“I wrote a story about the end of the world,” Stephen King says.

This will not surprise you. Doomsday is his business — along with the general unravelling of human beings, in society at large or in one small house in the woods.

The conceit in this particular story is that as one man’s life comes to an end, the entire world reaches its full stop. “There’s a word for that and I can’t remember what it is,” King says.

He’s at home in Maine in the study where he writes 1,200 words a day, six or seven days a week. Peering into it is like looking into the Ford factory in Michigan: out of here comes a product that dominates the culture.

“It is the idea that we all contain the world and the world disappears when we disappear,” he says and frowns. “There’s a word for that and I can’t f***ing remember what it is.”

I don’t know what it is either. But it reminds me of something that was said about Terry Pratchett when he was getting dementia: the mind that created the Discworld in 41 novels was foundering and with it an entire magical universe was coming to an end.

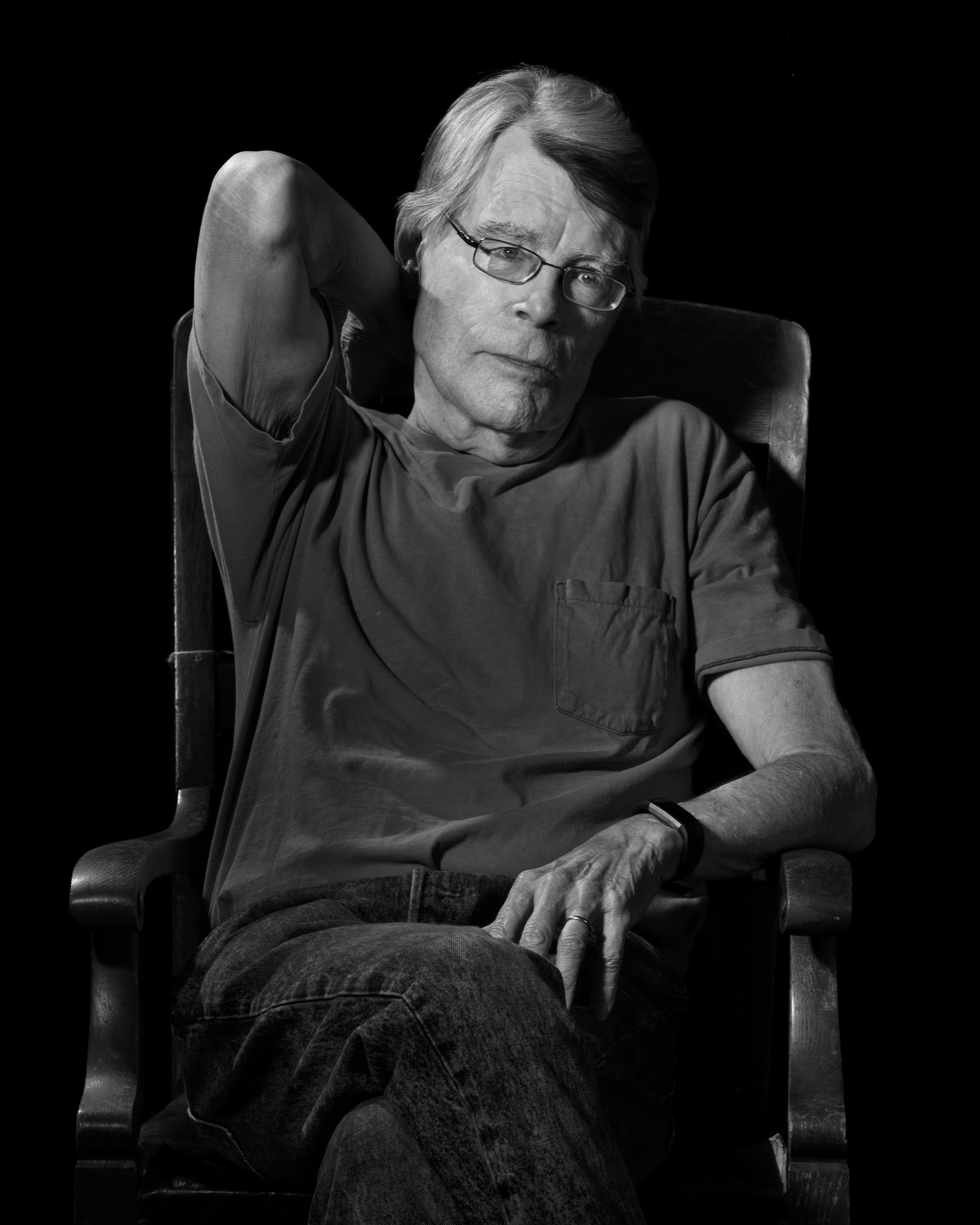

King writes 1,200 words a day, six or seven days a week

PHILIP MONTGOMERY/THE NEW YORK TIMES/REDUX/EYEVINE

“That’s what I’m afraid of,” says King, who has written more than 65 novels plus novellas and hundreds of short stories. “I’m afraid of that happening to me and every time that I can’t remember a word or something, I think, ‘This is the start.’”

