Savita PatelBBC News, California

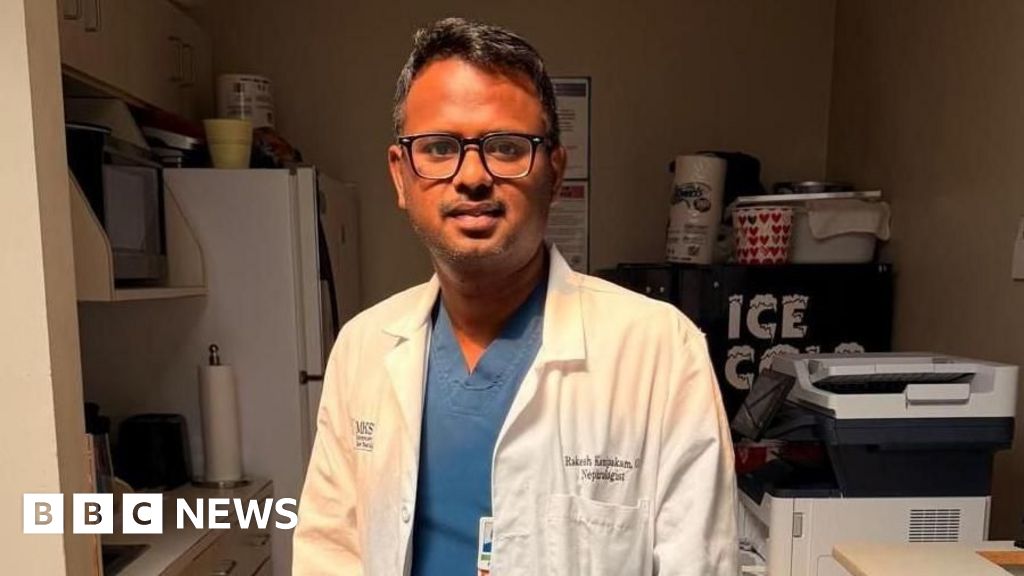

Mahesh Anantha

Mahesh Anantha

Dr Mahesh Anantha’s practice is indispensable in the remote US town he works in

Dr Mahesh Anantha is one of the few interventional cardiologists for miles around Arkansas’s Batesville area, a rural pocket of the US.

Surrounded by farmland and a smattering of small industries and banks, the pastoral town with a population of some 11,000 people serves as a hub for nearby villages and cities, making Dr Anantha’s often lifesaving practice indispensable.

“There is no other medical facility around for an hour or two’s drive, so people rely on us for everything,” he says.

A gold medallist from Madras Medical College in southern India, Dr Anantha is among thousands of immigrant doctors working in small and remote towns in the US.

Some 25% of doctors providing care in the US are foreign-trained. Recent data shows that 64% of them practise in the vast underserved rural areas where American graduates are reluctant to work, filling a crucial gap in the country’s healthcare system. Many of these doctors are on H-1B visas and some even spend their entire careers on them as they wait for a green card, making them vulnerable to unexpected job losses and long-term instability.

So last month’s announcement by Donald Trump’s administration that it will hike skilled-worker H-1B visa fees for new applicants to $100,000 (£74,359) sparked fear and anxiety among the roughly 50,000 India-trained doctors working in the US. In the days after the move, there was little clarity on how it would affect medical professionals, fuelling uncertainty about their futures, even for those who have spent years building careers and communities in the US.

As outrage spread, a White House spokesperson told Bloomberg via email on 22 September that “the proclamation allows for potential exemptions, which can include physicians and medical residents”. On Monday, US officials announced that the fee “does not apply to any previously issued and currently valid H-1B visas”.

While this clarification may give some relief to doctors who are already working on H1-B visas in the US, there are still questions around whether the steady supply of Indian medical professionals to the US would continue in the future.

The earlier executive order on the visa hike says that the higher fees can be waived if the secretary of Homeland Security establishes that appointing certain workers is “in the national interest”. But the medical industry and groups point out there is no indication that any category of workers, including those in the medical field, has been exempted from this fee.

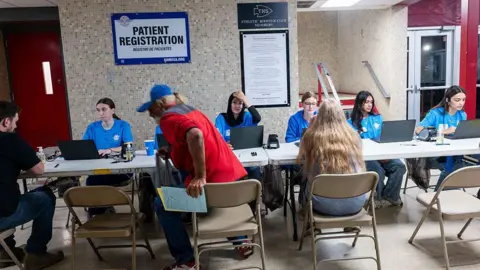

Getty Images

Getty Images

Experts worry the H-1B visa fee hike could make it harder for rural hospitals to bring in new clinicians from abroad

Many worry that higher costs for hospitals to hire doctors and other workers could ripple through the system. Last month, more than 50 groups led by the American Medical Association (AMA) wrote to Kristi Noem, the secretary of Homeland Security, emphasising that the fee hike could discourage hospitals from hiring H-1B doctors, affecting future supply pipelines and limiting patients’ access to care in communities that need it the most.

