Jane Goodall always remembered the first time a wild chimpanzee took a banana from her outstretched hand.

PREMIUM Jane Goodall, Who Studied Chimpanzee Behavior for Decades in Africa, Dies at 91

PREMIUM Jane Goodall, Who Studied Chimpanzee Behavior for Decades in Africa, Dies at 91

In that moment, she would often say, the chimp—a grizzled male she had dubbed David Greybeard—welcomed her into a community of humanity’s closest living relatives. It opened a relationship with wildlings that in due course upended scientific misconceptions about chimpanzees and turned her into a global icon of conservation.

As an untrained young woman in the summer of 1960, she first ventured into the forests of what is now Gombe National Park near Lake Tanganyika in Tanzania to study chimpanzees, equipped with little more than a notebook, a pair of binoculars and almost infinite patience. For five months, though, the wary creatures evaded her. In fact, no one had ever been able to study them at close hand.

By winning Greybeard’s trust, she gained entry to the troop of wild chimps that became the focus of her life’s work. “The chimps had accepted me. And gradually I was able to penetrate further and further into a magic world that no human had ever explored before: The world of the wild chimpanzees,” she said in a 2017 documentary.

Goodall died Wednesday in California, according to a social-media post by the Jane Goodall Institute. She was 91 years old.

She was born April 3, 1934, in London, the daughter of a businessman and a novelist. Her mother, who accompanied her on her first expedition in Africa, wrote under the name Vanne Morris-Goodall. From an early age, Goodall immersed herself in storybooks about wild creatures, vowing to one day visit Africa where, like Dr. Dolittle or Tarzan, she might learn to talk to animals. When a childhood friend invited her to visit her farm in Kenya, she quickly accepted, saving her waitress wages to pay the fare.

“At the time, I wanted to do the things which men did and women didn’t. You know, going to Africa, living with animals. That’s all I ever thought about,” she said. “Everything led in the most natural way, it seems now, to that magical invitation to Africa.”

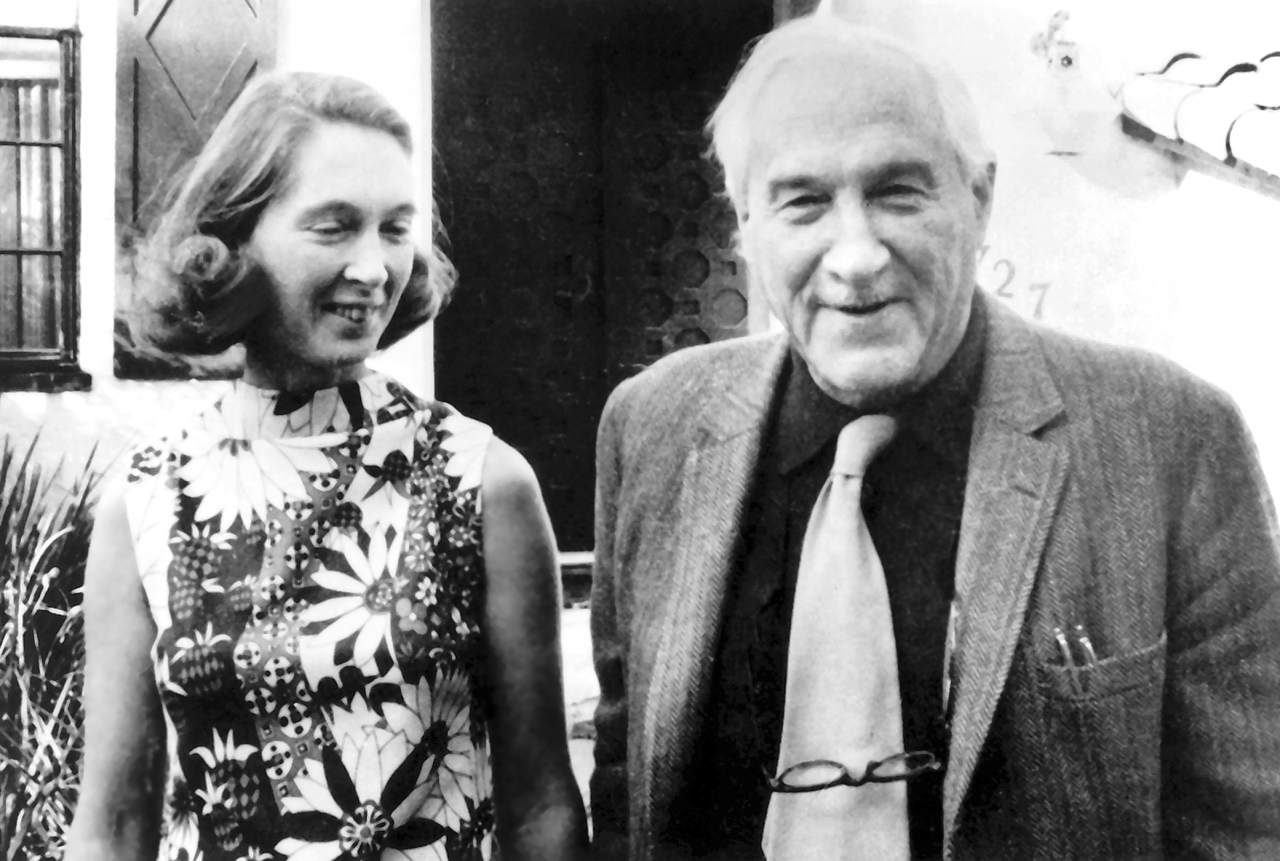

Goodall with her mentor Louis Leakey.

