing their investments. The far-right leader had been president of Argentina for eight months and boasted of having launched “the largest fiscal adjustment in the history of humanity.”

Those were times of euphoria and hyperbolic statements: at that point, the country had achieved a fiscal surplus, inflation had fallen from 20% monthly in January to under 5% in June, the economy was projected to grow nearly 4% in the third quarter — after a 1.8% decline in the first — and household consumption was soaring, supported by the return of credit and a cheap dollar. Economy Minister Luis Caputo was “a colossus,” and his critics were “charlatan economists” and “sodomized mandrills.”

Times have changed very quickly. A year after that festive event, Milei’s so-called miracle is faltering. But help could be on the way: following Milei’s trip to New York for the United Nations General Assembly, U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent announced on Wednesday that the White House was negotiating a $20 billion currency swap to strengthen the Central Bank’s reserves, the purchase of Argentine debt bonds, and a “significant stand-by credit via the Exchange Stabilization Fund,” the amount of which was not specified. Argentina’s country risk fell from just over 1,000 points at Tuesday’s close to 839 points at the opening, a drop of almost 18%. It’s still far from the 500 points of a year ago, but it represents a notable improvement over the 1,500 points it reached the previous week.

In December 2023, Milei’s far-right government inherited a country with a broken currency, skyrocketing inflation, and a bankrupt Central Bank. Milei then implemented a shock therapy: he floated the exchange rate and countered the resulting inflation spike with fiscal adjustment, zero money issuance, and the termination of government financing through the Treasury. All of this was seasoned with a “cultural war” against “the caste”: any criticism was met bluntly with all kinds of insults, his spokespeople celebrated the firing of 50,000 public employees, and publicly questioned why a doctor should earn a good salary if, after all, “they are fulfilling their dream.”

The markets, focused on the numbers, overlooked the uncomfortable details and embraced Milei. Finally, one of their own was easing financial restrictions, cutting taxes, and calling tax evaders “heroes.” Argentina’s country risk — the premium it pays on its debt relative to U.S. bonds — fell from 2,500 points in 2023 to around 500 points in January 2025. In other words, Argentina could borrow at much lower rates.

The model, however, had a problem. The monetary anchor that Milei used to control inflation resulted in an overvalued peso and the need for dollars to flow into the system to sustain the exchange rate. “At the start, he secured $22 billion from a tax amnesty and then another $20 billion from the International Monetary Fund,” says Marina Dal Poggetto, director of the consulting firm EcoGo. “But the government never regained access to international credit and continued to pay its debt maturities.”

The turning point came in April of this year, when Milei, backed by the IMF bailout, lifted the cepo — the Argentines’ name for currency controls — and allowed the official dollar to float within bands. This move was reversed on Friday, banning individuals who buy dollars at the official rate from accessing financial exchange markets for 90 days. The goal is to stop a speculative maneuver known as rulo or puré, where investors profit by buying cheap official dollars and reselling them at higher financial market rates — draining Central Bank reserves.

“When he lifted the controls on individuals, Argentines bought $14.7 billion for savings. As long as exporters were supplying the market, things worked and the exchange rate stayed within the bands. But once the dollars stopped coming in and demand held steady, the government carried out an unprecedented monetary squeeze to ease the pressure,” says Dal Poggetto.

To reduce the amount of pesos in circulation, rein in the dollar, and keep inflation in check, the government raised bank reserve requirements (the deposits banks are required to hold and cannot lend) to 53% and paid interest on peso deposits of nearly 80%.

Stagnant activity

The consequence of those sky-high rates was a freeze in economic activity. The latest report from the Argentine Center for Political Economy (CEPA) notes that overdraft loans averaged a real rate of 49.8%, which meant an additional financing cost of about $100 million for businesses. “After the V-shaped rebound in economic activity in 2024, the first half of 2025 shows clear stagnation, and since February there’s been a downward trend that could turn into a recession in the second half. If this level holds until year-end, the economy would rebound 4% compared to 2024, a figure below the IMF’s 5.5% projection,” the consulting firm warns.

