A budget tracks your income and expenses — money in, money out. It may help you make some adjustments in order to live within your means and save for the future, whether that means a down payment on a house or car, or putting your kids through school.

The goal, of course, is to spend wisely and avoid high-interest debt (read: credit card balances). And to do that, you need to have basic information and a wee bit of discipline.

Here’s are some things to know:

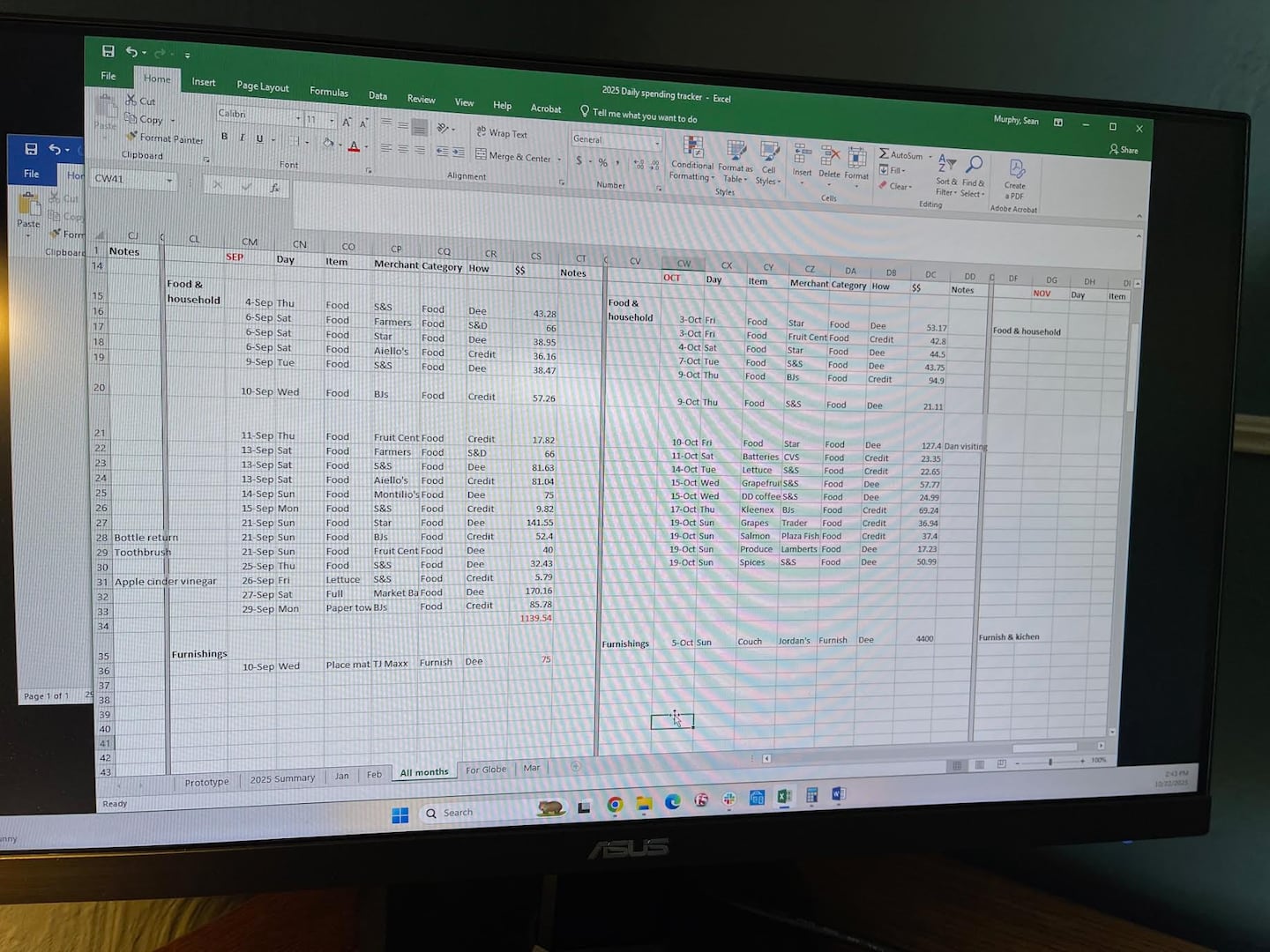

I track my monthly spending (my wife’s, too) almost daily in an Excel spreadsheet set up with 18 categories such as apparel, food, insurance, media, restaurants, transportation, and utilities. (Your categories may differ.) Some of my categories show no spending in some months (home furnishings and vacation travel, for example), while others always have many entries (food, media). My goal is to account for every dollar spent, which is called zero-based budgeting.

I bring home paper receipts after almost every transaction (I let them pile up in a drawer). I then type into my spreadsheet the amount spent, along with the date, merchant, and other specifics. I also add a note to some expenditures for future reference. When I receive my monthly checking and credit card statements, I compare them with what I’ve got in my spreadsheet to make sure I haven’t missed anything. (I rarely use cash.)

