I used to go to the movies with Chris Knox. It was not just us. We were two members of a band of Auckland film reviewers in the 1990s and 2000s, watching previews in small screening theatres and gorging on a fortnight of free tickets during the film festival in mid-winter. They were good times. I wonder if that reviewing circuit still exists.

The point is that Knox and I both caught a Lou Reed documentary at the festival one year and as we waited for the bus back to Grey Lynn, he launched into a minor rant about the movie we had just seen. It was far too nice. Adulatory, even. Where was the dark side? Sure, Reed had been a genius but he could also be a real asshole. Knox saw the same thing happen to John Lennon, who was being venerated as a saintly figure. People stood up and wept at the end of a Lennon documentary, for goodness sake. Writing beautiful songs did not mean you were automatically a wonderful human being.

Knox was pretty good to me, even though I was gently reprimanded during that bus trip after admitting I owned Metal Machine Music on CD when the entire point of Metal Machine Music is you play it on vinyl. I didn’t take it personally. But I knew he could be caustic, abrasive, sarcastic, judgmental with others – maybe even a bully, as Craig Robertson says in his impressive, balanced, insightful and exhaustive new biography of Knox, Not Given Lightly. Knox’s close friend and musical collaborator Alec Bathgate told Robertson he must be honest and that Knox would like the unflattering stuff to be included. The movie critic who wanted a warts-and-all portrait of Lou Reed would approve.

So we get plenty of examples of Knox being rude. He was rude to two of pop music’s nice guys, Michael Hutchence and Jordan Luck. He was rude to Dudes-era Dave Dobbyn after Dobbyn was complimentary to him. He was rude when he wrote a song about Martin Phillipps, titled “Self-Deluded Dreamboy (in a Mess)”, and then asked Phillipps and David Kilgour to sing it with him (Kilgour told him to fuck off). The Fall’s Karl Burns punched him in the face and by all accounts Henry Rollins nearly did the same. It might have seemed like punk rock was the perfect vehicle for his performative antagonism but he was more inspired by the radical honesty of Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band, with all its painful self-reflection. That meant Knox was rude about himself too. But the fact is he was always pretty funny with it.

Knox was a complicated figure. Did his abrasiveness hide a more compassionate centre or at least co-exist with it? That seems obvious. If I had to pick a favourite Knox song, I would go for “The Slide” from the Tall Dwarfs EP Dogma. It’s melodic and sincere with a very nice vocal performance by Knox (it was later covered by both Strawpeople and Shayne Carter). This is a song about assisted dying that is not, despite the EP’s title, dogmatic. Instead, it is deeply sympathetic to the human predicament, the basic fact of being stuck in a failing body for a duration of time. “Let her decide,” he crooned in 1987, more than 30 years before anyone could legally decide.

The same EP has a track I always thought of as a mirror to “The Slide”. On “Lurlene Bayliss”, Knox narrates the journey of a woman who caught the bus to town to get an injection of medication. She becomes lost and confused, tries to buy a children’s toy – a My Little Pony – but finds the city has changed around her and is unrecognisable. Other people might mock a character like that, but not Knox. And although the rapidly changing Auckland of the mid-80s was the setting, Robertson reveals the inspiration was a woman Knox met on a bus trip in Christchurch, between Bathgate’s house and Nightshift Studios, where Dogma was recorded. Another inspiration I had not picked up on was John Cale’s narration in the Velvet Underground’s “The Gift”, in which lonesome Waldo Jeffers mails himself to his girlfriend. That story was black comedy with a shock ending but Knox’s was poignant and then, ultimately, liberating.

Those songs, and the general arc of Tall Dwarfs’ work during the 1980s, revealed a new honesty and directness that led naturally to Knox’s relatively naked, open solo album Seizure, which contained the famous love song that almost predictably gives Robertson’s book its title. Knox took a line about “love not given lightly” from the Velvet Underground, turning something seedy and transgressive into the hook for a sentimental, self-deprecating tribute to his partner and the mother of his children. Again it was funny, very Kiwi and even wholesome, despite Knox’s alternative status and its origins in a song about sado-masochism. That album and the ones that followed contained songs of radical self-examination and empathy.

Chris Knox recording Slugbuckethairybreathmonster, Hakanoa Street, 1984. Photograph by Alec Bathgate, private collection.

Chris Knox recording Slugbuckethairybreathmonster, Hakanoa Street, 1984. Photograph by Alec Bathgate, private collection.

Knox’s musical career peaked in the early-mid 90s. He released seven albums, some by the Tall Dwarfs and some solo, between 1989 and 1995, as well as drawing a weekly Herald cartoon (the much-missed Max Media) and producing TV animation and film reviews. By then he was earning enough to get off the sickness benefit and provided an example of how an artist might pursue both a career and a family life in New Zealand. There was a well-received American tour and US critics came up with some of the sharpest descriptions of what Knox was up to, musically. “Knox’s stage shtick is part Brechtian theatre, part Robin Williams routine, and even when he goes off the deep end into awkward vaudeville the warmth behind his gooey sentiments and Liverpudlian la-la-las manages to shine on,” Mike Rubin wrote in the Village Voice. The same publication said the Tall Dwarfs “conjure up a universe where Syd Barrett or Marc Bolan was the fifth Beatle”.

By the 2000s, Knox and the Tall Dwarfs were selling fewer records, but then so was everyone. More of Knox’s time was spent on the kind of media work that had originally been enabled by his alternative credibility, and he did so without losing one iota of that credibility. You could say he had more fame, but less of it was because of music. He was making a warm and enjoyable TV show called New Artland when he suffered a severe stroke in 2009. There have been no more cartoons, albums, reviews or tours since, but there has been the odd live appearance, including an inspirational, even ecstatic performance at the Laneway festival in 2010, captured in the recent Shayne Carter doco, Life in One Chord. He also paints, Robertson tells us, but with his left hand.

The stroke meant Robertson also had to change course. His initial idea for a book was a kind of social or cultural history in which Knox’s journey from the post-hippie underground of Dunedin in the 1970s to the mass-media mainstream in the 2000s illustrated New Zealand’s own trajectory. Who changed: Knox or the world around him? I guess the answer is both did. Anyway, it must have become clear after 2009 that a full biography of Knox was not just a good idea but an essential one. While Knox could not be interviewed, he seems to have kept everything he ever produced. And Robertson got on with talking to the people who knew him.

Robertson was perfectly placed as a fan and admirer who was not too close. Based in Boston, he is a media studies professor, but he grew up in Dunedin, did his BA (Hons) essay at the University of Otago on the so-called Dunedin Sound, and edited a fanzine called Side On, named after a Clean song. His brother Grant recently published a book named after a different Clean song.

There must have been some trepidation. Knox did so much, was so influential and remains so loved by so many that any biography faces high expectations. Robertson has met them. This is a book written and produced with great care and respect. You could even say it is the most important and thorough music biography ever published in New Zealand, and it makes an excellent companion to Matthew Goody’s Flying Nun history, Needles and Plastic, from the same publisher. We can now agree that the Flying Nun story has been well and truly told.

The Flying Nun story would have happened without Knox of course but it would have been narrower, less interesting and limited to the South Island. Besides setting a standard with his own music, Knox recruited bands, distributed records (in person), supervised pressings, shot some of the videos and even drew the advertisements in Rip It Up that were part of the image of the label. Without Knox, there would have been less emphasis on the philosophy behind recording techniques and the general demystification of the process. He brought his ethics to it. The strength of his personality and the firmness of his opinions meant Knox quickly became the face of the label.

Traces of Robertson’s more academic ideas about the social and cultural history of New Zealand remain in Not Given Lightly, but they are unobtrusive. Besides, it is inevitable that any discussion of Knox’s songs, cartoons and writing will situate him as a critic and observer of changing times, especially the slow evolution of Kiwi male attitudes. Knox’s feminism was in the self-critical, self-exposing tradition of Lennon (literally self-exposing: Knox used the nude John and Yoko photo as the invite to his 21st), and he was sorry on behalf of men long before David Cunliffe ever thought of it. He was horrified to observe the sex industry on a tour of the Netherlands and expressed his revulsion and anger at “the machinations of a woman-hating, woman-fearing industry” in one of his Listener columns. In another column, the national shock of the Aramoana shooting in 1990 became an opportunity, as it also was for Don McGlashan, to muse on the white male New Zealander’s insularity, dysfunction and inability to communicate. A Knox song from the same era, “Liberal Backlash Angst (the excuse)” expressed the dark fear that lay behind those violent male attitudes. He was not writing from a sense of superiority but from an understanding of his own flaws and a knowledge that he too was a work in progress. It is touching to learn that he set about becoming a better person in middle age and that he was surprised some people had been genuinely hurt by what he thought was banter and constructive criticism.

Had things gone differently, Knox might have written his own story. A Knox memoir must remain one of the great what-ifs. His voice was funny, vivid and idiosyncratic and we don’t get enough of that voice in Not Given Lightly, particularly in connection to what seems like a fairly happy, conservative, middle-class childhood in Invercargill. It is hard to fully comprehend the switch from that younger, nerdier Knox to the one we all know without the interiority a memoir, or even long reflective interviews, might have provided. But it is intriguing to learn that the value of honest communication was one positive thing he thought he took from his Christian upbringing. That honesty, Robertson argues, was at the heart of Knox’s creativity.