King, 77, is wearing a black T-shirt from the 1995 Laconia Motorcycle Rally. His face is long and thin and his thick grey hair has a badger-like stripe of black down the middle.

He’s sitting in a large, tidy attic-like room, floored and panelled with orange-brown wood. You can buy a candle, believe it or not, called Stephen King’s Study (it’s unofficial merch and £16): it smells of oak and smoke and leather, and I expect it’s not far off, except that he no longer smokes but chews on a toothpick as we talk.

He recently finished a third novel in his Talisman series and is now on a temporary work halt, but when he is writing he writes in the mornings, seven days a week, interrupted only by the cleaning ladies who come on Mondays and Fridays.

“You want to keep it flowing,” he says. “You want to keep it fresh.”

His stories continue to go everywhere. The one about the world ending with one man (The Life of Chuck) has just been made into a film starring Tom Hiddleston. Two more adaptations will arrive in the next three months: The Long Walk, by the film-maker Francis Lawrence, the director of The Hunger Games, and The Running Man, an Edgar Wright film starring Glen Powell.

• What horror movies scare the directors Ari Aster, Edgar Wright and John Landis?

The Long Walk he wrote in college in 1969, to impress a girl. “Like, you know, if you read this book, maybe you’ll … just fall in love with me,” he says.

It imagines a dystopian America where 100 teenage boys volunteer for an annual race in which they walk continuously day and night, supervised by rolling trucks filled with soldiers. Anyone who falls below four miles an hour, after three warnings, is shot dead, until there is one left.

If someone slipped this to me in college, I’m not sure if I would fall in love so much as phone the police. Which is not to say it isn’t potent stuff. After I read it I started to dream about it.

King nods, pleased. “I want readers to feel just tense and totally carried away by the story,” he says.

He delivered it to his paramour in sections, “written on the back of whatever I had for paper, you know, like the syllabi from classes and stuff, because I didn’t have much money.”

King’s father “piled up all sorts of bills and then did a runout when I was two,” he wrote in his 2000 book On Writing, that is part memoir, part manual. He had a “herky-jerky” childhood, brought up with one older brother by a single mum. He went to school with kids “who wore the same neck dirt for months”. They sound like the characters in The Long Walk.

“The same sort of kids that are pulled into the war machine,” he says. As he wrote it, in college on a scholarship, young men were being drafted to Vietnam. His only condition for the film adaptation was that we see the teenagers being shot.

“If you look at these superhero movies, you’ll see … some supervillain who’s destroying whole city blocks but you never see any blood,” he says. “And man, that’s wrong. It’s almost, like, pornographic … I said, if you’re not going to show it, don’t bother. And so they made a pretty brutal movie.”

The idea for The Running Man came to him a few years later. By this time he was married to Tabitha and they were living in a trailer. Tabitha worked in a doughnut shop, King as a teacher. “I was thinking, ‘What would it be like if there was a game show where people got killed?’” he says. “You would have to presuppose a society that was kind of like Nineteen Eighty-Four, where you had blood and circuses.” During the February half-term break “there was a lot of snow, a lot of sleet, it was hard to go anywhere”. He wrote the entire thing that week and sent it to a science fiction publisher.

• Stephen King: 50 years of blood, guts and bestsellers

“I got my manuscript back with a little note that said, ‘We do not do books about dystopian societies.’”

So he put it in a drawer. Then Carrie (1974) and Salem’s Lot (1975), his first two published novels, did well. “The paperback publisher said, ‘What else do you have that we could do, maybe under a pseudonym?’” he says. They didn’t want to flood the market with Kings. So The Long Walk and The Running Man were published, in 1979 and 1982 respectively, under the name Richard Bachman.

The Running Man feels very contemporary, although it was written decades before the Hunger Games trilogy and the Korean drama Squid Game, which echo the idea of an impoverished populace being drafted into the arena.

Glen Powell in the film adaptation of The Running Man

PARAMOUNT PICTURES

“I must say I had a fun time thinking up [the] game shows,” King says. Competitors in The Running Man get a 12-hour head start before they are pursued by a team of hunters, like wanted criminals, and shot. But there is also Treadmill to Bucks, featuring people with heart problems running at a steadily faster pace while trying to answer questions.

“It was kind of amusing,” King says. “In a sick way. I mean, nobody said that I was a well puppy.”

