Summary

I simulate controlled outages to reveal hidden dependencies and harden recovery.

I use tc, namespaces, iptables/nftables and mock services; automate setup and teardown.

I plan scope, log everything, tune retries with jitter, and keep tests isolated from production.

When you run a home lab, it is easy to think everything works perfectly until something breaks. I wanted to see how my setup handled chaos, so I created controlled internet outages using Linux tools. The goal was to test my recovery procedures, alert systems, and overall network resilience. What I found was a mix of learning moments, avoidable mistakes, and some genuinely helpful discoveries that improved how I run my network.

Practicing recovery in a controlled scenario improved my response time and documentation.

It began as a harmless idea: to simulate brief service drops to ensure my automations could recover. Within hours, it grew into complete network isolation experiments that left parts of my lab unresponsive. I learned the hard way that simulated chaos needs careful planning and tight control. Still, the insights gained from those failures made it one of the most valuable experiments I have conducted in my home lab.

Why I simulated internet outages

The motivation and thesis for this experiment

I wanted a safe environment to explore how different services reacted to the loss of connectivity. For instance, my DNS server became a single point of failure, disrupting nearly every container on my network. Observing these cascades in a lab helped me understand which dependencies mattered most and which ones could be made more resilient. The goal was to break things deliberately so that I could design smarter recovery steps.

Another motivation was training under pressure. When something truly fails, it is easy to forget basic troubleshooting. Practicing recovery in a controlled scenario allowed me to test scripts, log analysis, and monitoring tools without fear of permanent damage. Each exercise improved my response time and made my documentation clearer.

There was also an element of curiosity. I wanted to know how my infrastructure would behave under partial failures, such as a slow DNS resolver or intermittent packet loss. Simulating these small degradations often revealed more information than a complete outage would have. They showed how sensitive my services were to even mild instability, which in turn informed how I tuned them for reliability.

How I set up the simulation

Tools and techniques used on Linux hosts

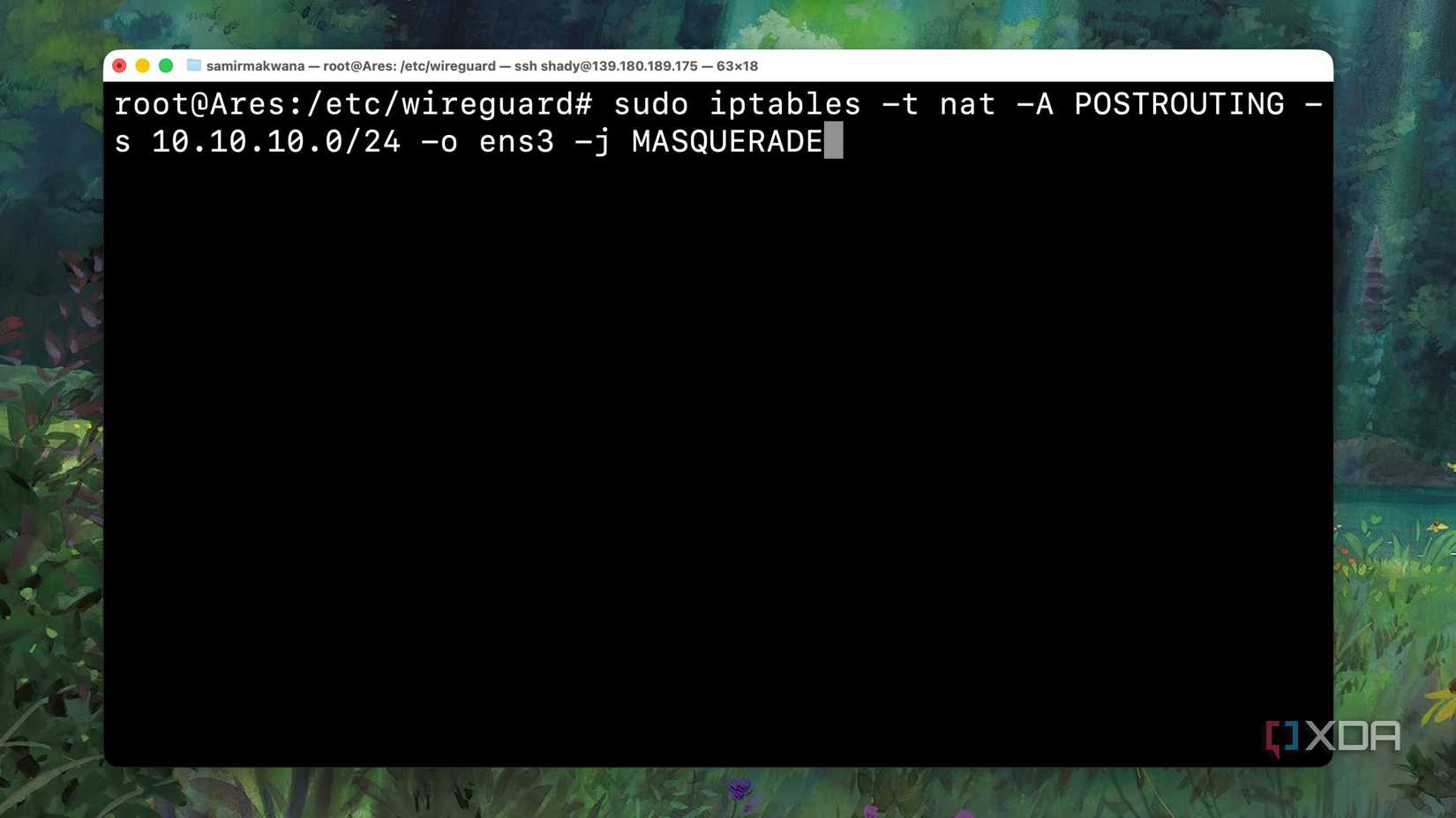

Most of the work was done using basic Linux utilities. I relied on tc to introduce artificial latency and packet loss, while iptables and nftables managed selective blocking of outbound traffic. The combination enabled me to model a range of conditions, from high latency to complete disconnection. Because these tools are already part of the kernel, I could experiment safely without adding new dependencies.

