Since the earliest days of film photography, we’ve been locked into aspect ratios defined by the film itself, whether that’s 3:2 from the standard 35mm film, 4:5 from the 4×5 large format film, or even 1:1 from the 6×6 medium format film that carved out its own niche result. The strange thing is, even after transitioning into digital, the aspect ratio has remained one of the least challenged conventions in photography. Digital cameras became faster, more powerful, and more efficient. But the frame is still the same old 4:3 or 3:2 rectangle that we have been stuck with for over a century.

If you think about it, most of the improvements in digital cameras since the 2010s have revolved around speed. Faster autofocus. Faster burst rates. Faster processing. And don’t get me wrong, these are huge leaps in performance that utilize the better part of technological improvements to produce a much more efficient camera. But here is the honest truth: personally, I think any camera from ten years ago is already fast enough to get the shot. You can shoot portraits, landscapes, even sports, and still get incredible results. After a while, this “faster, better, stronger” narrative in every new camera iteration starts to feel repetitive—a race to achieve more with diminishing returns.

The question is how much faster the camera needs to be practically if it’s not going to change the inherent way that we produce images. That got me thinking. Where is the next big shift going to come from? What could genuinely change the way we approach photography? Then it hit me—square sensors!

We are already starting to see glimpses of it in imaging devices. DJI’s Osmo Action 360 brought it into the conversation, and most recently, Apple slipped it into the iPhone 17’s front-facing camera. At first glance, it might seem like a gimmick. But if you really think about what a square sensor in larger-format digital cameras could unlock, it starts to feel like the next logical evolution.

A Lesson From the Past: APS Film

Back in the 1990s, the APS film system shook things up, though it didn’t live long enough before the transition into the digital era quickly overshadowed it. The APS film allowed photographers to select different aspect ratios—Classic (C, 3:2), High-Definition (H, 16:9), and Panorama (P, 3:1)—on the same roll of film. Back then, it was a game-changer since, for the first time, aspect ratio was not dictated by the format of your negative—it was a creative option on location itself. That was revolutionary for its time, and it opened up new ways of framing without forcing photographers into a single aspect ratio.

In many ways, a square sensor feels like a logical digital descendant of that same disruptive spirit. Just as APS gave us some aspect ratio freedom in the film era, a square sensor could give us fluidity in the digital era, where images live across multiple platforms and aspect ratios matter more than ever.