Data from INDEC, Argentina’s national statistics office, confirmed the decline in economic activity in its second-quarter 2025 report released on September 18. GDP grew 6% year-on-year but fell 0.1% compared with the first quarter. Consumption dropped 1.1% in the same period. Overnight, Milei suddenly became an economic heterodox.

Driven by the need to keep inflation in check ahead of the national legislative elections on October 26, Milei resorted to a patchwork policy that can hardly be sustained in the long run. The market, little by little, lost patience.

On September 18, the market made it clear. Country risk closed at 1,453 basis points, 16.6% higher than the day before and double the level in August. Argentine foreign-currency bonds plunged by as much as 14%, and the central bank was forced to sell $379 million from its reserves to contain the surge in the exchange rate, which for the second consecutive day had reached the upper band of 1,474 pesos set by the government. The next day brought no relief: it sold another $678 million in a week when country risk finally broke through 1,500 points.

“Sentiment had already been fraying since last July’s unwinding of the LEFIs [a Treasury bill operation that injected 10 trillion pesos into the money supply, putting pressure on the exchange rate and inflation]. And since then, they haven’t gotten a single move right,” says a trader at one of Argentina’s top investment firms, who asked not to be named. “There was no need to dismantle the LEFIs, and everything was done badly. Reserve requirements were raised multiple times, which hit banks hard because it shrinks their business. Every peso a bank has to hold in reserve is a peso it can’t use elsewhere. We saw absurd levels of interest rate volatility, which doesn’t help anyone either. All of this speaks to poor practice,” he complains.

The response of those with savings capacity was the same as always: buy dollars, with the central bank’s accounts in the red. In July alone, $5.43 billion shifted into private hands. Sociologist Ariel Wilkis, coauthor of the book The Dollar: History of an Argentine Currency, notes that Milei’s government was not spared from the usual “dollarization process that takes place in the months before elections.” “This process clashes with Milei’s narrative of citizen support for his policies,” he emphasizes.

For Wilkis, “Milei’s miracle was making an adjustment with popular support.” The far-right leader was the first and only candidate in Argentina’s history to come to power promising to slash public spending. Against many forecasts, he retained support close to 50% even after raising electricity, gas, and public transport prices; laying off public employees; and even cutting pensions, university budgets, and funding for national reference hospitals.

Milei boasted both domestically and abroad about citizen backing for his policies, but that image crumbled in the legislative elections in the province of Buenos Aires, where he finished nearly 14 points behind the Peronists.

View of the Padre Carlos Mujica neighborhood (known as Villa 31), in Buenos Aires.LUIS ROBAYO (AFP / GETTY IMAGES)

View of the Padre Carlos Mujica neighborhood (known as Villa 31), in Buenos Aires.LUIS ROBAYO (AFP / GETTY IMAGES)

The causes of the electoral defeat are multiple. In the past month, a senior official linked the president’s sister, Karina Milei, to a case of bribery involving the supply of medicines to people with disabilities. There were also political mistakes by an inexperienced government reluctant to accept help from its temporary allies. But without a doubt, the economic hardships explain most of the outcome.

Argentines are celebrating the drop in inflation, which had been devouring wages faster and faster, but they are frustrated at not making ends meet despite cutting expenses and working longer hours. Some have even resorted to loans they later could not repay: credit card delinquencies rose from 1.9% in June to 4.4% in July, and personal loan defaults climbed from 4.1% to 6.4% over the same period, according to the Central Bank. These are the highest levels since early 2024, when Milei’s 50% peso devaluation and the subsequent inflation spike upended all household budgets. “The paradox of the current context is price stability in tension with income scarcity,” says Wilkis.

The phenomenon Wilkis describes is not, however, new in Argentina. A similar situation occurred in the 1990s, when the peso’s convertibility with the dollar, implemented by the liberal Peronist Carlos Menem and his Economy Minister Domingo Cavallo, ended hyperinflation. The cost was an unprecedented productive paralysis, rising unemployment, and the closure of thousands of small businesses, especially in the provinces.

