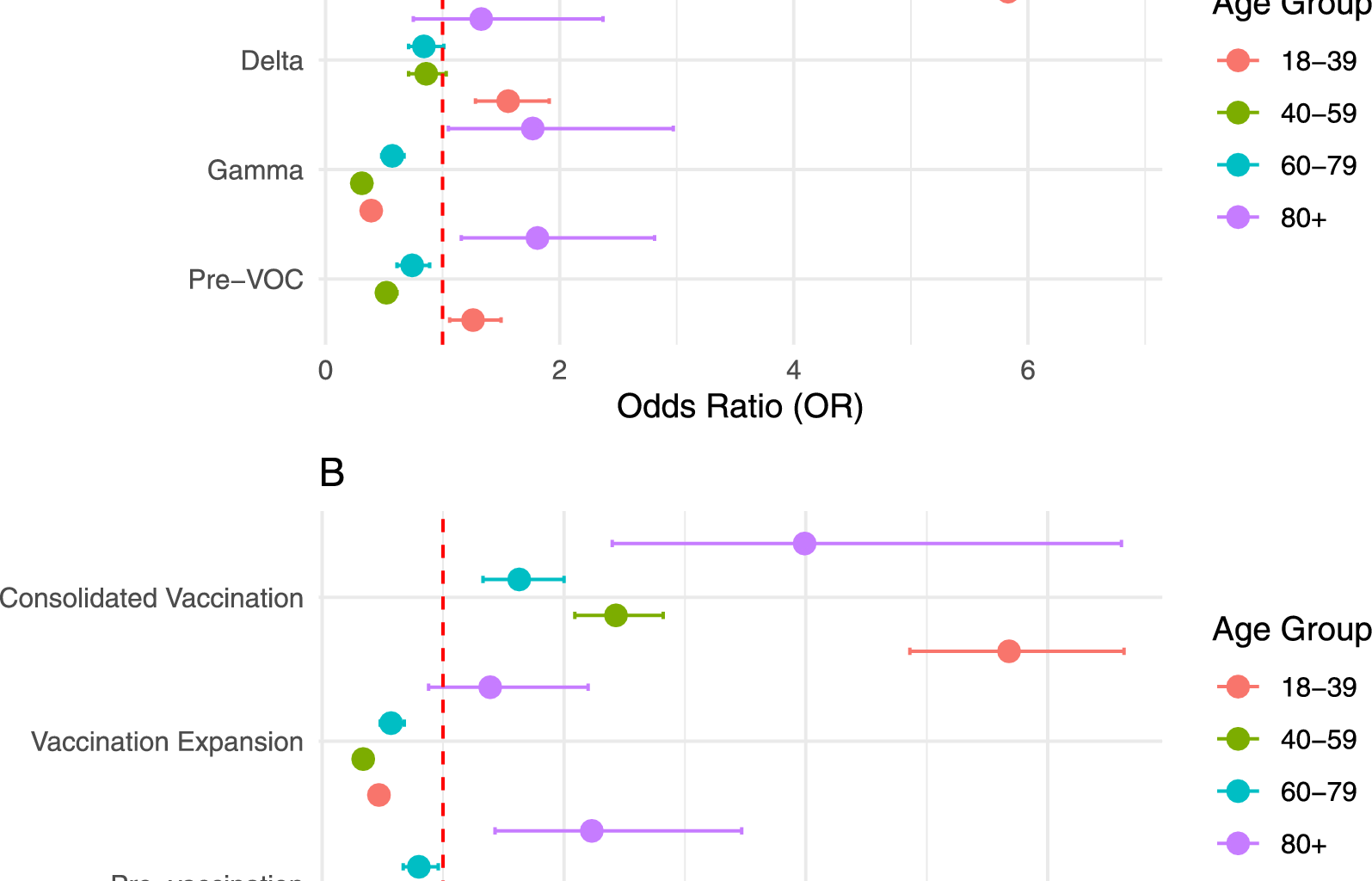

In this study, we demonstrated the association between HIV infection and COVID-19 death in the Brazilian population from 2020 to 2022, considering different periods of dominance of variants of concern and vaccine rollout. Additionally, our study identified age group as an effect modifier of HIV on COVID-19 mortality. Age is the primary determinant of COVID-19 mortality in the general population, with several studies highlighting a substantially higher risk of death in individuals over 65 years of age [35,36,37,38]. However, when it comes to PLWHA, the relationship between the risk (or odds) of death and age is reversed [39]. Our findings indicate that in the general population, the effect of age on COVID-19 mortality was evident, with the odds of death increasing with age across most periods (Supplementary tables 4–5). By contrast, older adults living with HIV (80+ years) had higher odds of COVID-19 death during all periods of variant dominance. Similarly, younger PLWHA, aged 18–39, showed higher odd of COVID-19 death during the pre-VOC, Delta, and Omicron periods.