Network namespaces provided isolation between experiments. I used them to create virtual environments that could be broken without affecting the rest of the network. When something went wrong, deleting a namespace restored connectivity immediately. This method also made it possible to run multiple failure scenarios in parallel and observe how different systems reacted.

To test application-level responses, I created lightweight containers that acted as fake upstream services. Some responded slowly, while others refused connections entirely. Using these stubs, I could examine retry behavior, timeout handling, and overall fault tolerance in a realistic way. Every test was logged, and cleanup scripts ensured no settings lingered between sessions.

What went wrong and lessons learned

Surprising failures and practical fixes I found

Even with planning, unexpected issues surfaced quickly. Kernel state sometimes persisted after tests, leaving partial rules behind that blocked legitimate traffic. That residual configuration caused several confusing hours of downtime until I automated the teardown process. Once I implemented a complete cleanup routine, the tests became much more predictable.

Another surprise came from how poorly some services handled temporary failure. Retry storms overloaded upstream systems as soon as connectivity returned, amplifying the very outages I wanted to prevent. I fixed that by tuning retry intervals and adding jitter to backoff algorithms, which spread out the reconnect attempts. This simple change eliminated unnecessary load and smoothed recovery.

Monitoring and alerting also needed serious adjustment. Some alerts never fired, while others flooded me with irrelevant warnings. I rewrote several rules to trigger only after sustained failures and organized them by probable root cause. This helped surface the first real indicator, rather than the last symptom, and reduced the noise during recovery.

Counterpoints and safer alternative approaches

Why real networks and vendors disagree with me

There are valid reasons most administrators avoid running chaotic experiments. Simulating failures in a live network carries a real risk of data loss and user disruption. Vendors often recommend formal chaos engineering frameworks with strict controls, rollback mechanisms, and monitoring safeguards. These systems ensure that each test is deliberate and reversible, which my first attempts were not.

Some professionals argue that lab results cannot fully replicate production behavior. Real networks include unpredictable traffic, hardware quirks, and concurrent workloads that are hard to model. A failure scenario in a lab might look clean but behave entirely differently when thousands of users are involved. I now see the merit in starting with lab simulations, but treating them as training, rather than validation.

For individuals running home labs, the boundary between safe testing and reckless experimentation is thin. The key is containment. Keep destructive testing inside virtualized networks or hosts you fully control. Never direct fault injections toward upstream providers or any shared infrastructure, and document every step so recovery remains possible even if things go sideways.

When to use this approach and when to stop

Situations where outage simulation helps versus harms

Simulating outages is valuable when the goal is to strengthen internal processes. It helps you verify alert accuracy, backup readiness, and recovery automation without depending on a real disaster. For solo home lab users, these controlled experiments can highlight weaknesses early and improve overall system stability. They also provide a sense of confidence that is difficult to gain from passive observation.

There are times, however, when it becomes counterproductive. If your tests begin disrupting unrelated devices, you have crossed a line. I once broke remote backups that relied on my network simply because I forgot they shared the same gateway. Limiting scope and defining clear boundaries prevent those incidents and keep experimentation ethical.

It is also important to consider the needs of other users. If family members or coworkers share your connection, surprise network tests are not fair to them. Schedule downtime windows or perform tests on isolated hardware when possible. Respect for others ensures your learning process does not come at someone else’s expense.

Steps to plan, run, and recover from outages

Define your scope before touching anything. Identify which systems will be affected and confirm that they are under your control.

Automate both setup and teardown. Scripts prevent human error and make each run consistent.

Start with mocks and virtual networks instead of production services.

Configure retries and backoff strategies before testing to avoid storm effects.

Document every test, note what broke, and record the fixes for future reference.

These steps turned my chaotic experiments into repeatable drills. Having a structured plan gave me confidence that I could recover quickly. It also helped me compare results between runs and measure improvement over time.

Commands and utilities I found most useful

The command tc remains the best tool for simulating latency and packet loss. An abbreviation for “traffic control,” tc lets you control delay, jitter, and drop rates with precise timing. Network namespaces isolate failures safely, while iptables or nftables handle selective blocking of ports or destinations. I used dnsmasq for DNS failures and small HTTP containers for mock services. Together, these components covered nearly every failure mode I wanted to study.

These tools aren’t the only ones available for such simulations, and I won’t even argue they’re the best ones. They are, however, robust and suit this sort of purpose quite well. Whatever tools you use, the biggest takeaway from this experiment is that comprehensive documentation is your best friend for network disaster recovery.

I also tracked key metrics during tests to measure effectiveness. Alert response times, recovery durations, retry counts, and false positive rates revealed where my automation needed improvement. Monitoring these metrics transformed each test from a random experiment into a measurable improvement exercise. Over time, I saw evident progress in both detection speed and recovery reliability.

What I ultimately learned from breaking my network

Simulating outages in my lab gave me a realistic view of how fragile my systems could be. The process exposed hidden dependencies, unreliable retry logic, and weaknesses in my alerting setup. Each controlled failure led to an improvement in how I build and maintain services. While I would not recommend reckless testing, a thoughtful approach can make your network far more resilient than it was before.