The system worked, as it does now, as long as the economy received dollars — then through the privatization of dozens of state-owned companies and borrowing. Once the flow ended, exchange rate pressure became unbearable, and everything came to a head in December 2001, with the corralito crisis — when Argentines were unable to freely withdraw money from banks — and the declaration of a massive default.

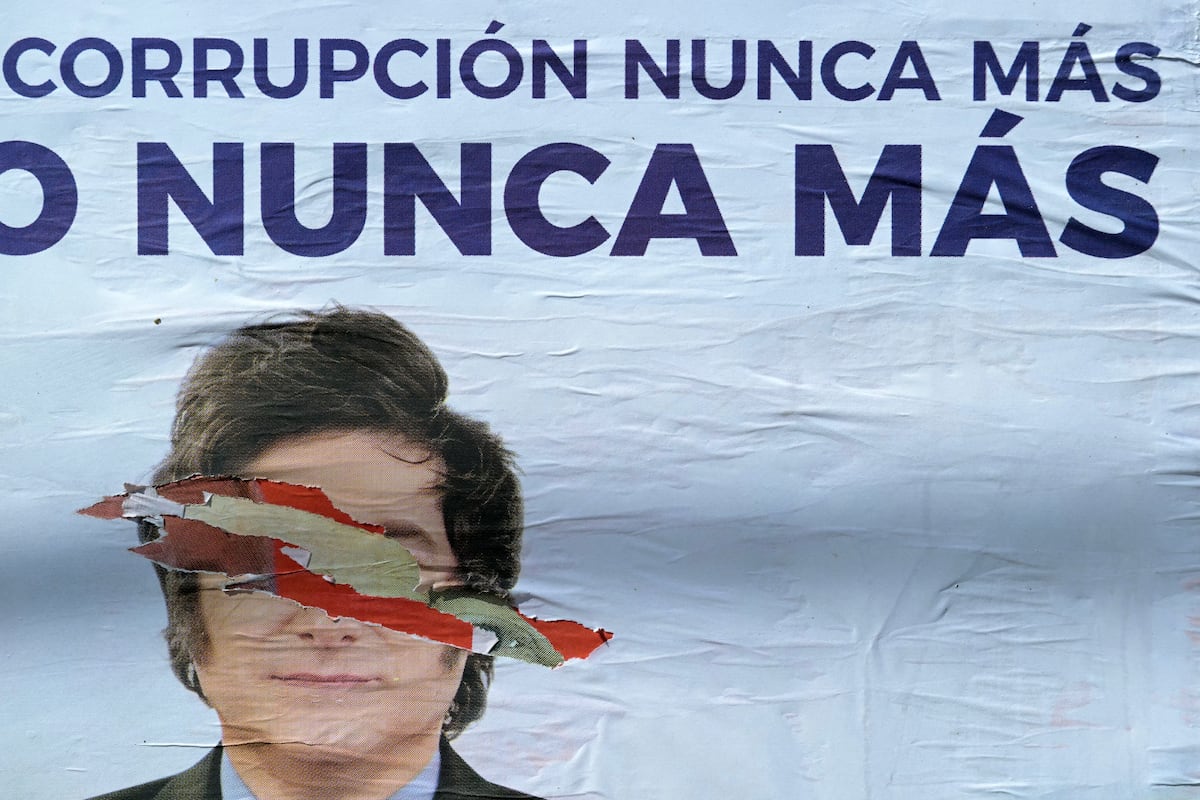

No one is thinking about those dark years, but they are warning Milei that things are not going as well as he likes to promote. The elections in Buenos Aires were an unexpected slap in the face for the government, a rude awakening for Milei, who appeals to “forces from heaven” to carry out what he considers a divine crusade against “socialism,” “the caste,” and “Kirchnerism,” which, in his view, are the source of all the world’s ills.

