This case highlights the rare occurrence of oculomotor nerve palsy in N. meningitidis meningitis. Cranial nerve involvement in bacterial meningitis is thought to occur through several mechanisms, including:

Direct bacterial invasion: Bacteria can directly invade the cranial nerves, causing inflammation and dysfunction.

Meningeal inflammation: Inflammation of the meninges surrounding the nerves can lead to compression and damage.

Vascular compromise: Inflammation can affect the blood supply to the nerves, resulting in ischemia and dysfunction.

In oculomotor nerve palsy, inflammation within the cavernous sinus or along the nerve’s intracranial course is likely implicated. The presence of mild diffuse cerebral edema and lacunar infarcts on CT brain suggests a potential role for vascular compromise in this patient’s presentation.

Cranial nerve palsies are reported rarely in bacterial meningitis cases. Among them, the sixth cranial nerve (abducens nerve) is the most commonly involved, with oculomotor nerve (CN III) involvement being the second most common.4 Notably, CN III is most commonly affected in tuberculous meningitis (TBM) (5,6,7). This predisposition of CN III in TBM, coupled with the patient’s origin from a TB-endemic region, significantly contributed to our decision to empirically initiate ATT. CN III palsy in N. meningitidis meningitis is often associated with other neurological complications, such as seizures, hydrocephalus, and cerebral edema. This case underscores the importance of considering these complications, even in the absence of other focal neurological signs.

Prognosis for recovery from cranial nerve palsies is generally favorable, though some patients may experience residual deficits [8]. Early diagnosis and treatment of the underlying meningitis are crucial for maximizing neurological recovery. The presence of cranial nerve palsy does not necessarily indicate a worse prognosis for the meningitis itself, but it highlights the potential for more severe neurological involvement.

This case also illustrates the diagnostic challenges posed by overlapping clinical presentations of bacterial and tuberculous meningitis, particularly in resource-limited settings. The patient’s origin from a TB-endemic region, coupled with the initial indeterminate QuantiFERON-TB Gold result, prompted consideration of TBM. The challenges in obtaining CSF, likely due to technical factors, further complicated the diagnostic process. Repeated fever spikes also raised concerns about the possibility of co-infection, drug resistance, or other complications.

The empirical use of ATT, while understandable in the context of diagnostic uncertainty, highlights the need for improved diagnostic tools and algorithms for differentiating between bacterial and tuberculous meningitis, especially in regions with high TB prevalence. Molecular diagnostic tests, such as PCR for M. tuberculosis in CSF, could potentially expedite diagnosis and guide appropriate therapy. TB PCR offers the advantage of rapid detection with higher specificity compared to conventional methods, enabling earlier differentiation between tuberculous and other forms of meningitis. This not only facilitates timely and targeted treatment but also helps reduce unnecessary exposure to prolonged ATT in patients without TB, ultimately improving patient outcomes and antimicrobial stewardship.

Oculomotor nerve (cranial nerve III) palsy is a rare but recognized neurological complication of bacterial meningitis, including infections caused by Neisseria meningitidis. While sixth cranial nerve involvement is more commonly associated with raised intracranial pressure (Sahin et al., 2020)[4,5,6,7,8,9], CN III palsy can also occur and may signal localized or severe meningeal inflammation, direct nerve involvement, or vascular compromise affecting the nerve’s course (Kami & Teixeira, 2023) [10].

Though less frequently reported than other cranial neuropathies, cases of CN III palsy in the context of meningococcal meningitis have been documented. Senda et al. (2019) described a case of bilateral oculomotor nerve palsy in an adult with N. meningitidis meningitis, highlighting that even in immunocompetent adults, such complications can arise [11]. The patient’s clinical presentation included ptosis and ophthalmoplegia, with neuroimaging revealing signs consistent with cranial nerve involvement. These findings emphasize the importance of considering focal neurological deficits in the early evaluation of suspected meningitis.

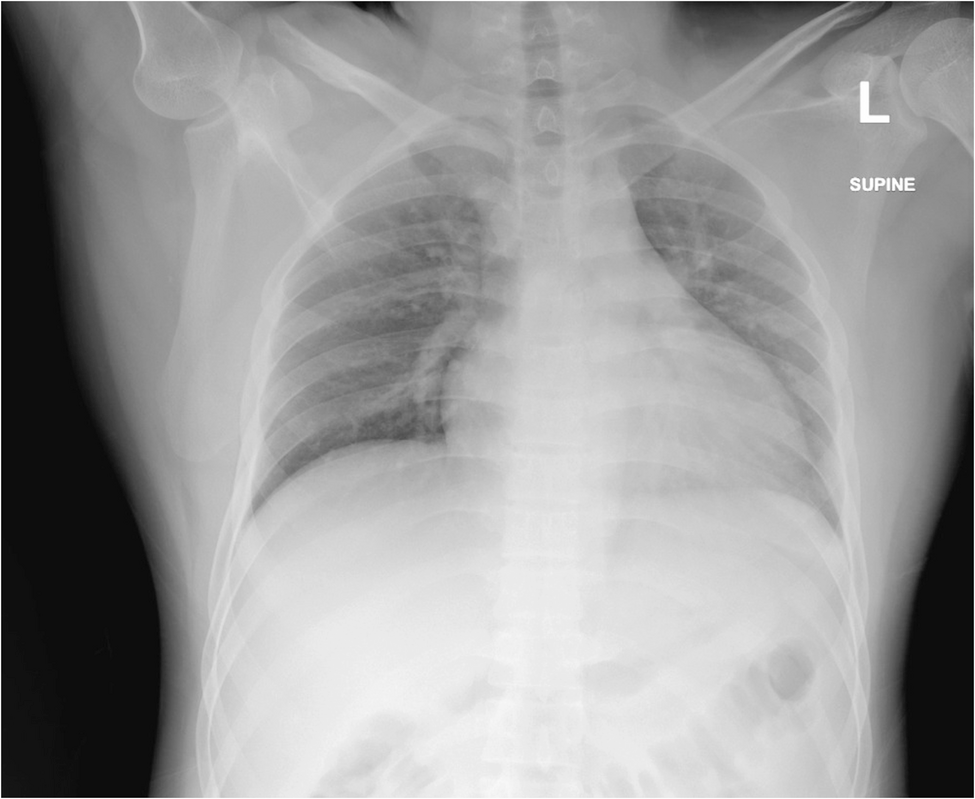

Neuroimaging plays a crucial role in detecting structural or inflammatory changes involving the cranial nerves, particularly when atypical neurological signs such as CN III palsy are present. MRI may demonstrate nerve thickening, enhancement, or adjacent meningeal inflammation, providing valuable diagnostic clues.

While uncommon, oculomotor nerve palsy in N. meningitidis meningitis serves as a reminder of the diverse neurological manifestations of this infection. Its presence should prompt urgent imaging and CSF analysis to guide appropriate diagnosis and management, especially given the potential for rapid progression and severe outcomes if left unrecognized.

Non-infectious causes of oculomotor nerve palsy should also be considered. Sahin et al. (2020) describe a case of episodic oculomotor nerve palsy associated with carcinomatous meningitis, emphasizing the importance of considering leptomeningeal metastasis in patients with cancer presenting with cranial nerve palsies. Velez Oquendo et al. (2024) also report a case of CN III palsy as the first sign of carcinomatous meningitis from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [12]. Dawoud et al. (2021) describe a case of transient oculomotor nerve palsy in a pregnant woman with a cavernous sinus meningioma, highlighting the potential role of hormonal influences on tumor growth [13]. Simón et al. (2024) discuss recurrent VI cranial nerve palsy secondary to idiopathic cavernous sinus pachymeningitis, illustrating the importance of considering the cavernous sinus’s inflammatory conditions [14]. Finally, Kumarasiri et al. (2022) present a case of bilateral ptosis in a child with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), demonstrating that demyelinating diseases can also affect the oculomotor nerve [15]. Elavarasi & Goyal (2018) discuss a case of brainstem tuberculoma, highlighting the potential for delayed complications in TBM [16].

In summary, oculomotor nerve palsy in the setting of meningitis raises a complex differential diagnosis. While bacterial meningitis, including N. meningitidis and TBM, is a significant consideration, other infectious, inflammatory, and neoplastic processes must also be considered. A thorough clinical evaluation, neuroimaging studies, and CSF analysis are crucial for establishing the correct diagnosis and guiding appropriate management.