Regarded by many as one of the finest songwriters in the American canon, and a distinctive urban storyteller beyond compare, Tom Waits has long been hailed for his chronicles of the dispossessed, and his characterful deep-throated vocal style.

From 1973’s inaugural LP Closing Time to 2011’s Bad as Me, Tom Waits’ body of recorded work has been cherished and cited by many of music’s key figures. He remains the very personification of the authentic, outsider musician, living and breathing the ramshackle ethos that is imbued within his records.

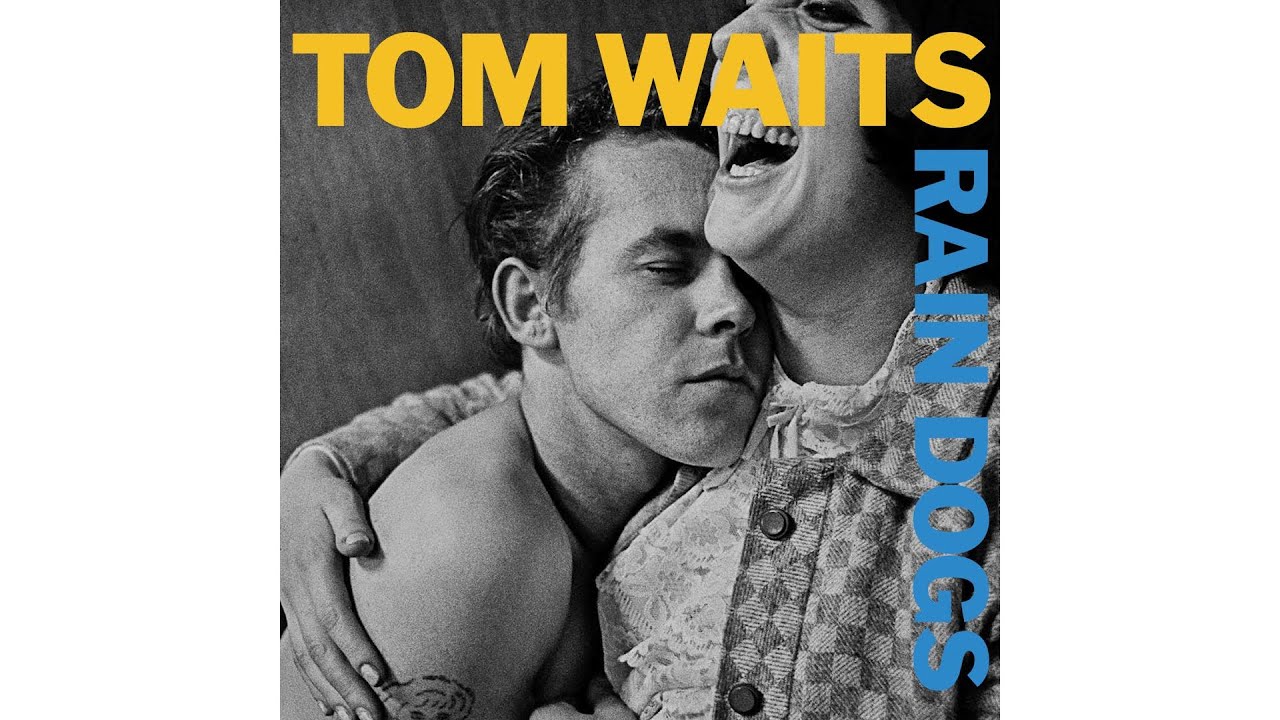

For many Waits-heads, it’s his mid-eighties trilogy that marked his first major label records; Swordfishtrombones, Rain Dogs and Franks Wild Years, that are pointed at as his most musically engrossing period.

Self-produced by Tom, the records corralled a troupe of some of the finest (and most flexible) musicians in Waits’ phone book. Thematically, the songs sharpened his ongoing focus on misfits and outsiders, and were housed within some of the most fascinating and inventive arrangements of his entire career.

You may like

Lyrically, the trilogy lifted the rock on a shabby sub-strata of American inner-city society. These were songs that made protagonists of the homeless, the alcoholics, the drug-dependent and the rootless travellers that Waits saw around him upon moving to New York.

The high-points of this three album-journey are many – Underground, 16 Shells From a Thirty-Ought-Six, Jockey Full of Bourbon, Singapore, Downtown Train and Way Down in the Hole (later to become the iconic theme of revered TV series The Wire), documented a sprawling interconnected community – rippling with characters, murky locations and – framed at the centre of it all – Tom himself, making poetry from the beautiful ugliness of this miscreant underclass.

