In many respects, 270 Park, the new 60-story office tower for JPMorgan Chase (JPMC), in Midtown Manhattan, is exactly the type of building one would expect the architects at Foster + Partners—masters of precisely detailed and engineered structures—to design as the global headquarters for the multinational financial-services company. At 1,388 feet (the sixth-tallest in the city), the reportedly $3 billion, 2.46 million-square-foot skyscraper exudes a staid but palpable corporate power—a restrained opulence.

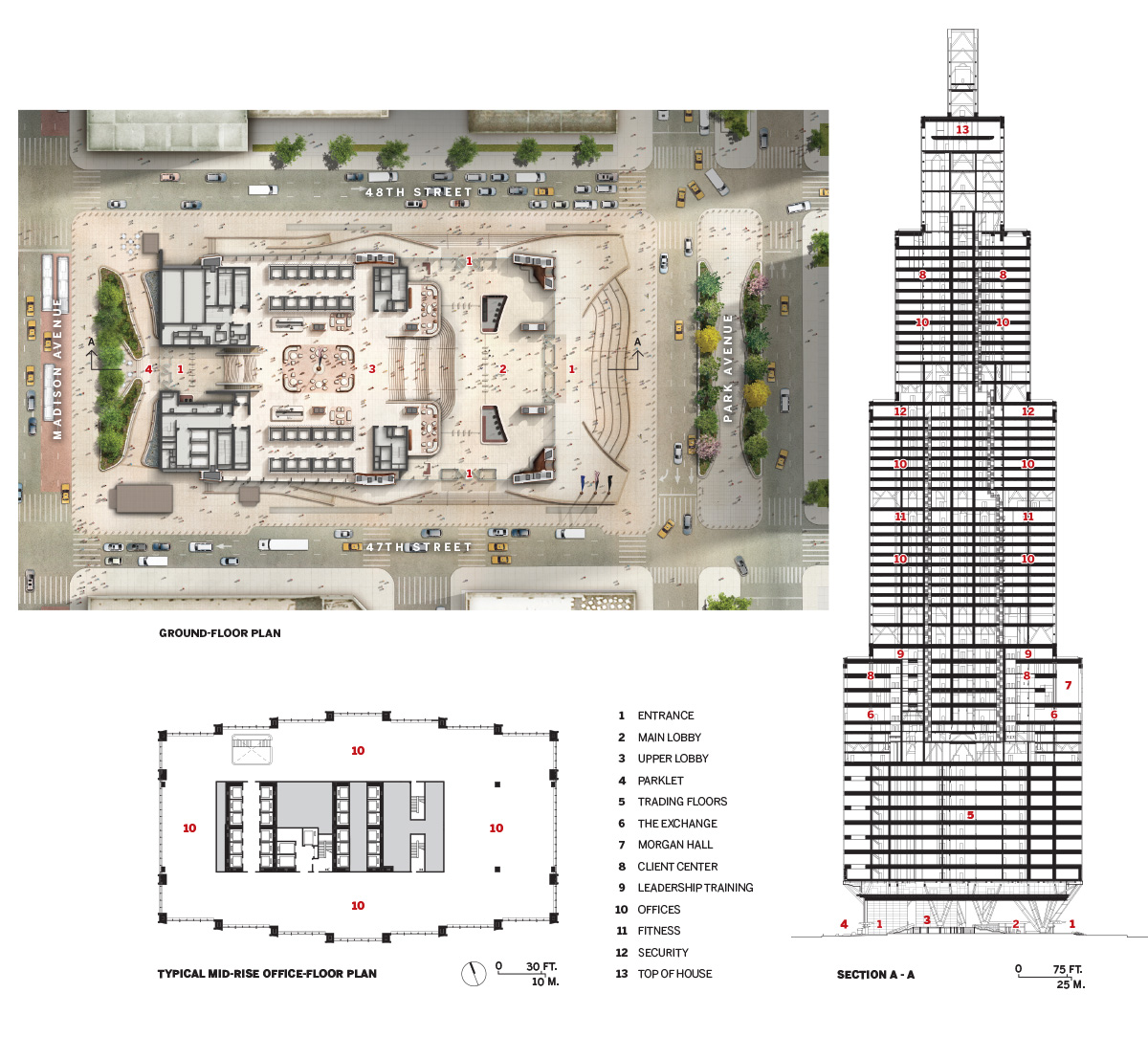

Occupying the full block bounded by Madison and Park avenues and 47th and 48th streets, the glass-and-steel building with diamond-shaped bracing resembles an attenuated high-tech version of classic Art Deco towers on the skyline, especially from the north and south, where its stepped profile, with four sets of symmetrical setbacks, is particularly apparent.

The front elevation at lobby level cants precipitously toward Park Avenue. Photo © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners, click to enlarge.

The tower is more surprising where it meets the ground. Here, fanlike groupings of muscular columns splay from six pivot points surrounding the base, seemingly supporting the weight of the entire tower and producing the somewhat incongruous effect of a football player balanced on toe shoes. This unusual configuration is the product of serious site constraints: the extensive track network belowground for the nearby Grand Central Terminal and Grand Central Madison station severely limited the possible structural bearing points. The perimeter fan-shaped assemblages are some of the most visible elements in a sophisticated structural system, designed by engineers from Foster + Partners and Severud Associates, for transferring the weight of the tower above to the available touch-down spots below.