What good does all that do?

It allows me to compare how much we spent on each category monthly. I recently noticed the increasing cost of video streaming services such as Netflix and Hulu, which prompted me to switch to cheaper plans (alas, with ads).

You might opt for a budgeting app such as You Need A Budget or Mint to help.

Globe columnist Sean P. Murphy tracks his and his wife’s spending in an Excel spreadsheet.Sean P. Murphy

Globe columnist Sean P. Murphy tracks his and his wife’s spending in an Excel spreadsheet.Sean P. Murphy

First, determine your income. Calculating “gross” pay — what your employer pays you before taxes and other deductions — is fairly straightforward, unless your pay varies or you have more than one job. But most of us are salaried and or wage-earning employees and our “take home pay” is total pay minus money withheld to pay state and federal income taxes.

What else comes out of my paycheck?

Your paycheck also gets dinged for Social Security (6.2 percent) and Medicare (1.45 percent). Both are matched by your employer on your behalf. These are known as “payroll” or FICA taxes, but strictly speaking they’re not taxes. They are more like contributions toward benefits paid to seniors.

Many of us pay for health care insurance (and sometimes dental or vision) with deductions. Some taxpayers (including me) save a few bucks by using Flexible Spending Accounts, which are offered by employers. That lets you set aside money every pay period to cover out-of-pocket health care costs, like deductibles, copayments, and prescriptions with “pre-tax dollars.”

So what’s left after taxes?

It’s often referred to as disposable income — earnings you get to decide how to spend (sort of). One popular budgeting framework is called the “50-30-20″ rule, which suggests you spend 50 percent of disposable income on “needs,” 30 percent on “wants,” and 20 percent on savings and debt repayment (excluding mortgage and auto loans). There is nothing magic about “50-30-20.” The goal isn’t to hit those exact percentages; it’s to gain a working knowledge of your own personal finances.

Housing, transportation, food, and utilities. For those who own, housing costs include mortgage, real estate taxes, homeowners insurance, and homeowners association fees, if applicable. You should also budget for upkeep of your house. For the last 10 years, I have spent many thousands of dollars to replace the boiler and some drafty windows and doors (nondiscretionary) and remodel the kitchen and add a deck (discretionary).

How much should I spend on housing?

Some experts suggest spending no more than 28 percent of disposable income on your mortgage. Under the 50-30-20 rule, that would leave 22 percent of your disposable income for other housing expenses (real estate taxes and insurance, for example) transportation, food and utilities. Of course, everyone’s circumstances are different and change over time. When I was younger, with children in school, for example, many worthy house projects went undone.

How much should I spend on rent?

A widely used guideline for those who rent suggests your rent should not exceed 30 percent of gross income. A significant portion of Boston area renters, however, are considered “cost-burdened” because they spend a higher percentage on housing, sometimes approaching 50 percent or even more.

A “for rent” sign seen at a Brookline apartment building in September. David L Ryan/ Globe Staff

A “for rent” sign seen at a Brookline apartment building in September. David L Ryan/ Globe Staff

Things you can live without if you had to, such as entertainment (dining out, streaming services), vacations, and non-essential shopping for things like clothing, gadgets, and electronics.

What are “savings and debt repayment”?

You should have enough money in an emergency fund to cover up to six months of essential expenses. But your savings should go beyond that. Some experts recommend that you “pay yourself first” by automatically saving a portion of your paycheck. Employer-based 401(k) plans are a prime example, with the additional benefit of saving on taxes.

OK, so what is “debt repayment”?

Very few of us are debt-free. But there are different kinds of debt. Borrowing money to buy a house or condo or a motor vehicle may be considered “good” debt. You use your house and car over multiple years and should pay for them over multiple years, with a mortgage or other loan.

What kind of debt isn’t advisable?

Credit cards are almost indispensable these days for good reason: They are safe, pay rewards, and give you a tidy record of your spending. I put just about every purchase on a credit card. But I pay the balance monthly without fail. You should, too, if at all possible.

What’s the downside of credit card debt?

Credit card debt is by far the most expensive form of consumer borrowing (it’s “bad” debt). Paying 20 percent interest on thousands of dollars of debt month to month is like subsidizing the banks that provide credit cards. You can do much better with a home equity or personal loan, assuming you have a decent credit rating. (Maintaining a budget may help you pay your bills on time and thus improve your credit score.) Make a plan to pay off credit card debt, even if it will take years. Also, avoid “buy now, pay later” offers to avoid possible steep fees.

What about using generative AI for advice on spending?

I would advise caution. A recent survey found that more than half of those who acted on the financial advice offered by ChatGPT or other generative AI apps said they had made a poor financial decision or a mistake in trying to follow the guidance.

Got a problem? Send your consumer issue to sean.murphy@globe.com. Follow him @spmurphyboston.