The trilogy has been humorously described by some as Waits’ ‘rags to rags’ narrative.

(Image credit: David Corio/Redferns/Getty Images)

It’s the second album, 1985’s Rain Dogs, that most cite as the strongest part of the trilogy, and a firm contender for the greatest record of his career.

Directly inspired by his move from California to New York, Waits processed this shift by penning a series of new songs which vividly painted what he saw.

With encouragement from his wife Kathleen Brennan, Waits felt that his change of locale should also be represented by an expansion of his musical palette. Out went the bar-room piano that dominated earlier albums, and in came… a chest of drawers.

As he built out his new songs, Tom would occasionally put down his guitar and head out into the streets. Using a small hand-held cassette recorder, he’d capture the hustle and bustle of NY’s ambience, as well as snatches of conversation, and moments in time that suggested the world of the new album.

“[Rain Dogs refers to] people who live outdoors. You know how after the rain you see all these dogs that seem lost, wandering around. The rain washes away all their scent, all their direction. So all the people on the album are knit together, by some corporeal way of sharing pain and discomfort,” Waits told You Magazine.

Rain Dogs’ tales of of New York’s destitution and depravity were backed by diverse arrangements befitting Tom’s vision. A veritable ‘junkyard orchestra’ of unlikely instruments peppered the new album, alongside more experimental approaches that were influenced by New York’s colourful avant garde scene. Percussion, in particular, was wrought from cups, wooden block and even chests of drawers.

Rain Dogs’ sinister opening track Singapore presented the most blatant example, Waits recalled that the aforementioned chest of drawers was pummelled to oblivion when used as percussion during the recording process.

“On the last bar of the song the whole piece of furniture collapsed and there was nothing left of it. That’s what I think of when I hear the song. I see the pile of wood.”

You may like

Tom Waits – “Singapore” – YouTube

Waits later recalled more specifics of the drawers’ destruction in an interview with KCRW-FM, “[Singapore] is an adventure song. I like adventure songs and I always remembered that in the studio the drum sound that we used was a two by four attacking somebody’s chest of drawers. [The] whole song played and all the backbeats were played with a two by four hitting the chest of drawers repeatedly and on the last bar of the song the whole piece of furniture had collapsed and there was nothing left of it and the song was over. That’s what I think of when I hear the song. I see the pile of wood and it excites me.”

Supported by the alternative-enabling Island Records, Rain Dogs found Tom operating on a wholly unique level that rejected the more technologically-focused production processes of his mid-80s contemporaries, and instead looked backwards to the homespun, ’that’ll do’ attitude of his jazz and blues influences, as well as outward to more exotic instrumental approaches of genres across the globe.

This had begun during the recording of the trilogy’s initial entry in 1983, Swordfishtrombones. Prior to making that record, Hollywood soundtrack producer Emil Richards became instrumental (in more ways than one) in helping Waits expand his percussive language, bringing into the studio a range of exotic percussion that included dabuki drum, African talking drum, marimba, bell plate, and the bizarre antique, ‘glass armonica’ – first invented by Benjamin Franklin.

“I’ve always been afraid of percussion for some reason,” Waits told Rock Bill Magazine in 1983. “I was afraid of things sounding like a train wreck, like Buddy Rich having a seizure. I’ve made some strides; the bass marimbas, the boobams, metal long longs, African talking drums and so on.”

“I see the pile of wood and it excites me.” Never leave Tom Waits alone with your household furniture (Image credit: Paul Natkin/Getty Images)

On Rain Dogs, this wider percussive assortment was performed by Michael Blair, and its presence served to allude to the various multicultural facets of New York’s subcultures, as well as the tension, paranoia and danger that permeated the city.

It was accompanied by a far looser jazz ensemble, including stand-up bass (performed at various points by Larry Taylor, Greg Cohen and Tony Garnier) and saxophone (performed by Ralph Carney), as well as banjo, trombone, accordion and harmonium.

The results of this unusual enmeshing of sounds formed a riveting listen. There’s the unsettling wonkiness of Cemetery Polka, the late-night mournfulness of Tango Till They’re Sore, the frenzied mania of Midtown and the bluegrass slink of the banjo-led Gun Street Girl.

