The curator and creator of this riveting show is Robin Muir, sometime Vogue contributing editor, archivist for Condé Nast and inspired chronicler of past (and nurturer of future) icons of style and elegance. As Muir is, in another life, a renowned rider to hounds — indeed, a much-admired Master of Foxhounds, supremely glamorous in his mud-spattered white britches — he has equally enthusiastically followed the scented trail, chased and hunted down every facet of this exhibition’s subject.

He has mounted earlier, smaller shows, but Cecil Beaton’s Fashionable World is Muir’s masterpiece.

In the past, Beaton’s work has been treated as somewhat time-locked and ephemeral. Muir sees him as far more important, and presents us with a scholarly and informative overview of Beaton’s golden period, from 1922 to 1955.

It covers the years after Beaton’s emergence from willowy, self-promoting camp-follower of his newly acquired aristo friends, such as Stephen Tennant, into the most inventive, persuasive and disarming arriviste in London, Paris, New York and Hollywood.

Thanks to the designers in each of thosecities, there was a sudden unbounded interest in clothes. Women changed three or four times a day, make-up and hair-colouring became acceptable, and society rather than theatrical beauties were the epitome of glamour, which Beaton was in the vanguard to recognise and record. At the National Portrait Gallery we can see five decades of the photographs that are the essence of his eye for style, and indeed substance.

Every portrait shows Beaton’s astonishing eye, not only for his sitter’s looks but also for an idiosyncratic detail that raises the temperature above mere image. His camera practically speaks, a quality it retained right to the end of his working life, and alternates between an impish, almost amateur joy and a more thoughtful, studied romanticism. Even in close-up these portraits never have the invasive intensity most of the following wave of photographers went in for, but tell us the best about his subjects.