I imagine your psychiatrist would have a few things to say about it, I say. “I’d never go to a psychiatrist. That would be … to pay somebody for the stuff that I can do.”

The other King book regarded as ahead of its time is The Dead Zone (1979), with its Bible salesman turned huckster politician Greg Stillson, who is the butt of jokes, holding bizarre but eye-catching rallies. The story’s hero, a clairvoyant, sees that he will be president one day. King, in turn, is credited with predicting Trump, although he is not sure that any book could have done this.

“If I wrote this in a book in 1965 … if it got published at all, it would be published as an allegory, like Animal Farm,” he says. “Nobody would have believed where we are today, with Gestapo agents in the street — they call themselves ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement], but they’re basically guys that are armed, they are wearing masks, they have huge amounts of money to spend and they are everywhere.”

• 25 years on, Stephen King’s memoir is still the best guide for writers

I ask if he ever pauses on social media, where he is a prolific Trump critic, to consider how many of his readers are Trump supporters. “I’m aware of it. There’s never been, you know, an organised boycott,” he says. “I feel I have an obligation to say what I think and be clear about it. It’s a question, like the song says, ‘Which side are you on?’”

A lot of liberal Americans now talk about future historians taking their side, presumably because they feel so disenfranchised by the present.

“There’s a story about the home run that was heard around the world,” King says. “There are … tens of thousands of people who will say, ‘I saw [the baseball player Bobby Thomson] hit that home run,’ and there were only, like, 5,000 people in the stands that day. So I think the opposite is true [with Trump]. Twenty or 30 years down the line, when I’ll be dead and you’ll be old, I think a lot of people are going to say, ‘Well, I never voted for Trump.’”

What about the other great story of our times, the rise of artificial intelligence?

“I don’t really care about AI,” he replies. “My sons [Owen King and Joe Hill] are both writers … and they’re all hot to trot about AI and how awful it is for writers.” (His other child, Naomi, looks rather better placed, as a Unitarian minister and yoga teacher.) “I just think that it’s a foregone conclusion that people are going to write better prose than some kind of automated intelligence.”

King with his wife, Tabitha, and son Owen in 2008

OLIVIER DOULIERY/ALAMY

So AI will never match a novelist, equipped with their own life experiences? “I didn’t say that. I think that once there is a kind of self-replicating intelligence, once it learns how to teach itself, in other words, it isn’t going to be a question of human input any more. It’s going to be able to do that itself. And then … have you ever read The Time Machine by HG Wells?”

In it, a Victorian scientist travels to the year 802,701, where he meets the Eloi, a childlike race frolicking in the ruins of human civilisation, while a subterranean species called the Morlocks work machinery and feed on the Eloi.

• Stephen King: Hurt a dog and you’ll regret it — even if it’s just in a book

“We’ll become the Eloi and AI will be the Morlocks and they’ll basically run everything,” King says. “Once you teach AI to write a novel, a good novel, it’s going to be a different ballgame. I like to think that I can stay ahead of AI in the time that I have left.”

Which brings us to the story of a universe disintegrating, with the end of one man named Chuck. King wrote it during the pandemic. “I didn’t think it was a particularly good story,” he says. “Then … I was in Boston to see a Red Sox game. I saw this guy across the street in front of Walmart and he had a couple of plastic buckets overturned and he was busking. And I thought, what if some guy came along and … started to dance to that? And then I thought, what if that guy was Chuck?”

The story runs backwards, from the end of Chuck and the end of the world, to this scene where Chuck dances and feels more alive than he has in years. “And it just went from there and it was a beautiful thing,” King says.

He beams, and thumps the table. “That’s what I live for, man!” he says.

“No sugar endings, no fairytale,” he says. “I gotta go and have dinner.”

It is nearly five o’clock. Time is coming for all of us. I fire a few last questions. What’s for dinner?

“I think some sort of chicken thing.”

Will he keep writing?

“I have at least one more book that I would like to write, and beyond that, man, I’m not going to say … I’d like to go out where people say, ‘I’d like another one.’”

Will he still write, even if he stops publishing?

• Read more film reviews, guides about what to watch and interviews

“I think that might happen. But I’m too old to do the JD Salinger thing and write four or five books that are in the desk drawer.”

So he’d put them out? Or leave them for someone else to publish?

“I don’t know,” he says. “It’s a creepy question.”

I feel this is rather rich coming from the chap who imagines children being shot to death because they can’t keep walking. But I don’t say so. I’m worrying we have not covered everything. There’s too much.

“That’s all right,” he says. “We do the best we can and f*** the rest.”

What’s your favourite Stephen King book? Let us know in the comments below