On the album, drummer Stephen Hodges was asked to approach his beat playing non-traditionally. Waits demanded he shun the cymbals and think more tribally – focussing on the toms over all else. A good example of this toms-favouring approach can be heard on the rickety Hang Down Your Head.

Tom Waits – “Hang Down Your Head” – YouTube

“I can count on one hand and have a couple of fingers left over the number of single notes like ding, ding, ding I played on a cymbal with Tom Waits,” Hodges was quoted as saying by The Music Aficionado. “He not only did not want a jazz trio, he did not want to hear a drum playing in that sibilance. He let marimba take over the 8th notes which was a really cool move.”

After presenting the rough skeleton of the new songs in their basic state to the assembled group of musicians on his ‘ratty old hollow body’ guitar, and indicating the type of groove he was after, Waits pushed his cabal of instrumentalists to think outside of their comfort zones as they concocted their parts of the arrangement.

In terms of the record’s diverse musical landscape, Waits revealed – to British newspaper The Mail on Sunday that he purposefully sought to reject advances in recording technology in pursuit of his own homegrown sounds.

“If I want a sound, I usually feel better if I’ve chased it and killed it, skinned it and cooked it. Most things you can get with a button nowadays. So if I was trying for a certain drum sound, my engineer would say: ‘Oh, for Christ’s sake, why are we wasting our time? Let’s just hit this little cup with a stick here, sample something, take a drum sound from another record and make it bigger in the mix, don’t worry about it.’ I’d say, ‘No, I would rather go in the bathroom and hit the door with a piece of two-by-four very hard.’”

“If I want a sound, I usually feel better if I’ve chased it and killed it, skinned it and cooked it”: Never leave Tom Waits alone with your sounds (Image credit: Brian Rasic/Getty Images)

Of his increasingly dexterous vocals – now regularly orienting themselves within his signature growly register, Waits was equally as exploratory. “I’ve tried singing through pipes and trumpet mutes, singing into drinking glasses, cupping your hands, things that have been done before,” Waits told GQ Magazine in 1987, “You can call up a lot of these sounds through technology, but I’m discovering that if I find something myself and nail it to the wall, then it’s mine.”

It was also on Rain Dogs that Waits first worked with versatile blues guitarist Marc Ribot. “He’s big on the devices. Appliances, guitar appliances,” Waits was quoted as saying. “He has this whole apparatus made out of tinfoil and transistors that he kinda sticks on the guitar. Or he wraps the strings with gum, all kinds of things, just to get it to sound real industrial. It’s like he would take a blender, part of a blender, take the whole thing out and put it on the side of his guitar and it looks like a medical show.”

There was also another guitarist in the wings, one Keith Richards. Yes, the Rolling Stones legend lent some deliciously whisky-soaked licks to the record’s growling blues-in-a-shack brute, Big Black Mariah, as well as tracks Union Square and Blind Love.

“He’s very spontaneous,” Waits said of Richards in an interview with Beat Magazine. “He moves like some kind of animal. I was trying to explain Big Black Mariah and finally I started to move in a certain way and he said, ‘Oh, why didn’t you do that to begin with? Now I know what you’re talking about.’ It’s like animal instinct.”

“Rain Dogs was my first major label type recording, and I thought everybody made records the way Tom makes records,” Ribot was quoted as saying in the book On Waits. “I’ve learned since that it’s a very original and individual way of producing. As producer apart from himself as writer and singer and guitar player he brings in his ideas, but he’s very open to sounds that suddenly and accidentally occur in the studio.”

(Image credit: Paul Natkin/Getty Images)

Though commercially, Rain Dogs stalled in the outer reaches of the Billboard chart, it was this period of Tom’s career, and Rain Dogs in particular, that would be revisited by many of music’s future innovators, and celebrated as an important piece of work.

It was an album on which Waits sought out new sounds not in new technology but from behind dusty old pianos and within antiquated furniture (that he’d gleefully smash to smithereens if the song called for it.)

It established Tom as a creative unafraid of wandering far from the fenced-in conventions of genre, and bringing in sounds from across the musical aisle.

An ardent fan was Radiohead’s Thom Yorke, who has expressed his love for Rain Dogs on numerous occasions. “Every track was a short movie set in a mysterious, circus-like down-at-heel America that I had almost no understanding of, with different characters both in the lyrics and the instruments, an entire universe revealed to me for a few minutes only to drop me at the other end of the block – no idea how I’d got there,” Yorke told The Guardian.

“This record has never got tired for me.”