Voters in Ireland will head to the polls on Friday to elect a new president for a seven-year term.

While the Irish presidency is a mostly ceremonial role, this election takes place amid a historic shift towards a more polarised political system, Barry Colfer, director of research at Dublin’s Institute of International and European Affairs, told Al Jazeera.

Since the establishment of the Irish Free State in December 1922 and the subsequent end of the Irish Civil War in May 1923, Irish politics, unlike in other European countries, have not been drawn along left-right lines, he said. “What we’re seeing today for the first time in Irish history is a presidential election between objectively left-wing and right-wing candidates.”

This change has become more apparent in recent years. In the 2020 general election, left-wing nationalist party Sinn Fein – the former political wing of the Irish Republican Army – won the most first-preference votes for the first time since the country’s founding, bringing an end to the traditional two-party dominance of the centre-right parties Fianna Fail (FF) and Fine Gael (FG). By the end of the voting process, Sinn Fein had 37 seats, finishing close to neck-and-neck with FF at 38 and FG at 35.

There are 174 seats in Dail Eireann (Irish for Ireland’s lower house of parliament) in total, with 88 needed to form a government.

The two previously dominant parties’ origins date back to the Irish Civil War and its aftermath, with FG’s forerunner supporting the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which granted the country partial independence, and FF opposing it.

For the first time in their history, FF and FG were forced to enter into a formal coalition government with the Green Party in 2020 to be able to form a government. Following the 2024 election, they partnered with independents instead of the Greens.

President Michael D Higgins at the Irish National Ploughing Championships in Screggan, Ireland, September 16, 2025 [Clodagh Kilcoyne/Reuters]Who serves as president of Ireland, and what do they do?

President Michael D Higgins at the Irish National Ploughing Championships in Screggan, Ireland, September 16, 2025 [Clodagh Kilcoyne/Reuters]Who serves as president of Ireland, and what do they do?

The presidency has a relatively limited political role, comparable to that of monarchs in other countries, said Gail McElroy, a professor of political science at Trinity College Dublin. It is “seen as a unifying role beyond politics”.

The president represents Ireland abroad and hosts visiting heads of state and other dignitaries at the official presidential residence, Aras an Uachtarain, in Dublin’s Phoenix Park.

The president is, above all, responsible for ensuring that the Irish Constitution is followed.

After the presidency was established in 1938, one year after the current Bunreacht na hEireann (Irish constitution) was adopted, it was generally held by a statesman with a long affiliation to one of the two main political parties. For instance, Eamon de Valera, one of the leading political figures during Ireland’s War for Independence and founder of FF, served as taoiseach (prime minister) from 1937 to 1948, 1951 to 1954 and from 1957 to 1959, and then as the country’s third president from 1959 to 1973.

The election of Mary Robinson, Ireland’s first female president, in 1990 “marked a watershed moment”, McElroy told Al Jazeera.

The election of Robinson, who had been nominated by the Labour Party and the Workers’ Party, and also received official support from the Green Party, transformed the presidency from a largely symbolic, conservative office into one with more significant diplomatic influence. Her presidential campaign had included a commitment to expand the role of the president into a more active one focused on social issues and to foster an image of a “new Ireland”.

Before becoming president, she had served as a senator in Seanad Eireann (Irish senate) from 1969 to 1989, and been a member of the Dublin City Council from 1979 to 1983.

During her time in office, she signed two significant bills that she had fought for throughout her political career: a 1992 bill to fully liberalise the law on the availability of contraceptives, and a 1993 bill fully decriminalising homosexuality. She also signed the legalisation of divorce into law in 1996.

As president, Robinson also took significant steps to foster an atmosphere of reconciliation between Ireland and the United Kingdom. She made history by being the first Irish president to meet a British monarch, then Queen Elizabeth II, in an official capacity. She also controversially met and shook hands with Gerry Adams, then the leader of Sinn Fein, a significant move towards dialogue at a critical time in the Northern Ireland peace process.

And finally, Robinson used her presidential platform to advocate for human rights worldwide, notably becoming the first head of state to visit Somalia in 1992 following the civil war and famine, drawing international attention to the country’s humanitarian crisis.

Mary McAleese, the first person born in Northern Ireland to serve as president, held the office from 1997 to 2011 – like Robinson, during pivotal years for the Northern Ireland peace process that culminated in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement ending the three-decade conflict that had begun in the late 1960s in Northern Ireland, known as The Troubles. Her emphasis on reconciliation culminated in a historic state visit to Ireland by Queen Elizabeth II.

Michael D Higgins, president since 2011, has stretched the conventions of his office with, at times, strong criticism of government policy on both domestic and foreign policy issues, particularly regarding the country’s housing crisis and longstanding policy of military neutrality.

Higgins has also been a vocal supporter of the Palestinian cause, in line with the overwhelming majority of the Irish public, and has been unequivocal in calling for a permanent ceasefire since the start of Israel’s war on Gaza.

The Irish government has been one of the most critical voices of Israel within the European Union, supporting South Africa’s genocide case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague.

Higgins has described Israel’s war on Gaza as the “incredible destruction of an entire people” and echoed the Irish government in calling it a breach of international law.

At times, Higgins has made statements and proposed actions that go beyond the realm of formal government policy. He said accusations of anti-Semitism against those who criticise the policies of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu amount to “slander against Ireland”, and has even suggested that Israel and the countries that supply it with weapons should be excluded from the United Nations.

People take part in a protest organised by the Ireland Palestine Solidarity Campaign, outside the Central Bank of Ireland in Dublin on May 27, 2025 [Niall Carson/PA Images via Getty Images]Who can stand for the presidency and who can vote?

People take part in a protest organised by the Ireland Palestine Solidarity Campaign, outside the Central Bank of Ireland in Dublin on May 27, 2025 [Niall Carson/PA Images via Getty Images]Who can stand for the presidency and who can vote?

Any Irish citizen aged 35 or above can seek nomination for the presidency by following one of three routes.

One way to be nominated is through being endorsed by 20 members of the Oireachtas (parliament). There are 174 members of the Dail and another 60 senators in the Seanad. Alternatively, a presidential hopeful can be nominated by four out of Ireland’s 31 local authorities.

A sitting president may also nominate themselves to run for a second and final term, without the support of members of the Oireachtas or local authorities. In recent history, both McAleese and Higgins nominated themselves for second terms.

Only Irish citizens who are at least 18 years old can vote for the president. About 3.5 million people in the country are eligible. Official voter turnout is generally low for presidential elections in Ireland, with the last one in 2018 at just 43.9 percent.

Who is standing in the upcoming election?

Officially, there are three presidential candidates: Catherine Connolly, Heather Humphreys and Jim Gavin, who withdrew from the presidential race earlier this month – but after a deadline for doing so had passed, meaning that votes for him can still be counted.

Whichever candidate is elected will have large shoes to fill, as Higgins, whose second term ends in November, is regarded as one of Ireland’s most popular politicians.

While pollsters currently have Connolly as the favourite for the race, more than 35 percent of respondents have indicated in polls that they will either spoil their vote or not vote at all.

Catherine Connolly

Connolly, 68, an independent, is backed by a coalition of left-wing parties, including Sinn Fein, the Green Party and the Social Democrats, among others, and several independent Oireachtas members.

Connolly began her political career in 1999, when she was elected to the Galway City Council as a Labour candidate and then served as mayor of Galway, in the western part of the country, from 2004 to 2005. She left the Labour Party in 2007 due to a dispute over candidate selection for the general election, leading her to run as an independent candidate.

She has been serving as the TD (Teachta Dala; member of the Dail) for Galway West since 2016. Connolly has also worked as a barrister and clinical psychologist.

Connolly would be expected to continue Higgins’s legacy of criticising the government, “and maybe go even further than Higgins”, given that she has always been in opposition, both when she was a member of the Labour Party and as an independent, said Colfer.

Connolly has said she is running to use the presidency as an active moral and ethical voice for the nation, with a strong focus on addressing the housing and homelessness crisis and supporting the most vulnerable, including people with disabilities. Her platform also includes promoting the Irish language and supporting a vision for a united – and more equal – Ireland. And lastly, she is campaigning on defending Irish neutrality as an active tradition of peace-making and advocates for human rights on the international stage, including strong support for the Palestinian people.

Regarding Israel’s war on Gaza, she has said: “Israel have committed genocide in Gaza. The normalisation of genocide is catastrophic for the Palestinian people, and it is catastrophic for humanity. History didn’t begin on October 7. I will stand in solidarity with the Palestinian people as long as I have breath in my body.”

Opinion polls conducted during the presidential campaign indicate that young people overwhelmingly support Connolly, along with those aligned with the left-wing and independent political parties backing her presidential bid.

Connolly is the favourite to win the presidency, with the latest poll conducted by Irish broadcaster RTE putting her support at 38 percent.

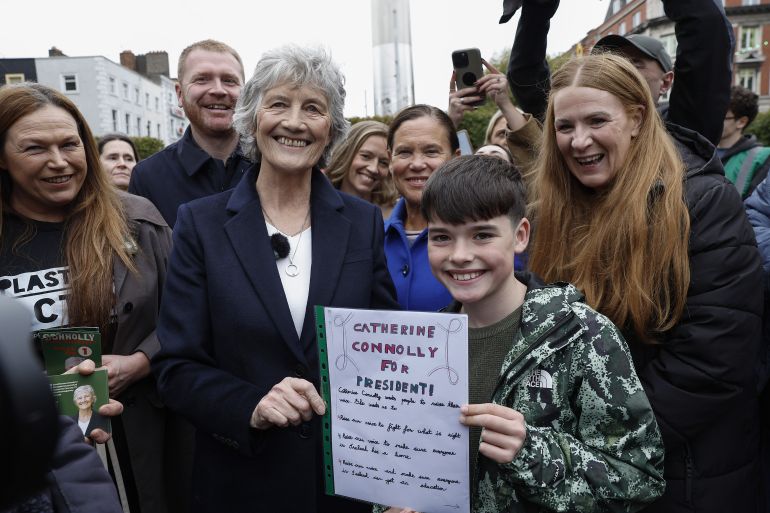

Independent candidate Catherine Connolly meets a young supporter, Joshua, 10, on the campaign trail in O’Connell Street, Dublin, on October 5, 2025 [Conor O’Mearain/PA Images via Getty Images]Heather Humphreys

Independent candidate Catherine Connolly meets a young supporter, Joshua, 10, on the campaign trail in O’Connell Street, Dublin, on October 5, 2025 [Conor O’Mearain/PA Images via Getty Images]Heather Humphreys

Humphreys, 62, the candidate for FG, is an experienced cabinet member, having held a range of portfolios, including justice and rural development, from 2014 to early 2025.

She also served as a TD for the Cavan-Monaghan constituency, on the border with Northern Ireland, and as the FG’s deputy leader.

Given Humphreys’s political background, she would be much more likely not to challenge government orthodoxy, thus returning the office to a more ceremonial one, said Colfer.

Her campaign is centred on celebrating local volunteerism and extending the presidency’s reach across the country. A key aspect of her campaign is also her background as a Presbyterian from Monaghan. She has pledged to use this identity to build bridges between nationalist and unionist communities in Northern Ireland and promote reconciliation across the island, framing herself as a unifying candidate. Humphreys has also strongly advocated for the development and renewal of rural Ireland and support for Irish businesses internationally. Lastly, she has pledged to support the most vulnerable, such as promising increased pension/disability payments.

Humphreys is predicted to win 20 percent of the vote.

FG’s Heather Humphreys is greeted by supporter Tim McCarthy during campaigning for the Irish presidential election in Co Cork, on October 22, 2025 [Noel Sweeney/PA Images via Getty Images]Jim Gavin

FG’s Heather Humphreys is greeted by supporter Tim McCarthy during campaigning for the Irish presidential election in Co Cork, on October 22, 2025 [Noel Sweeney/PA Images via Getty Images]Jim Gavin

Gavin, 54, was the candidate for FF, which is the largest party in parliament and is led by the prime minister, Micheal Martin. He is a former Gaelic football team manager who also served for 20 years in the Irish defence forces. Gavin is currently working as the chief operations officer for the Irish Aviation Authority.

Gavin announced his withdrawal from the race on October 5 following allegations in the Irish Independent newspaper that he owed 3,300 euros ($3,850) to a former tenant. His name still appears on the ballot, however, as he withdrew after the deadline for doing so had passed. “This means he is still a valid candidate,” according to the Irish Examiner newspaper. “Any votes cast for him will be counted as normal, meaning he could still win and become Ireland’s 10th president.”

Ever since Gavin withdrew his bid, he has no longer appeared in presidential debates held on Irish media outlets, narrowing the presidential contest to a two-horse race.

Gavin is currently predicted to secure just 5 percent of the vote.

If Gavin won the election, “he would presumably decline the role and therefore trigger a fresh election”, which would need to take place within 60 days, according to Irish online newspaper The Journal.

FF candidate Jim Gavin leaving the first presidential debate on The Tonight Show, at Virgin Media Television Studios in Dublin on September 29, 2025, before he announced his withdrawal from the race [Niall Carson/PA Images via Getty Images]How does voting work?

FF candidate Jim Gavin leaving the first presidential debate on The Tonight Show, at Virgin Media Television Studios in Dublin on September 29, 2025, before he announced his withdrawal from the race [Niall Carson/PA Images via Getty Images]How does voting work?

Ireland uses an electoral system of proportional representation known as the Single Transferable Vote.

In this system, a voter ranks candidates in order of preference by marking the numbers 1, 2, 3 (in the case of this presidential election) on their ballot. The voter is free to vote for just one or all three of the candidates.

Before the official counting can take place, ballots are sorted in order of first-preference votes. Any spoiled votes are placed to one side, as they will not be counted.

If no one secures an absolute majority of first-preference votes, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated and their votes are transferred to the next preference marked by each voter.

This elimination and transfer process continues until one candidate secures more than 50 percent of the votes.

As Gavin’s name remains on the ballot, “it is possible that his transfers could yet be very important in deciding who will be the next president of Ireland”, according to the Irish Times newspaper.

The election will take place on October 24, with the result expected the following day. The new president will be inaugurated at a ceremony in Dublin Castle.