Protest against Milei in front of Congress on August 20.LUIS ROBAYO (AFP / GETTY IMAGES)

Protest against Milei in front of Congress on August 20.LUIS ROBAYO (AFP / GETTY IMAGES)

The polls reflected the crisis that followed the adjustment, especially in the province of Buenos Aires, home to 40% of the country’s population. Eduardo Donza, a researcher at the Social Debt Observatory of the UCA, states that the sacrifices demanded by Milei have fallen particularly on the middle class. Common expenses in this social stratum, such as private school tuition and health insurance plans — known in Argentina as prepagas — have risen far above the CPI, forcing families to tighten their belts or give up these private services. Families simply do not have enough money because incomes have not increased at the same pace to cover these costs and those resulting from the elimination of subsidies on electricity, gas, water, and transportation rates that were in place during the Kirchner administrations.

In some sectors, wages have kept pace with inflation; in others, they have fallen far behind, as is the case with public employees. Clothing and footwear factories, retail, and construction have lost jobs due to the consumption slowdown, import liberalization, growth of online commerce, and the total halt of public works. Construction has lost 73,415 jobs and industry 42,870 since Milei came to power, according to official data.

“Middle-class sectors, which could consume more, spend a large portion of their spending paying for services that have increased or on their children’s school fees, leaving them with less to spend than before. And this has a cost for employment, which is becoming increasingly precarious,” says Donza.

“Historically, the biggest problem in the Argentine labor market is precariousness, not unemployment, because those without formal employment have to find a way to find self-employment,” he continues. “We’re seeing precariousness and an increase in multiple jobs, among people who had good jobs but saw their incomes drop significantly, for example, public employees who are looking for other jobs, or retirees with fairly low incomes.”

The most vulnerable sectors were, in part, shielded from the adjustment thanks to the increase in state aid programs. Maintaining the social safety net and curbing inflation helped 1.5 million people rise out of poverty by the end of 2024 compared to the previous year. Yet the latest rate, 38.1%, still reflects Argentina’s socioeconomic deterioration after repeated economic crises.

“In Argentina, there is a high percentage of structural poverty that is very difficult to reduce. These are already the third generation, meaning people born into households where the parents were already poor, and they face very serious problems,” explains the researcher.

Elections

Milei’s focus is now on the midterm national legislative elections scheduled for October 26. His party, La Libertad Avanza (Freedom Advances), is in the minority in both chambers of Congress and needs to gain legislators to push forward the structural changes it proposes. Meanwhile, Milei is stirring fears of a return of Kirchnerism and the risk of all kinds of economic calamities to solicit votes. If the economy wavers, he claims, it is not because of mismanagement, but because investors fear the “Kuka risk,” a derogatory term for a potential electoral victory of Kirchnerism.

“The argument to support the model is that if populism doesn’t return, country risk will fall and credit will return. But Peronism won in the province of Buenos Aires, and the chances of it winning the national elections are high,” warns Dal Poggetto.

It remains to be seen whether another electoral defeat would fulfill Milei’s ominous predictions. Meanwhile, the government is attempting some political outreach to win over the allies it left behind.

“The ideas of freedom will sweep Buenos Aires,” Milei repeated during the last campaign — and he was wrong. Following his party’s defeat in Buenos Aires, the president announced the formation of a “political table” and a “federal dialogue” forum where he aims to bring together governors who, after initially supporting his administration, have now turned their backs on him.

The budget proposal he presented includes more funds for the provinces and slight increases in funding for public universities as well as health and education expenses. Milei appeared far more moderate: he refrained from insults and even avoided his usual rallying cry, “¡Viva la libertad, carajo!”, with which he typically closes his speeches.

Whether this shift toward moderation comes too late remains to be seen. Milei has not only lost the favor of the governors, but also of the moneyed elite. A disenchanted broker speaks of “fatigue” with Milei and his economic team. “They behave with absolute arrogance. We would like to see more professional management of politics and communications, because we are clearly not here to be arrogant. We’ll see if they have the capacity to react,” he says.

On the Monday following the Buenos Aires election, debt bonds collapsed, and Argentine company stocks fell up to 20% on Wall Street. For the first time, the exchange rate reached the top of its allowed range, 1,475 pesos, forcing the Central Bank to sell $54 million.