“We have heard from health systems who say this fee would be devastating,” says Dr Bobby Mukkamala, president of the AMA. The son of Indian immigrant doctors, Dr Mukkamala is the first Indian-origin doctor to head the AMA.

According to research, one in five immigrant doctors in the US is of Indian origin.

Supporters of the hike argue that tighter immigration policies are necessary to keep American jobs for Americans.

But research from the University of California San Diego’s (UCSD’s) School of Global Policy and Strategy shows that relaxed visa requirements don’t impact the jobs of US medical graduates. In fact, it enables more foreign-trained doctors to practise in remote and low-income areas.

The AMA also emphasises that “international medical graduates are not taking jobs from US physicians”, but are instead “filling critical gaps in care”.

Like several other western countries, the US has long faced a shortage of doctors and nurses. The UCSD study projects that the country will face a shortfall of 124,000 doctors by 2034.

The impact will be particularly felt in the countryside as most American medical graduates opt for bigger cities with better amenities, says Dr Satheesh Kathula, president (2024-25) of the American Association of Physicians of Indian Origin.

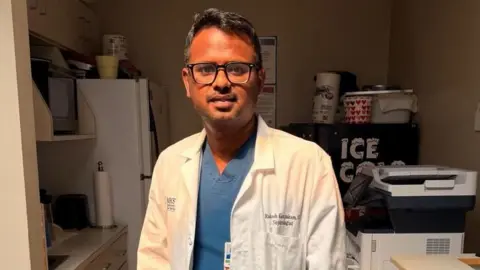

Rakesh Kanipakam

Rakesh Kanipakam

Dr Rakesh Kanipakam travels hundreds of miles every week to treat patients with failing kidneys

Economics widens the gap as wealthy urban hospital systems easily outbid the struggling rural ones by offering better salaries, adds Geeta Minocha, a Stanford medical student raised in rural Florida.

So any hike in the fee would make it harder to bring in new clinicians from abroad, putting additional financial pressure on rural hospitals that are already stretched thin, experts say.

And it’s not just remote towns. The country’s capital Washington and several states, including Michigan, New Jersey, Florida, New York and California, rely heavily on immigrant physicians, who comprise more than 30% of the doctors there.

In his book, Immigrant Doctors: Chasing the Big American Dream, Dr Kathula tells several stories of Indian medical graduates in the US who did their work at the cost of their own welfare.

“They have died serving our country during the HIV crisis of the 1980s-1990s when laboratory staff were reluctant to even draw blood, and during the recent Covid-19 pandemic,” he says. “I know doctors who were treating patients here but could not travel to attend their own parents’ funeral in India during the pandemic.”

Many of these professionals started arriving in the 1960s when the US opened its doors to fulfil surging demand, attracting thousands of highly trained doctors from developing nations such as India.

Most of them enter the US on J-1 visas for clinical residency training.

After completing their medical residency, they either switch to H-1B visas if a willing hospital sponsors them or must return to their home country as per the terms of the J-1 visa (which requires them to go back for at least two years before applying again).

In 1990, to fix acute doctor shortages, the US government created an exception. It waived the two-year return requirement for doctors willing to work in Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSA) – regions where there are not enough doctors to meet the population’s healthcare needs. This waiver – the Conrad waiver – gives foreign doctors the opportunity to continue working in the US on H-1B visas tied to serving in HPSA areas once their clinical training on J-1 visa ends.

One such HPSA is deep inside south Alabama, where Dr Rakesh Kanipakam, a doctor trained in the southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, travels hundreds of miles every week to treat patients with failing kidneys.

“We serve clinics in three cities, five countryside clinics and dialysis centres in a 100-mile radius,” he says. “The entire place had just one nephrologist but now even he is retiring.”

Foreign medical workers also contribute millions of dollars to the US economy.

Back in Batesville, Dr Anantha’s colleagues credit him for transforming their hospital into a centre of excellence.

In a letter written in support of Dr Anantha’s green card application, the hospital CEO said the doctor had bolstered the facility’s financial stability by over $40m annually and has also brought them many awards in the field of healthcare.

For now, the AMA says it is feeling “encouraged by the administration’s openness to an exemption”.

But Dr Mukkamala warns that action on this needs to happen quickly “because international medical graduates are determining their next steps now and the possibility of this fee hike could deter highly qualified physicians from working in the US”.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, X and Facebook.