The tower meets the ground with fan-like groups of muscular columns. Photo © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

Inside, at ground level, more pieces of the complex load-transfer system—four pairs of 50-foot-tall V-shaped columns that march the 360 feet from east to west—set the tone for the heroically scaled lobby, almost entirely open, with a clear view from the Park Avenue entrance, and framed by twin elevator cores to Madison Avenue beyond. The space is minimal yet lavish, with smooth planes of travertine defining the walls and floors, and bronze enclosing the steel structure.

The tower was made possible by a 2017 rezoning and by the purchase of unused air rights from nearby buildings. It replaces JPMC’s previous headquarters at the same address, SOM’s 52-story, 707-foot-tall office tower completed in 1960 for the Union Carbide Corporation. Designed by Gordon Bunshaft and Natalie de Blois, the building was taken down starting in 2019, even though many in the architecture community considered it a prime expression of postwar corporate Modernism (not to mention a rare example of a tall building designed by a woman). Environmentalists objected because of embodied-carbon concerns, advocating instead for its adaptive reuse. At the time, the tower was the tallest in the world to have been voluntarily demolished. But JPMC maintains that the old building was no longer fit for purpose, with low ceiling heights, not enough elevators, and too little space overall. When it decided to replace the tower, the company had more than 6,800 people working in a building designed for 3,500, says David Arena, JPMC’s head of global real estate.

The new 270 Park, which can accommodate as many as 14,000 employees, has been conceived, says Arena, not only for a much greater number of people but also for better “sociability.” Above the lobby and eight trading floors are several levels of shared amenities extending to the first setback at floor 17, such as conference and leadership-training facilities and a dining floor with nearly 20 different eateries. At level 14, one of several contiguous floors where the twin elevator cores transition to a more traditional central one, spaces include Morgan Hall—an expansive triple-height volume that can be used for informal gatherings or for town-hall-style meetings of up to 1,000 people.

Morgan Hall’s furniture can be rearranged so that it accommodates a variety of uses. Photo © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

The offices on the floors above, designed by Gensler, which also designed many of the amenity spaces, are organized around two-story community hubs that resemble living rooms. Arranged primarily as open cubicles, the 10½-foot-tall workplace floors have features intended to enhance productivity and health, including low cubicle partition heights, to take advantage of the daylight penetration possible in the relatively narrow span from the perimeter to the core; circadian electric illumination; and a ventilation system that provides double the amount of outdoor fresh air required by code.

A minimal, open stair connects two amenity floors. Photo © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

The new tower includes a long list of additional sustainability measures helping to put it on track for LEED Platinum designation, including a triple-glazed facade, an “intelligent” building-management system that predicts and adapts to energy needs, and an advanced water-storage and -reuse system. The slab-and-metal-deck floor assembly uses ground-glass pozzolan (made from recycled glass) to replace about 40 percent of the carbon-intensive Portland cement of a typical concrete mix.

JPMC says that its all-electric tower will be operationally net zero because it is purchasing carbon-free power from hydroelectric plants upstate. Renewable energy experts say that purchasing off-site green power is a valid net zero strategy, but, to qualify, JPMC’s purchased energy should be the result of a long-term contract with the provider. It should also represent “additionality,” or new generation capacity built as a result of that commitment. So far, JPMC has not provided details showing that its hydropower deal meets either criterion.

The project also claims a 97-percent rate for diversion of the demolition waste of the Union Carbide tower from landfills. Among the many recovered materials was structural steel that was sold to a recycling company, for processing into new steel components, and finishes like acoustic ceiling tiles and carpet tiles that were converted into new ceiling and carpet products. Though keeping so much waste out of landfills is laudable, JPMC’s accounting does not consider the energy required for the recovery and recycling processes. A more environmentally sound strategy would have been to reuse rather than recycle the materials, particularly the structural ones. By far the most sustainable option would have been to maintain them in situ as part of a radical adaptation along the lines of KPF’s 2023 overhaul and expansion at One Madison Avenue in New York, or 3XN’s Quay Quarter Tower, which doubled the floor space of a 1970s Sydney tower.

From its expression on the skyline to its expansive gathering spaces and daylight-filled offices, 270 Park has a lot to admire. And it most certainly epitomizes a workplace of the future. That it comes at the expense of losing a significant 20th-century office building is, however, lamentable.

Image courtesy Foster + Partners

Credits

Architect:

Foster + Partners

Architect of Record:

Adamson Associates Architects

Interior Architects:

Gensler (office floors, client center, leadership training, fitness center, health & wellness spaces); SOM (trading floors); Studios (dining floor)

Consultants:

Foster + Partners, Severud Associates (structure); JB&B (m/e/p); Philip Habib + Associates (civil); Mueser Rutledge Consulting Engineers (geotechnical); Vishaan Chakrabarti (design collaborator); Heintges (facades); Ken Smith Workshop (landscape)

General Contractor: AECOM Tishman

Client:

JPMC

Size:

2.46 million square feet

Cost:

Withheld

Completion Date:

October 2025

Sources

Glazing:

AGC Interpane, Glassbel, Pilkington, FinnGlass

Insulated Panels:

Kingspan

Metal Panels:

POHL Facades

Pavers:

Wausau