There, she met the renowned paleontologist Louis Leakey, who had discovered some of the first known fossils of ancestral human species. He eventually hired her as his secretary and, although she had no training in animal science, sent her to study the chimpanzees at Gombe in the hope their way of life might offer insights into early human behavior.

“At that time in the early 1960s, it was held at least by many scientists that only humans had minds,” she said. “Only humans were capable of rational thought. Fortunately I had not been to university and I did not know these things. I felt very much as though I was learning about fellow beings capable of joy and sorrow, fear and jealousy.”

Once in their confidence, she quickly discovered that chimpanzees like David Greybeard made and used tools, a talent then considered uniquely human. Her revelation rocked the research world. “My observations at Gombe would challenge human uniqueness and whenever that happens there is always a violent uproar,” she said. Inspired by her meticulous fieldwork, scientists have since cataloged at least 10 primate species of monkeys and apes and 30 species of birds, thought to use sticks, rocks or leaves as tools. Goodall also discovered chimps had lasting relationships between family members that extended beyond mother-infant bonds.

She learned, too, that chimpanzees weren’t vegetarians, as animal experts had believed, but avid meat-eaters. She was dismayed to discover that these chimps also were capable of warfare, infanticide and cannibalism. “I thought they were like us, but nicer than us,” she said. “Then suddenly we found that chimpanzees could be brutal—that they, like us, had a darker side to their nature.” Her findings revolutionized primatology, and laid the foundation for other women researchers, like Dian Fossey, to later take the lead in the field.

Although she had no undergraduate degree, Goodall was admitted for graduate study at Cambridge University, where in 1966 she received a doctorate in animal behavior.

Goodall in a 1965 CBS television special.Goodall observing a field of African baboons in 1974.

In 1971, she published the first of what would become more than two dozen nonfiction books and children’s books. She withdrew from publication a 2013 book with a co-author when the Washington Post called attention to a dozen passages that had been plagiarized. She apologized, revised and reissued it with 57 additional pages of endnotes.

In 1975, armed rebels working to overthrow the Tanzanian government attacked her field camp and kidnapped three Stanford University students and a Dutch camp assistant, while she and others eluded capture by hiding in the jungle. Their families eventually raised nearly $500,000 to ransom the hostages, according to news accounts.

She established the Jane Goodall Institute in 1977 to continue her research. In 1991, she organized a youth service program called Jane Goodall’s Roots & Shoots that is active in more than 60 countries.

In recent years, she devoted much of her time to activism and charity work surrounding conservation issues, animal rights and endangered primates and climate change. In April 2002, Goodall was named a United Nations Messenger of Peace. She was made a Dame of the British Empire in 2004 and awarded the Legion of Honor by France in 2006. In 2021, she received the $1.4 million Templeton Prize, the latest among many science, conservation and communication awards. She was given honorary degrees from more than 50 universities, and her work has been the subject of numerous films and television documentaries.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, Goodall traveled more than 300 days a year. Despite pandemic-related challenges, she remained connected to worldwide audiences from her home in Bournemouth through remote lectures and her podcast, “The Jane Goodall Hopecast,” which launched in 2022.

In a 2010 Wall Street Journal essay reflecting on her life as a researcher and activist, she described her wonder at the sight of chimps at play in a waterfall as a balm for her prosaic public appearance engagements.

“I get the same deep satisfaction when I am alone in the forest, in the dim green and brown world beneath the great trees. A sense of timelessness. A feeling of peace that I take away with me, that sustains me during my days of lectures, meetings, hotels and airports, the noise of traffic, people talking loudly in receptions.”

“Sometimes we must leave what we love to save it,” she wrote.

Jane Goodall, Who Studied Chimpanzee Behavior for Decades in Africa, Dies at 91

Jane Goodall, Who Studied Chimpanzee Behavior for Decades in Africa, Dies at 91  Jane Goodall, Who Studied Chimpanzee Behavior for Decades in Africa, Dies at 91

Jane Goodall, Who Studied Chimpanzee Behavior for Decades in Africa, Dies at 91  Jane Goodall, Who Studied Chimpanzee Behavior for Decades in Africa, Dies at 91

Jane Goodall, Who Studied Chimpanzee Behavior for Decades in Africa, Dies at 91