Why a Square Sensor Might Be a Genius Move

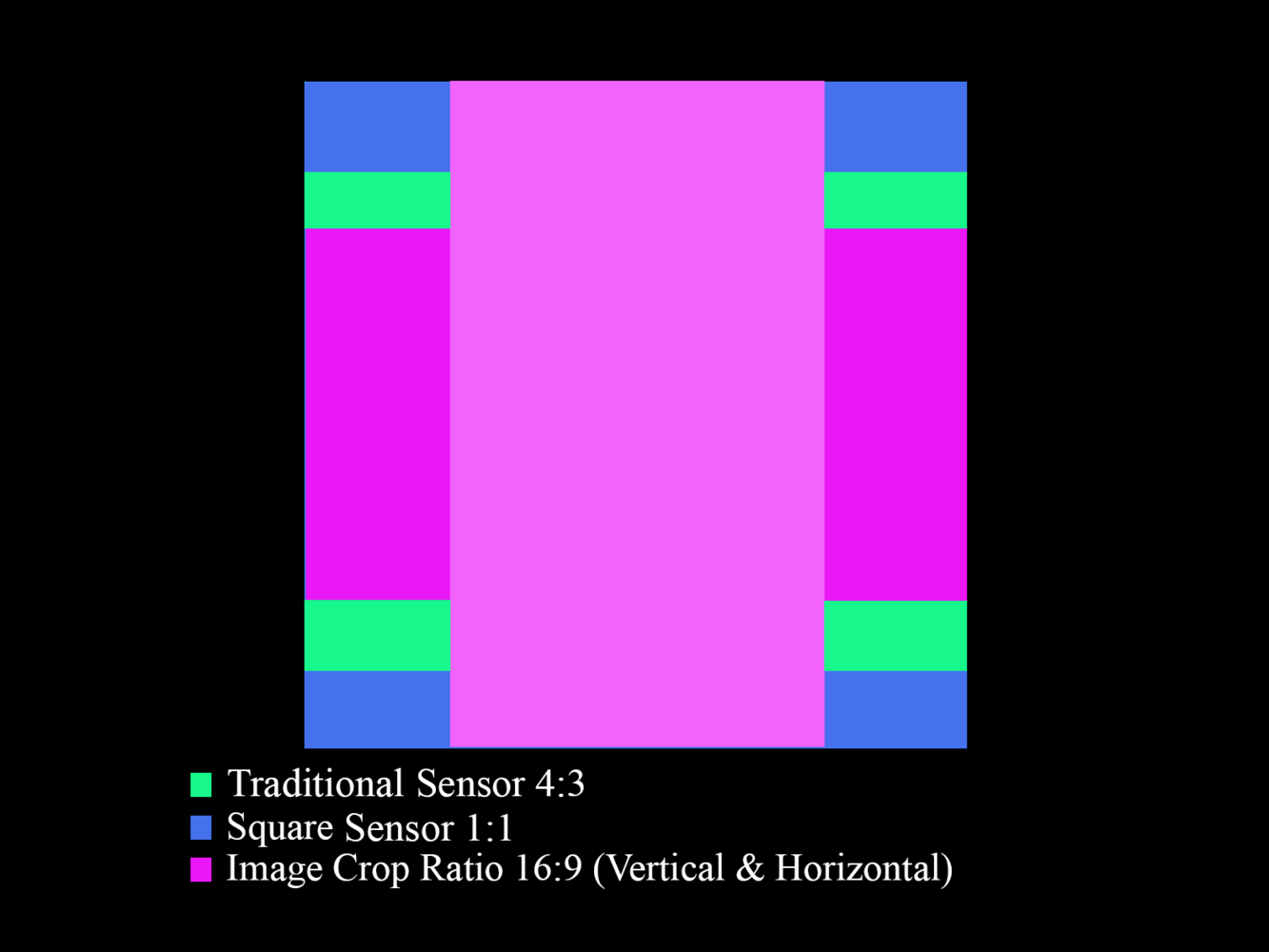

Love it or not, we now live in a multi-platform digital world where we need to adapt to showcase our work. Shoot something for Instagram? It needs 1:1 or 4:5. For YouTube? 16:9. For traditional prints? 3:2 or 4:3. Instead of throwing away part of your frame by cropping into a rectangular image, a square sensor producing a larger square image makes it possible to pull any aspect ratio you want directly from the native capture.

We have already seen this exact idea disrupt the world of consumer video. “Open Gate” recording was first popularized on the Panasonic GH7 and now appears in newer mirrorless cameras like Canon C50 and Panasonic S1R II, which capture the entire sensor readout, not just a cropped slice of it. Videographers love it because it gives them more flexibility in post: they can punch out a 16:9 frame for YouTube or a vertical crop for TikTok and Instagram Reels in the same video that is not so tight in one recording format. It’s one of the biggest shifts in how modern cameras are designed for multi-platform content. Imagine bringing that same freedom into still photography through a square sensor.

Like me, there will always be purists who are firmly against cropping in post, as it often throws the original composition off. This is because you are essentially reframing an image you didn’t plan for at the moment. But this is different. With square sensors, it is not about figuring it out in post—it is about expanding the envelope of what a traditional camera can do. You are still composing intentionally on location, with the advantage of an EVF that previews the crop in real time and not salvaging an image in post. That means you’re not second-guessing yourself later on a computer screen—you’re making the creative decision right in the field, with the help of more sensor real estate. To me, that feels like a natural evolution of composition, not a compromise.

And here’s why the timing makes sense: we have now hit a sweet spot where high-megapixel sensors and power efficiency live in balance. If you recall, almost a decade ago, a 42 MP sensor would chew through batteries—think Sony a7R II. Now, we have 60 and even 100 MP sensors that can run for at least half a day of shooting when paired with processors that are efficient enough not to drain the camera’s battery.

Also, with today’s insane megapixel counts packed into a sensor, why are we still wasting them by cropping in further? A square sensor ensures every pixel is working for you, whether vertically or horizontally. Pair that with efficient modern processors and improved battery technology, and suddenly, what once seemed impractical is actually a sustainable solution that makes a square sensor practical today. Also, think about the possibility of getting better digital IS in video format since we will now have more headroom in the square sensor for stabilization without heavily cropping the image.

Besides, most lenses today project a circular image circle. A traditional full frame or medium format sensor usually throws away the top and bottom part of the entire image circle. That means a square sensor naturally captures more of the lens image circle compared to the standard rectangular crop—essentially, using the lens’s sharpest and cleanest area to its fullest potential rather than trimming away potentially valuable pixels. We have already seen this concept implemented with Fujifilm GFX100R, which has a crop dial baked right into the camera design. Imagine that same concept, but starting from a true square sensor for a much more efficient result.

Besides, most lenses today project a circular image circle. A traditional full frame or medium format sensor usually throws away the top and bottom part of the entire image circle. That means a square sensor naturally captures more of the lens image circle compared to the standard rectangular crop—essentially, using the lens’s sharpest and cleanest area to its fullest potential rather than trimming away potentially valuable pixels. We have already seen this concept implemented with Fujifilm GFX100R, which has a crop dial baked right into the camera design. Imagine that same concept, but starting from a true square sensor for a much more efficient result.

Here’s where it really excites me even more. If you have ever tried holding a camera vertically without a grip, you know how awkward it feels. Twisted wrists, raised elbows that potentially knock someone in the face, and bulky accessories. With a square sensor, suddenly you do not need to rotate the camera anymore. You can compose a vertical crop right there in the EVF without moving an inch. That means less fatigue, less gear, and more freedom to focus on composition.

On top of that, I think implementation of a square sensor will reintroduce something digital has long lost. Film photographers who have shot 6×6 film might agree with me on this, as it produces a refreshing perspective compared to a traditional format. By reintroducing square into the digital mainstream, larger-format cameras could inspire a whole new wave of creative approaches.

Final Thoughts

So here’s my bet: the square sensor is going to be the next big frontier for digital cameras. It practically solves modern needs for flexibility, makes better use of today’s megapixel monsters, and challenges photographers to rethink composition itself. It’s not just about speed anymore—it’s about unlocking better creative freedom with the same camera. I do think that the technology is mature enough to start experimenting with. And honestly, the narrative around faster cameras is getting boring. Maybe it’s finally time for the frame itself to evolve.