When profits fall, the manner in which things are done does matter.

Vaca Muerta facilities, an unconventional geological formation of gas and oil located in Argentine Patagonia.Matias Baglietto (NurPhoto / Getty Images)Foreign investment trickles in

Vaca Muerta facilities, an unconventional geological formation of gas and oil located in Argentine Patagonia.Matias Baglietto (NurPhoto / Getty Images)Foreign investment trickles in

The Argentina Oil & Gas fair, the country’s largest showcase for the energy sector, closed its annual edition after hosting over 400 companies and around 30,000 visitors — record numbers that highlight the sector’s appeal, especially its crown jewel, the vast unconventional hydrocarbon formation of Vaca Muerta in Argentine Patagonia.

Interest, however, is tempered by caution. Multinationals are wary of growing doubts about Javier Milei’s governance and Argentina’s persistent financing, infrastructure, and regulatory challenges. As a result, many are keeping their foot on the brake before committing hundreds of millions — or even billions — of dollars to medium- and long-term projects. Some have even opted to sell to the highest bidder and leave, such as the U.S. firm Exxon Mobil or the Spanish company Telefónica.

Since August 2024, Argentina has offered a generous 30-year fiscal, currency, customs, and legal incentive regime for companies presenting projects over $200 million (known as RIGI). Yet a year later, only seven projects have been approved, totaling $13 billion and estimated to generate about 1,000 direct jobs.

The largest initiative is a floating liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant off the coast of the Patagonian province of Río Negro. Approved investment so far is $6.878 billion for two vessels with a combined annual production capacity of six million tons of LNG, all intended for export, according to Southern Energy, the consortium of Argentine companies in charge.

Argentina opted for floating liquefaction after Malaysian firm Petronas withdrew from an ambitious onshore LNG project it had agreed to with state oil company YPF, estimated to be worth over $30 billion.

“We need the RIGI to protect these types of investments because otherwise they won’t be made. In other countries in the region, it’s not necessary,” said Ernesto López Anadón, director of the Argentine Institute of Oil and Gas, in a meeting with journalists. López Anadón also acknowledged that Argentina “needs to reform many things if it wants to be competitive” in international markets.

Pending reforms

Some long-demanded reforms — such as tax and labor law changes — cannot be implemented by presidential decree and require lengthy negotiations and consensus-building in Argentina’s fragmented Congress. Milei, who has shown little political skill over the past year and even burned bridges with some allies, has no way to advance these laws. His fortunes now seem tied to a strong showing in the legislative elections on October 26, when both chambers will renew a portion of their seats.

Politics is only one factor investors consider. At Argentina Oil & Gas, senior hydrocarbon executives stressed that the industry’s biggest bottleneck today is financing. High interest rates imposed by Milei have sharply restricted credit access, and external funds are also lacking. Argentine companies Tecpetrol and Pluspetrol indicated they will wait for macroeconomic conditions to stabilize before accelerating their planned investments.

The same uncertainty affects mining companies, one of the fastest-growing sectors in the coming years. British-Australian giant Rio Tinto has an approved $2.724 billion project in the northern province of Salta to produce up to 60,000 tons of lithium carbonate annually; Australian company Galan Lithium has another $217 million project to produce lithium chloride in the neighboring province of Catamarca.

One challenge is infrastructure for transporting raw materials from these extractive industries and the high cost of transport in a country spanning almost 2,735 miles (4,400 kilometers) north to south. Since taking office, Milei has halted public works, and roads nationwide are deteriorating. Trucks traveling on national highways connecting the north to Bolivia, Paraguay, and Brazil must navigate potholes caused by a lack of maintenance, and provincial authorities have warned of the growing risk of road accidents.

Of the 2,700 unfinished public works under the previous Alberto Fernández government, 54% saw no progress under the Milei administration. Sooner or later, the government will have to resume them, even if it adds pressure to the fragile fiscal balance.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition