(© Tom Wang – Adobe Stock)

Back in the days when people used to install software by inserting floppy disks into the slots on desktop computers, a few visionaries dreamt of being able to run software directly on the Internet and use it in the browser. As the twentieth century came to a close, now long-forgotten startups such as Desktop.com and myWebOS.com showed off technology that sought to overcome the constraints of the primitive browsers and low-bandwidth connectivity of the time. Their goal was to replicate the entire desktop experience of Windows or MacOS on the Web, and make the browser itself the operating system for web-based applications.

Two decades later, Josh Miller, who went on to found The Browser Company, which is nearing the final stages of being acquired by Atlassian, was looking at how his wife organized her work on a high-powered new computer as she started a new job:

I noticed, she never left Chrome. She’s in an old industry, the art world, but even the PDFs that she was working through, getting sent from the gallery or something, they would open as URLs. They’re really URLs. They weren’t really PDFs anymore. They’re in a browser. And she would do presentations, and even that was an app and a tab in her browser.

The decades-old dream had been realized, but not in the elegant, perfectly composed package that those early pioneers had envisaged. Instead, it had emerged as a random, disjointed side-effect of applications and content gradually migrating online over the years. The resulting browser experience was completely unsuited to what its users were trying to do, because it had never been designed with that use case in mind. Miller continues:

I was actually watching my wife, and just seeing this, and noticing that, okay, browsers were not invented to be used in the way my wife’s using them, which is really like an operating system. I don’t mean that in the technical sense, but they are where her apps and files were. They were now URLs, and it wasn’t designed for that.

A browser to get things done

This was what led Miller to go on to found The Browser Company of New York and launch its Arc browser, which has built up a passionate user base in the past few years. The aim was to create a browser that, instead of being optimized for browsing web pages, actually supports people who use their browser to get things done. He continues:

Our big goal was, ‘Hey, what would a browser look like if it was designed to make my wife be really happy to open her computer and really match what she does in it’ — which is work…

The core idea of Arc as a browser was really, it is where your apps and your files are. So for my wife’s job, how do you create a space that solves the tab problem for her, by keeping her organized and really organizing her tabs around what they really are — apps and the workflows around them — and deeply integrating with apps you use every day.

As an example, one of the most appreciated features in Arc is that the browser automatically sends the user a reminder five minutes before their next web meeting, including a button they can use to join the meeting without ever having to tab across and open their calendar. Then if, for example, they click away to another tab during a Google Meet meeting, Arc automatically pops it out into a picture-in-picture player so that it’s still visible to the side.

Right time

Miller is acutely conscious of the history and that many others have tried to do what he’s now attempting with Arc and its AI-centric successor, Dia. But he believes that he has a couple of advantages. The first is simply a matter of being in the right place at the right time:

This is not a new idea. Our theory is that the timing is right, right now. Because what didn’t happen in those [previous] eras [was], we didn’t have apps that were at URLs. We didn’t have files that were at URLs.

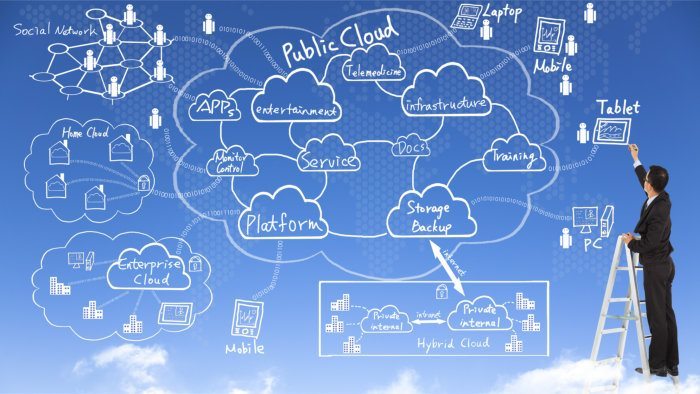

So the thing that has changed is, people tried to make a web-based operating system before anything in your operating system was on the Web. And now you look at the cloud graph, any cloud graph you want is like [going up] for the past 20 years. That has meant people’s stuff moving online. So that’s theory number one, is that, yes, it’s an old idea, but everyone else messed up the timing.

The second is a determination to meet people where they are rather than trying to force new behaviors on them. He explains:

A lot of people, like using Chromebooks, actually ask people to pretty profoundly change the way they do things for no reason other than a neat tech demo. People rarely articulate why a web-based operating system would be some big change other than, ‘Look, we can do it now!’ I think the thing that we observe in Arc, and in Dia we’re now trying to do, is say, ‘Don’t change anything.’

We actually just think, isn’t it kind of wild in 2025 you have all these tabs open, and they are so dumb, that they don’t know each other exist? We have the technology now to do stuff like that. So it’s much more about how do we intercept your existing browser and workflows to make it feel like more of an operating system? But actually not try to dramatically change how you get stuff done on your computer.

My take

The old adage that we overestimate what can happen in a year and underestimate what will happen in ten is played back here over a timescale of a quarter-century or more. As soon as the Web began to take off in the mid-1990s, people rushed to speculate how quickly computing would migrate online and make Windows PCs redundant. That hype cycle burst in the dot-com crash, and the ensuing slope of enlightenment has been so gradual that all those early ambitions were extinguished long ago.

Those early efforts were not all in vain, however. The team behind myWebOS.com made important contributions to the development of Ajax, one of the technologies that enabled more interactive web pages and early online applications such as Gmail and Google Maps. Many more technologies have evolved in the intervening years to support the sort of functionality we take for granted today in modern web applications like Canva and Figma.

Now here we are, 25 years later and computing has migrated online, just not according to plan. It’s up to a new generation to pick up the pieces and finally make sense of this brave new world.