Bearded vultures. Image in Creative Commons.

Bearded vultures. Image in Creative Commons.

Bearded vultures (Gypaetus barbatus) are breathtaking creatures. With a wingspan of nearly 9 feet (2.75 meters), they’re among Europe’s largest — and rarest — birds of prey. They’re also among the most eccentric: they stain their feathers with red mud, dine almost exclusively on bone, and reuse the same cliffside nests; sometimes, for centuries.

Through this habit, these magnificent, bone-eating birds have unintentionally created time capsules. They’ve created a “museum” of the biocultural record of the people and ecosystems they once shared the mountain with.

Time Capsules in a Nest

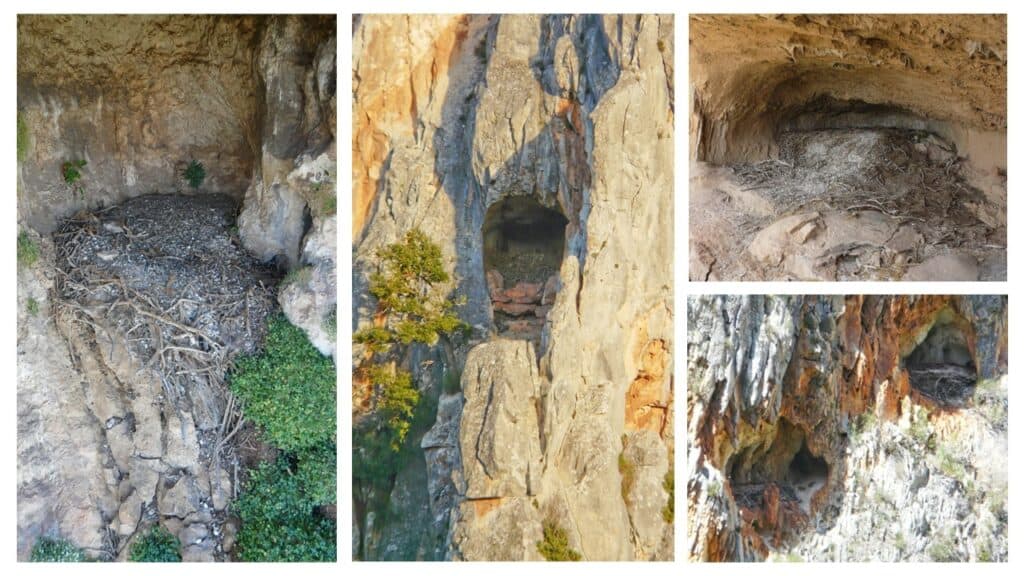

Although bearded vultures disappeared from southern Spain nearly a century ago, their nests still cling to the cliffs of the Sierra Nevada, often in remote, treacherous spots. A team of archaeologists, led by Sergio Couto from the University of Granada’s Cultural Archaeology Laboratory (MEMOLab), set out to investigate what secrets these old nests might hold.

Finding them was no easy task. Some were hidden in caves hundreds of meters up sheer rock faces. Couto pored over 18th- and 19th-century explorers’ journals and black-and-white photographs. He also visited nearby villages, speaking to elders in their 70s and 80s who remembered tales of the bearded vultures and their eerie nests.

Some of the nests. Image credits: Sergio Couto.

Some of the nests. Image credits: Sergio Couto.

It wasn’t easy. But in the end, he managed to piece together a puzzle with 12 of these nests. Couto and colleagues took them into the lab and analyzed them layer by layer to see what was preserved. The results were stunning.

In total, they recovered and cataloged 2,483 distinct items. The vast majority, as expected, were related to the vultures’ diet — over 2,100 bone remains from wild and domestic ungulates, telling a story of the region’s historical fauna. But nearly 10% of the items were something else entirely: they were man-made.

The birds, it turns out, aren’t picky decorators.