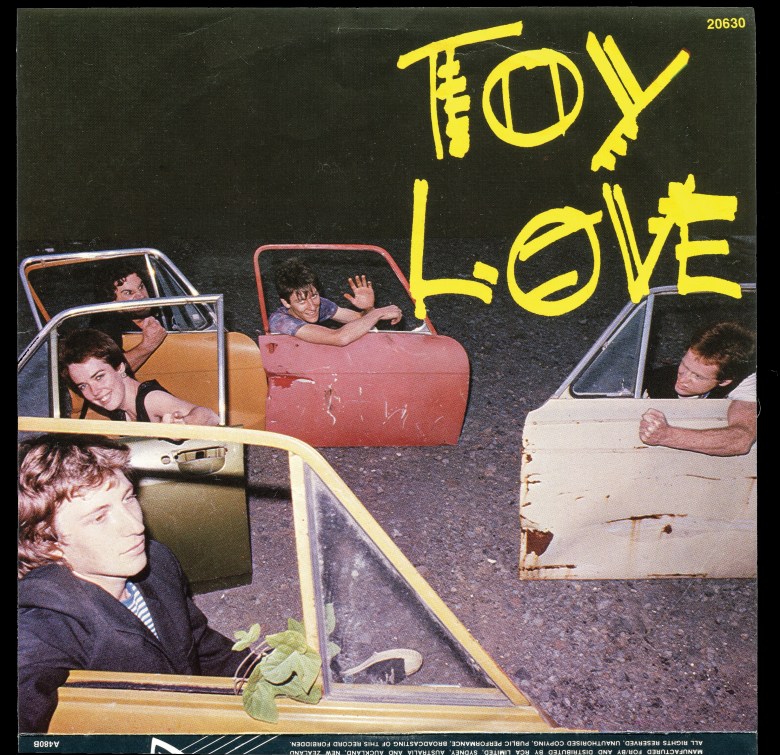

Poster for Toy Love 7 EP released by Deluxe, May 1980. Photo: Phillip Peacocke, private collection.

Poster for Toy Love 7 EP released by Deluxe, May 1980. Photo: Phillip Peacocke, private collection.

He was still at high school when he sent poems to the underground magazine Earwig. One of them revealed a sensitivity about the same kind of marginal or overlooked figure who inspired “Lurlene Bayliss” more than two decades later. That sensibility must have always been central. It is there in the first Tall Dwarfs single, “Nothing’s Going to Happen”, parts of which read like a manifesto inspired by a 60s, Lennon-ish view of art and freedom, and the urge to rebel against the narrowness of education:

Maybe all the children in small rooms

Will fall silent at a wall or window

And forget to breathe for just one minute

Because of some beauty that has not

Been altered, damned or pointed out

By the clumsy dark oafs who train them

That is the Knox voice. Sometimes the straightness and seriousness of Robertson’s historical account contrasts with the intensity of Knox’s version. For example, this is how Robertson describes what it was like for Knox to see a band whose music he loved:

“More than the difference between record and concert sound, Knox was transfixed by the embodied performance of songs he knew so well from records, of seeing the singers and musicians whose immediacy on record had captivated him.”

Compare that to how Knox himself described one of those moments, which was seeing Lou Reed perform “Heroin” at the Christchurch Town Hall in 1974:

“He sings it low and so so slow with aching pauses as he winds the mic cable round and round his straining arm and you could swear he’s going to shoot up or has he already? It’s very difficult to tell. His body’s a mess, shaking and out of time, sweating, nor is he moving to the music, just crashing into the mic and fumbling through the almost sacred words.”

That is not to criticise Not Given Lightly or the biographical approach in general, which must by definition stand back and affect a kind of informed neutrality. Among other things, Robertson is very good on the music, and has given us the Toy Love book that has long demanded to be written, as well as the Tall Dwarfs book and the Knox book. The Toy Love story is one of massive promise and potential, crushed by the squalid and merciless industry, as Knox saw it, not entirely unfairly. Our greatest punk or new wave band of that era was reduced to living on potato fritters in Sydney and playing to disinterested crowds, while a major label made a mess of their record. It is almost a founding myth of New Zealand music history, and one that utterly changed how Knox saw things. We can call it a New Zealand trope, the band that deserved to make it. See also: Straitjacket Fits, Shihad.

Besides the text, it is valuable to have so much of the visual ephemera here as well: the gig posters, the cover art, the cartoons and drawings, the photos, the hilarious comic strip about a Dunedin acid trip. You could even say the book completes Knox’s own creative project, cut short in 2009, which was to turn his entire life into art, or to erase the thin borders between life and art. It was a project that started long before punk‘s arrival in 1977 finally provided the 25-year-old Knox with a proper outlet for being “scary and weird”, as Robertson puts it.

One last thing remains unexplained, though, and that is the Nothing. What did Knox mean by the mysterious idea of the Nothing? Was it theological? Unlikely. Philosophical? Maybe. The Nothing made a few appearances at intervals in the story of his life, like the monolith in 2001. It seems important. We learn that in 1974, Knox and Doug Hood left Dunedin on a road trip in Hood’s hippie VW in search of the Nothing. Knox kept a journal on that trip, “The Book of Nothing”. He wrote that the idea was to find and maybe even possess “the essence of NOTHING”. They failed, but at times they teetered on the brink of Nothing – both in its positive and negative forms.

Nothing later became the name of Hood’s black panel van and then appeared in the title of one of the Tall Dwarfs’ first and best songs. In 1984, they paired a new version of “Nothing’s Going to Happen” with “Nothing’s Going to Stop it”. The search for Nothing was revived many years later when Knox made two records with a band he dubbed Chris Knox and the Nothing. They were his last releases before his stroke. Is that meaningful? Robertson suspects the quest for Nothing came from taking acid and trying meditation rather than intensive reading of Sartre and Heidegger, or glimpsing something truly ineffable, but only Knox really knows.