NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has detected a molecule on a distant Brown Dwarf star formerly believed to be an indicator of life. Called phosphine, the discovery of this molecule in a star now casts doubt on its usefulness as a biomarker on other planets and moons like Venus.

Phosphine is a molecule that contains a single phosphorus atom and three hydrogen atoms. Pure phosphine is odourless, although most commercially available grades have the odour of garlic or decaying fish.

It is highly flammable and can be very explosive when exposed to air. On Earth, it’s made only by life (or synthesized in industrial chemistry), leading many to believe its presence on distant worlds must mean life, in some form, likely exists there.

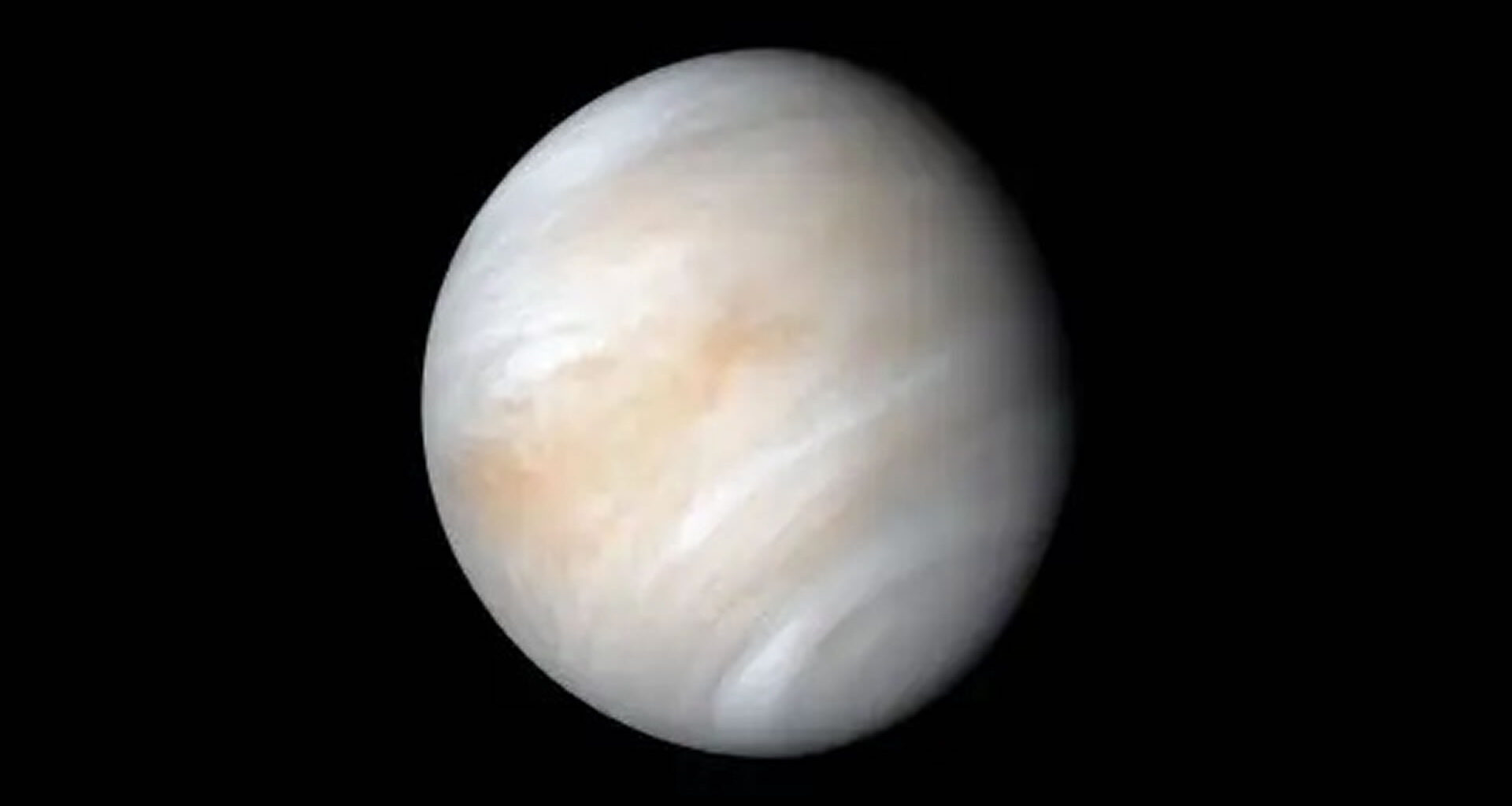

In 2020, some scientists thought they’d spotted it in Venus’ atmosphere. This was a surprise, as it should break down quickly, so if it was there, something must be constantly replenishing it.

This led to some scientists speculating that something, perhaps lifeforms, was producing it. However, we already know that phosphine has also been detected on Jupiter and Saturn through non-biological chemistry deep in their atmospheres.

Phosphine was found on a distant brown dwarf

For this reason, among others, phosphine shouldn’t automatically be considered a “life signal.”

Brown dwarfs are considered to be “failed stars” that are too small to ignite regular hydrogen fusion, but are bigger than planets. Instead, these diminutive stars fuse a little deuterium (a heavy hydrogen isotope) when young, but that fizzles out.

Because of this, they glow dimly (the surface of the youngest and largest can reach up to 3,632°F/2,000°C), mostly in infrared, so telescopes like JWST are perfect for studying them. Inside them, hot gas churns in convection loops, moving chemicals around their atmospheres.

So what is going on here? Well, some models predict that brown dwarfs and “hot Jupiters” (giant exoplanets) should sometimes have phosphine.

To see if this model holds water, JWST looked at 23 brown dwarfs between 100–700 °C with no phosphine detected. Now, unexpectedly, JWST has detected phosphine on Wolf 1130C (a 608°F/320 °C brown dwarf).

This obviously raises the question of why this one, and not the others? Astrophysicists are currently stumped, but one idea is that Wolf 1130C is very old and metal-poor, which might change its internal chemistry.

Casts doubt on Venus’ lifeforms

If phosphine shows up in weird, hostile places like brown dwarfs (where life is impossible), then it’s clearly not a clean biosignature. Critically, this discovery now casts serious doubt on claims of Venus’ “life” claim.

It is more likely that the phosphine (if it was really there) came from strange atmospheric chemistry we don’t yet understand, not microbes. The bottom line from this discovery is that phosphine is unreliable as a sign of alien life.

That is, until we can, at the very least, understand the chemistry across different environments. The discovery of phosphine on a brown dwarf makes it clear we don’t yet know all the ways this molecule can form in extreme environments.

Until the chemistry is nailed down, phosphine can’t be trusted as a smoking gun for life.

The study has been published in the journal Science.