Lost and Found

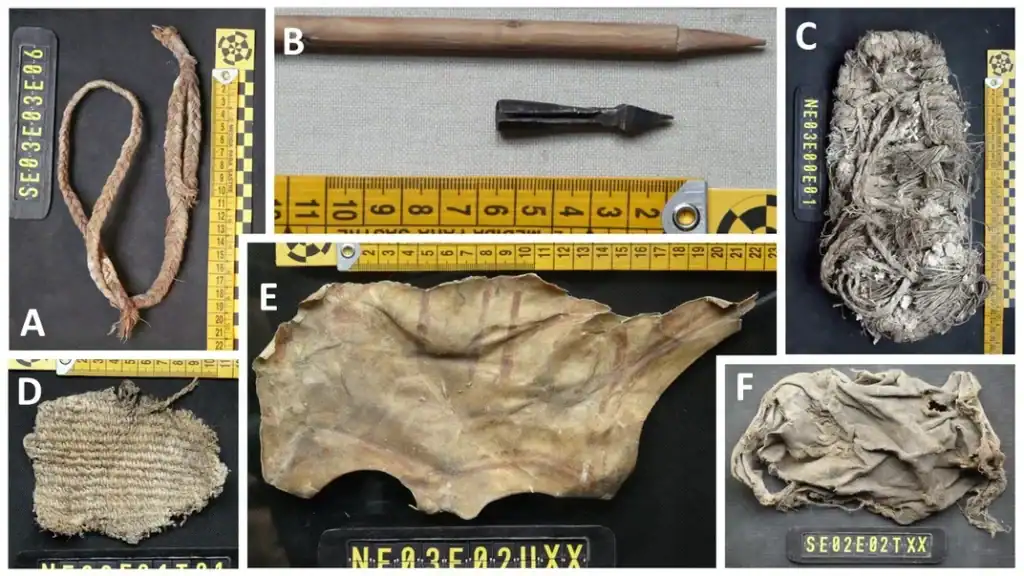

Just some of the recovered objects, including bits of rope, a crossbow bolt, a slingshot, and bits of leather. Image credits: Sergio Couto.

Just some of the recovered objects, including bits of rope, a crossbow bolt, a slingshot, and bits of leather. Image credits: Sergio Couto.

For centuries, the vultures had been picking up the lost, discarded, and forgotten remnants of human activity from the mountain slopes and carrying them home. These items were likely used to soften the nest bowl for incubation, a behavior observed in modern vultures.

The collection reads like a catalog from a lost-and-found spanning half a millennium. The scientists unearthed 129 pieces of cloth, 72 scraps of leather, and dozens of items woven from esparto grass, a tough, fibrous plant ubiquitous in the region. Among the esparto artifacts were ropes, basketry fragments, and even part of a slingshot.

Artifacts Among the Nests

Still, a couple of items really stood out. The first was a crossbow bolt: a short, iron-tipped arrow designed for a powerful medieval weapon. The researchers speculate the vulture may have scavenged it from the carcass of an animal hunted by a human, or perhaps simply picked it up as a curiosity, mistaking the wooden shaft for a branch to add to its nest structure. Then there were the shoes.

In one nest, they found an agobia, a type of rough, disposable footwear woven from grass and twigs, meant to last only a few days of hard mountain travel. The existence of these items was thrilling, especially when the results for carbon dating came back. The shoes, it turns out, were around 674 years old. This single bird’s nest contained an artifact dropped by someone walking through the Sierra Nevada mountains during the time of the Kingdom of Granada, when much of Europe was steeped in the High Middle Ages.

Most uncovered objects were of animal nature: bones, hooves and even a few eggshell fragments. Image credits: Sergio Couto.

Most uncovered objects were of animal nature: bones, hooves and even a few eggshell fragments. Image credits: Sergio Couto.

A Taphonomic Agent

Bearded vultures often nest in cool, dark caves. These caves have dry microclimates which are perfect for preserving artifacts.

This is valuable from multiple perspectives. From an ecological perspective, the thousands of bone fragments provide a long-term dietary record, offering a baseline of what these vultures ate for centuries. By identifying the bones, scientists can reconstruct the historical abundance of both wild prey, like ibex, and domestic livestock, like sheep and goats, painting a picture of past environments and human-animal interactions.

Furthermore, the eggshell fragments found in the nests offer a chance to conduct toxicological studies. By comparing historical shells to modern samples, researchers may be able to pinpoint the impact of pesticides and other pollutants, potentially uncovering the precise environmental triggers that led to the vulture’s local extinction.

From an archaeological and ethnobiological standpoint, the nests are “natural museums”.

The man-made artifacts are a direct link to the material culture of the people (likely shepherds, farmers, and hunters) who inhabited these remote mountain areas. The woven esparto items, for example, connect to a rich tradition of plant-fiber technology in the Iberian Peninsula that dates back thousands of years to the first farming communities. Similar artifacts have been found in nearby Neolithic caves. These lost and found objects, preserved by a bird, offer a glimpse into the daily lives of common people whose stories are rarely written down.

The vulture, in this sense, becomes what scientists call a “taphonomic agent”—an organism that alters the archaeological record, in this case by collecting and curating it in the most unlikely of places.

Ancient Records for Modern Conservation

But most importantly, this has profound implications for modern conservation. The Bearded Vulture is the focus of major reintroduction efforts across Europe, and this research provides a treasure trove of data to guide those projects.

By understanding the species’ historical diet and nesting habitat, conservationists can better select suitable release sites and prioritize which habitats to protect. It provides a blueprint for what a thriving Bearded Vulture population needs, based on centuries of accumulated evidence.

Who would have thought you could get all this from the nests of vultures?

Journal Reference: Margalida, A., Couto, S., Pinedo, SO, Gil-Sánchez, JM, Agudo Pérez, L., Marín-Arroyo, AB 2025. The Bearded Vulture as an accumulator of historical remains: Insights for future ecological and biocultural studies . Ecology 106: e70191.