Most fluorescent imaging relies on dyes that emit blue or green light. These imaging agents work well in cells, but they are less useful in tissue because the low levels of blue and green fluorescence produced by the body interfere with the signal. Blue and green light also scatter in tissue, limiting their ability to penetrate deeply.

Red-emitting dyes offer more explicit images for deep-tissue imaging, but they’ve long been hindered by poor brightness and instability. Most red dyes have low quantum yields; only about 1% of the absorbed light is re-emitted as fluorescence, making them dim and unreliable.

Achieving efficient red and near-infrared (NIR) emission in boron cation-based emitters remains challenging owing to their intrinsic instability, strong electrophilicity of the boron centre, and pronounced non-radiative decay governed by the energy gap law.

Now, MIT chemists have designed a new type of fluorescent molecule based on a borenium ion, a positively charged form of boron that can emit light in the red to near-infrared range. Until recently, these ions have been too unstable to be used for imaging or other biomedical applications.

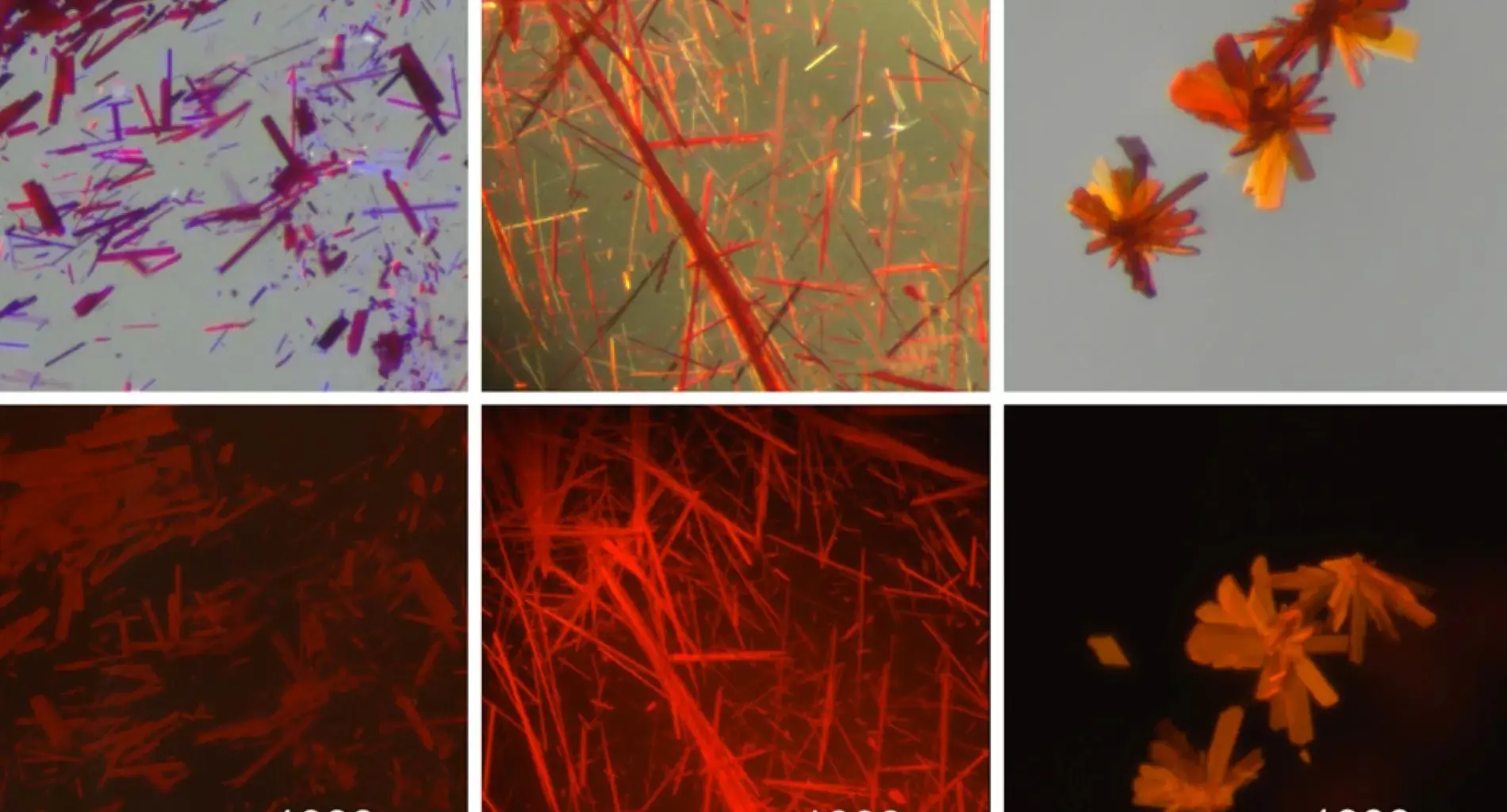

In a study appearing today in Nature Chemistry, the researchers showed that they could stabilize borenium ions by attaching them to a ligand. This approach enabled them to create boron-containing films, powders, and crystals, all of which emit and absorb light in the red and near-infrared ranges.

That is important because near-IR light is easier to see when imaging structures deep within tissues, which could allow for more explicit images of tumors and other structures in the body.

In the new study, researchers began experimenting with the anions (negatively charged ions) that are a part of the CDC-borenium compounds. Interactions between these anions and the borenium cation generate a phenomenon known as exciton coupling, the researchers discovered. This coupling, they found, shifted the molecules’ emission and absorption properties toward the infrared end of the color spectrum. These molecules also exhibited a high quantum yield, enabling them to emit light more efficiently.

“Not only are we in the correct region, but the efficiency of the molecules is also very suitable,” Gilliard says. “We’re up to percentages in the thirties for the quantum yields in the red region, which is considered to be high for that region of the electromagnetic spectrum.”

The researchers also demonstrated that they could convert their borenium-containing compounds into various states, including solid crystals, films, powders, and colloidal suspensions.

For biomedical imaging, Gilliard envisions that these borenium-containing materials could be encapsulated in polymers, allowing them to be injected into the body to use as an imaging dye. As a first step, his lab plans to work with researchers in the chemistry department at MIT and at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard to explore the potential of imaging these materials within cells.

Because of their temperature responsiveness, these materials could also be deployed as temperature sensors, for example, to monitor whether drugs or vaccines have been exposed to temperatures that are too high or too low during shipping.

“For any type of application where temperature tracking is important, these types of ‘molecular thermometers’ can be beneficial,” Gilliard says.

“If incorporated into thin films, these molecules could also be useful as organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), particularly in new types of materials such as flexible screens,” Gilliard says.

“The very high quantum yields achieved in the near-IR, combined with the excellent environmental stability, make this class of compounds extremely interesting for biological applications,” says Frieder Jaekle, a professor of chemistry at Rutgers University, who was not involved in the study.

“Besides the obvious utility in bioimaging, the strong and tunable near-IR emission also makes these new fluorophores very appealing as smart materials for anticounterfeiting, sensors, switches, and advanced optoelectronic devices.”

In addition to exploring possible applications for these dyes, the researchers are now working on extending their color emission further into the near-infrared region, which they hope to achieve by incorporating additional boron atoms. Those extra boron atoms could make the molecules less stable, so the researchers are also working on new types of carbodicarbenes to help stabilize them.

Journal Reference:

Deng, CL., Tra, B.Y.E., Zhang, X. et al. Unlocking red-to-near-infrared luminescence via ion-pair assembly in carbodicarbene borenium ions. Nat. Chem. (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41557-025-01941-6