Evidence in the literature regarding the association between HIV and COVID-19 death is heterogeneous and divergent, with few studies considering the dominant variant or vaccination coverage. While initial studies conducted with small groups during the pre-VOC variant dominance period suggested no increased risk of severity or mortality from COVID-19 among PLWHA [11, 40,41,42], an analysis of a cohort comprising data from 17,282,905 adults in the United Kingdom found that, during the pre-VOC period, PLWHA had an almost threefold higher risk of COVID-19 mortality (HR = 2.90; 95% CI: 1.96–4.30) compared to the HIV-negative population [43]. Similar results were identified in a cohort of 204,583 COVID-19 cases recorded by the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene during the pre-VOC period, where COVID-19 mortality was 1.62 times higher among PLWHA [44].

Our results demonstrated that only PLWHA aged 18 to 39 and those in the oldest age group had higher odds of death from COVID-19 during the pre-VOC period. In contrast, PLWHA aged 40–79 showed lower odds of death from COVID-19 compared to individuals without HIV in the same age group during the same period. However, it is important to note that the interaction between age and HIV was not investigated in the referred studies.

It is important to highlight that there was a high variation in case fatality rates among the different VOCs worldwide, with the Beta variant having the highest case fatality rate at 4.19%, followed by the Gamma variant at 3.60%. The Alpha and Delta variants had case fatality rates of 2.62 and 2.01%, respectively, while the Omicron variant had the lowest case fatality rate at 0.70% among all variants [45].

During the dominance periods of VOCs, conflicting results have been reported regarding COVID-19 mortality among PLWHA. Some meta-analyses have found a higher risk of mortality among PLWHA compared to the general population, particularly during waves preceding Omicron [46,47,48,49], while others found no significant differences [11, 40].

These divergences may stem from methodological limitations, such as the absence of sensitivity analyses considering the dominant VOC, as well as heterogeneity in the populations and periods analyzed. Notably, one of the largest international multicenter studies, conducted by the WHO Global Clinical Platform, found that PLWHA had consistently higher mortality risks across the pre-Delta, Delta, and Omicron waves, with the highest risk observed during the Omicron wave [10].

In our study, the dominance of the Gamma variant, with a worldwide case fatality rate of 3.60% [45], was associated with lower odds of death among PLWHA across most age groups, except for those over 80 years. By contrast, the highest odds of death among PLWHA were observed during the Omicron dominance period, despite this variant having the lowest case fatality rates in the general population [45]. These findings suggest that the differential impact of VOCs on PLWHA may reflect the interaction between altered immune responses and variant-specific characteristics, such as immune escape and virulence. The widespread use of antiretroviral therapies (ARTs), particularly regimens containing tenofovir and lamivudine, may also have provided protective effects for their potential inhibitory action on the SARS-CoV-2. In Brazil, tenofovir and lamivudine are part of the preferred first-line ART regimens [50].

The variation in the odds of death among PLWHA during different periods of VOC dominance also underscores the influence of contextual factors such as vaccination coverage. Vaccination coverage, which is inversely related to case fatality rates [45], likely played a significant role in shaping COVID-19 mortality outcomes. Notably, the periods of VOC dominance coincided with vaccine rollout phases, suggesting that part of the observed effect may be attributable to vaccination levels rather than the variants themselves [45]. In our study, during the vaccination expansion period, the odds of death were lower among PLWHA for all age groups, except for the oldest adults. Notably, PLWHA were prioritized for COVID-19 vaccination alongside older adults, individuals with comorbidities, and other immunocompromised groups. During the consolidated vaccination period, which overlaps with the Omicron dominance, having HIV was associated with higher odds of death in all age groups, with the most notable increases observed in the 18–39 and 80+ age groups.

Even though PLWHA may have lower seroconversion rates, particularly among those with lower baseline CD4+ counts or higher viral loads [51], evidence shows that after a booster dose, immune response rates become similar to those of HIV-negative individuals [52]. However, this response varied depending on the dominant VOC, with lower immune responses observed against the Omicron variant [52]. Additionally, fully vaccinated PLWHA have been shown to have a higher risk of COVID-19 diagnosis and death compared to HIV-negative individuals [53, 54].

These findings underscore the necessity of integrating the specific vulnerabilities of PLWHA into public health planning and policy formulation for pandemic response and other health emergencies. The identification of distinct mortality patterns among PLWHA across different pandemic periods suggests that universal strategies may be insufficient to ensure equitable protection for this population. Therefore, future emergency response guidelines should incorporate tailored approaches for PLWHA, including sustained prioritization for vaccination, enhanced monitoring of immune responses, uninterrupted access to antiretroviral therapy, and the integration of HIV care into broader pandemic response strategies. These measures are essential to mitigate the disproportionate impacts observed and to ensure a more equitable and effective public health response in future crises.

The results of this study revealed a heterogeneous impact of HIV on COVID-19 mortality across Brazil’s federative units, characterized by an inverse relationship between the average odds of COVID-19 death in the population and the effect of HIV on mortality. States with higher average odds of COVID-19 death tended to exhibit a reduced impact of HIV, suggesting that contextual factors unique to each location significantly influence these outcomes.

Regional disparities in social conditions and healthcare access across Brazil’s five geographic regions further explain these variations. The highest odds ratios for COVID-19 death among PLWHA were observed in the North and Northeast regions, where the disease burden remains significantly higher compared to the Southeast and South [55]. This disparity persisted and even intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the North [56]. Although studies on COVID-19 mortality among PLWHA in Brazil remain scarce, existing analyses are concentrated in the Southeast. A cohort study conducted in São Paulo during the early phase of the pandemic found no increased risk of COVID-19 mortality among PLWHA, suggesting that comorbidities, rather than HIV status itself, were the main determinants of severe outcomes [57]. However, while comorbidities have a well-established impact on COVID-19 mortality, it is important to note that their prevalence is consistently higher among PLWHA compared to the general population and may act as mediators in the relationship between HIV and COVID-19 outcomes rather than confounders, potentially underestimating the independent contribution of HIV to COVID-19 mortality risk.

Research in the Southeast region identified a case-fatality rate of 34% among PLWHA with severe acute respiratory syndrome, with social vulnerabilities playing a significant role in mortality risk [58]. Other study highlighted the impact of the pandemic on HIV care, demonstrating that linkage and retention strategies helped mitigate disruptions in treatment access [59]. The only nationwide assessment comparing hospitalized COVID-19 patients with and without HIV found a higher in-hospital mortality rate among PLWHA in 2020, though this difference was no longer observed in 2021 [60]. However, this analysis did not account for regional disparities, dominant SARS-CoV-2 variants, or vaccination coverage, all of which may have influenced the observed outcomes. To our knowledge, our research is the first to analyze COVID-19 mortality among PLWHA at the national level in Brazil, incorporating data from all federative units while also accounting for the influence of variant dominance and vaccination coverage over time.

Several limitations must be acknowledged in this study. First, it was not possible to estimate the effects of other sociodemographic variables such as race/ethnicity on the odds of COVID-19 death among PLWHA. This is particularly relevant given the well-documented racial and regional health disparities in Brazil, both before and during the pandemic period [61,62,63,64,65]. Although we adjusted for sex, age, and state of residence, which we believe was sufficient to control for major confounding, this approach does not fully capture the intersectional vulnerabilities that may exist. Nonetheless, the consistency of our results with the current understanding of HIV epidemic trends and regional disparities in Brazil supports the validity of our findings [61,62,63]. Additionally, this analysis incorporated a multilevel model that included contextual factors and accounted for local disparities, providing a more robust approach compared to standard methods. Moreover, the interaction between HIV status and age group was identified, further strengthening the model’s capacity to reflect the complexity of these associations.

Another limitation concerns the classification of vaccination periods. While this categorization was necessary to analyze the COVID-19 Mortality in PLWHA over time, it does not fully capture the heterogeneity in vaccine coverage at the individual or regional level. Vaccination rollout in Brazil was not uniform, with significant state-level variation in both access and adherence, which may have influenced the association between HIV status and COVID-19 mortality. Although the multilevel modeling approach accounted for regional disparities by including the state of residence as a random intercept, some degree of bias due to vaccination delays or differences in accessibility across states cannot be ruled out. Future studies incorporating more granular data, such as state-level vaccine coverage or individual vaccination status, would enhance model interpretability and analytical precision.

In this research, we were concerned about the potential misclassification of individuals’ HIV status in the death certificate due to underreporting, which could introduce a misclassification bias of the exposure. To mitigate this issue, we examined all mentioned causes of death, identifying HIV status based on the presence of ICD-10 codes for HIV/AIDS in any field of the death certificate rather than relying solely on the underlying cause of death. This approach, previously employed in studies on causes of death in Brazil [66, 67], aimed to capture all individuals with a documented HIV diagnosis. By incorporating multiple fields from mortality records, we sought to reduce underreporting and ensure a more comprehensive identification of PLWHA. However, the comparator group in our analysis, comprising the general population, may include PLWHA who were not diagnosed or not reported on death certificates. This inclusion may further attenuate the observed differences in mortality between groups. Any residual error from misclassification is likely non-differential, which would lead to an underestimation of the exposure effect on the outcome. Therefore, the odds ratios obtained in this study may be somewhat underestimated.

Finally, the absence of clinical and laboratory data such as comorbidities, viral load, CD4+ count, and ART adherence limits our ability to assess how key clinical factors may act as confounders or mediators, thereby restricting the strength of causal inference in our findings.

In summary, this study contributes to the understanding of the impact of COVID-19 pandemic among PLWHA in Brazil and provides a basis for future analyses. Further research should include individual-level data on viral load, CD4+ counts, and ART adherence to better understand the clinical factors associated with increased COVID-19 mortality risk among PLWHA. Stratified analyses by race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and comorbidities will be essential to clarify the role of social disparities in shaping vulnerability to COVID-19 among PLWHA. Additionally, studies focusing on the Brazilian context, considering its regional specificities, are crucial due to the uniqueness of the country’s geographical, sociodemographic characteristics, and healthcare system.