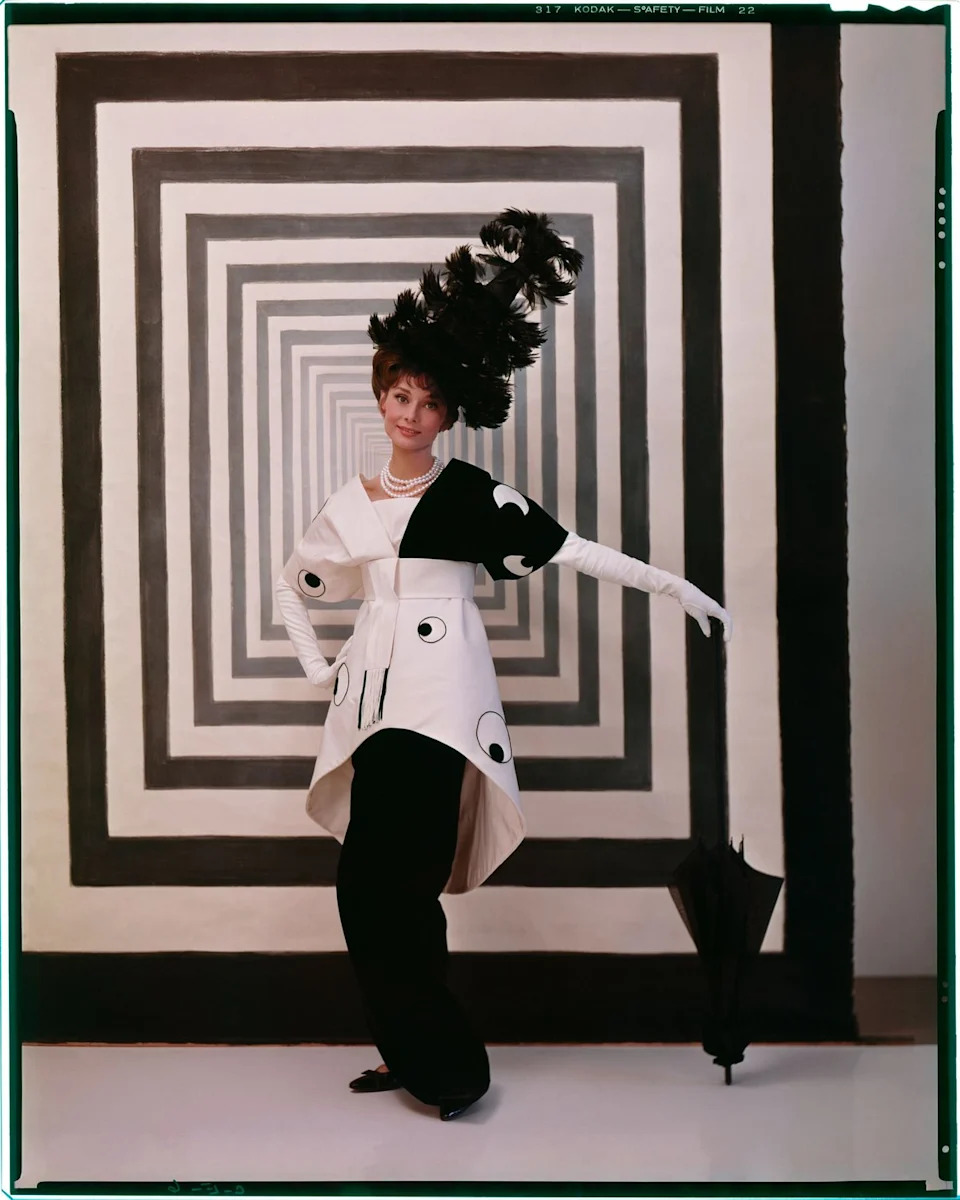

Audrey Hepburn in costume for My Fair Lady (The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive,)

Hollywood muses

Sometimes he admits to more. Of Fred Astaire, shown neat as a pin in a checked suit rather than the usual top-hat-and-tails, he writes, puppy-like, “I should adore to … sleep with him, just to stroke him all over, and then go to sleep.” Nearby is a delicious, almost caricature-like sketch of Astaire’s enchanting sister Adele, who was rumoured to have initiated Beaton into the pleasures of straight sex, though others maintain it was Doris Castlerosse, portrayed a few frames along, of whom Winston Churchill legendarily said “Doris, you could make a corpse come”.

One wishes the show had a soundtrack of Beaton commenting on his sitters, about whom he gave vivid, telling, details. He described his great friend Mona — Mrs Harrison Williams — as having a complexion of “pink, and wet, marble” and on meeting Audrey Hepburn noticed “her child-like head, as compact as a coconut, with its cropped hair and wispy, monkey-fur, fringe”. Even his on-off inamorata, Greta (which he always pronounced Grayta) Garbo, of whom there are strangely few images on view, has a “knife-like mouth with lips permanently moistened by her adder-like tongue”. He could be cutting too. During a sitting for Coco, Katharine Hepburn heard Cecil say he needed some shaving foam. She barked: “Why can’t you men just use soap and water like my father?” Beaton purred “Maybe that’s why you have such rough skin, Kate dear.”

Bravery and dash

On one of the most arresting of the Gallery’s walls is the exact reverse of these symphonies in silver, or that race of gilded gods and goddesses. Beaton’s work documenting the hell and hardship for troops during the Second World War is profoundly moving, especially when one thinks of the bravery and courage it took to fly, often all night, to far-Eastern zones of warfare, in juddering, metal-floored propeller planes. But he had innate bravery; staying at my Arizona ranch Cecil would leap blithely onto a sprightly Arabian and gallop away into the desert, whereas he-man Horst, another (and rival) photographer staying at the same time, just leant on the corral fences, swirling a triple-strength martini.

Naturally the greatest interest to many will be the room devoted to what Beaton is now most famous for; the photographs of his costumes in the Black Ascot sequence in My Fair Lady, here presented as a final, colourful panorama people will love. Personally I am not that keen on them. Even on Hepburn, the clothes seem oddly lumpen and stiff in these stills, whereas in movement on stage and film they become magical. But all was not sweetness and light between designer and the movie’s famed director and star. In Hollywood, the summer of 1963, Beaton took me on the set of My Fair Lady. Driving back from Burbank he let fly, “Oh, that ghastly George Cukor. His vulgarity is ruining the film … and that absolute beast Rex Harrison, with his false teeth.”

I was fortunate enough to know many of those immortalised so triumphantly by Beaton, and visitors can now appreciate them in this show, mounted equally triumphantly by Muir. It is, in Cecil’s favourite adjective, exhilarating. Like a good day’s hunting.

Cecil Beaton’s Fashion World is at the National Portrait Gallery until January 11, npg.org.uk

Nicky Haslam; Britain’s ultimate interior designer, also known as an artist, author of seven books, cabaret singer, book reviewer, art editor, memoirist and literary editor. www.nickyhaslamstudio.com