What are the key issues in this election?

A number of political issues have emerged during the most recent presidential debates as both the leading candidates have parliamentary track records on issues important to voters, said Colfer.

Housing crisis

At the 2020 and 2024 general elections, housing was a defining electoral issue for voters. The country’s housing crisis peaked in 2013, as a severe supply shortage combined with a growing population resulted in a rapid escalation in rent and house prices, leading to record levels of homelessness and emigration, as well as widespread unaffordability.

Higgins has reflected public anger with the government over this issue, condemning the housing crisis as “our great, great, great failure”, saying that it could no longer be considered a crisis but “a disaster”.

It has been difficult for Humphreys to appease voters when responding to questions on this topic, given that she has been serving in government during this time, said Colfer.

Triple lock mechanism and Irish neutrality

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Ireland has been reckoning with its policy of military neutrality, which was adopted at the outbreak of World War II, dubbed “The Emergency”, and has since been maintained by successive governments.

While this policy, as well as a legislative mechanism known as the triple lock, are not “necessarily related”, some say that reforming the mechanism, as the Irish government has committed to do, “risks undermining the policy [of neutrality] and is a slippery slope towards abandoning it”, said Colfer.

While opinion polls have repeatedly indicated that the majority of Irish people want to maintain the country’s policy of military neutrality, the discourse around other aspects traditionally associated with the policy, including defence spending and the triple lock, is “more refined now”, he said.

“There is an understanding now that both more defence spending and replacing the triple lock doesn’t necessarily compromise or undermine neutrality.”

An Irish Times poll conducted earlier this year found that 63 percent of voters support the country’s current model of neutrality, while 47 percent support maintaining the triple lock.

A separate Irish Times poll conducted in June 2023 found that 55 percent of voters supported “significantly increasing Ireland’s military capacity” to defend its airspace and territorial waters.

Under the triple lock, no more than 12 military personnel can be deployed to participate in overseas peacekeeping operations without the approval of all three of the Irish government, the Dail and the UN.

The Irish government’s main argument for reforming the mechanism is to prevent a permanent member of the UN Security Council, like Russia or China, from having a de facto vote on Ireland’s participation in international peacekeeping missions because of the UN part of the triple lock. No new peacekeeping mandate has been approved by the council since 2014.

Higgins has accused the government of “playing with fire” by holding public discussions that he believes are creating a dangerous “drift” away from Ireland’s policy of military neutrality and that risks “burying” Ireland in other people’s agendas.

He has also criticised increased military spending as “shocking”, warning that it perpetuates “war as a state of mind” at the expense of investing in essential areas such as education and healthcare.

While the Irish government announced in July 2022 the largest increase in defence spending in the country’s history, jumping from 1.1 billion euros ($1.3bn) to 1.5 billion euros ($1.7bn) by 2028, Ireland continues to have one of the lowest defence budgets in Europe.

The government argues that reforming the triple lock would not change the policy of military neutrality, which it defines as “non-membership of military alliances or mutual defence arrangements”.

Over the course of the presidential campaign, Connolly has positioned herself as a strong defender of Ireland’s longstanding policy of military neutrality and the triple lock mechanism.

“I believe in neutrality as an active, living tradition of peacemaking, bridge-building, and compassionate diplomacy. The triple lock is core to our neutrality. It is one of Ireland’s greatest strengths, and I will defend it and the triple lock with determination.”

Connolly has also stated that she is opposed to any move that would lead the country to become involved in “dangerous NATO or EU militarisation”.

Humphreys, however, has stressed that while she supports a review of the triple lock, she is not proposing abandoning Ireland’s policy of military neutrality.

Regarding the triple lock, she has said: “No other country should have a veto over where members of the Irish defence forces serve.”

Humphreys has framed herself as a candidate who would maintain strong relationships with European partners and allies and has warned against Connolly’s approach, which she says could be seen as “insulting Ireland’s allies” like Germany, France, the United States and the UK.

Irish reunification

Since Brexit, Britain’s departure from the EU in January 2020, the topic of Irish reunification has been much more in the public realm than it was even 10 years ago, said Colfer.

Both main candidates have stated that they are proud Republicans and express support for Irish reunification.

While Connolly may appear to have the obvious advantage with the official support of Sinn Fein, Colfer argues that Humphreys may actually have the upper hand due to her personal connection to Northern Ireland.

In addition to her religious background and upbringing, Humphreys has a connection to the Orange Order, a conservative Protestant fraternal society associated with British unionism, through her father and husband, who are both former members. Her grandfather signed the Ulster Covenant in 1912, a petition against Irish self-government.

These links to a longstanding Protestant organisation “will help open up a line of communication with Unionists” for Humphreys, seen as important in bridge-building between Northern Ireland’s Catholic and Protestant communities ahead of a reunification referendum, said Colfer.