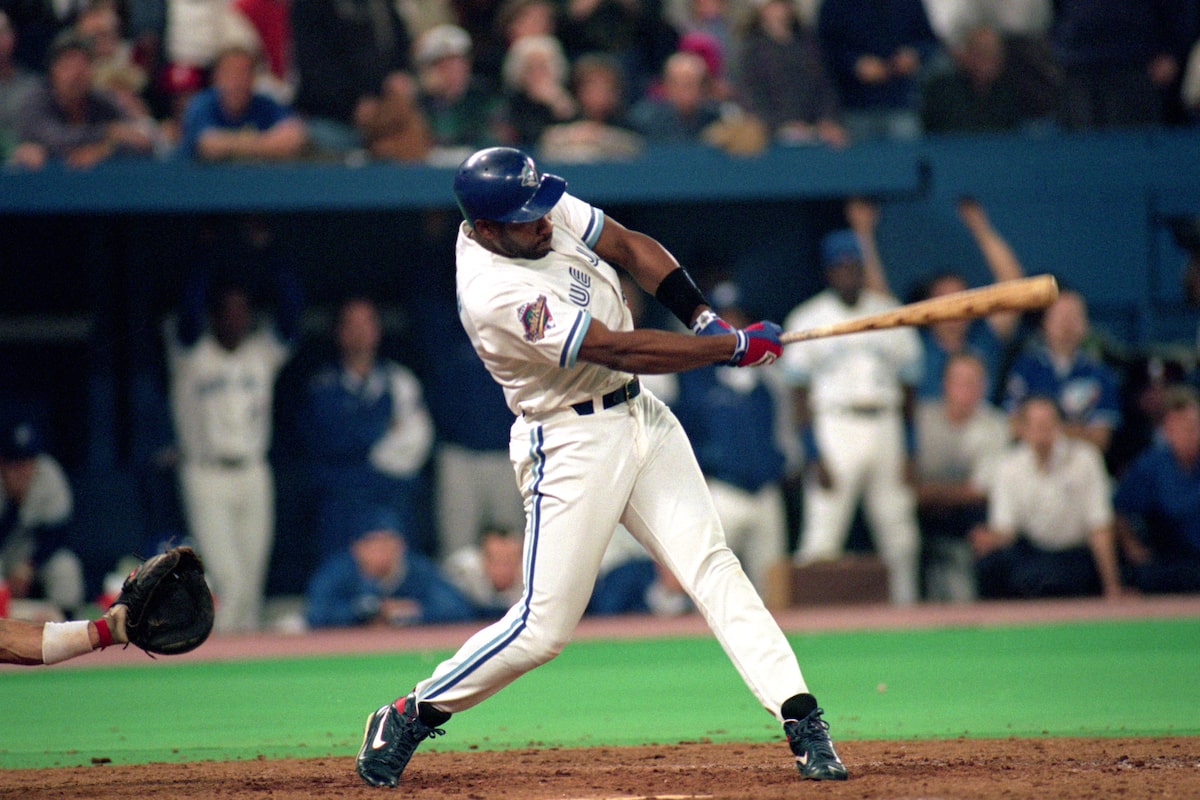

Joe Carter’s 1993 World Series home-run trot may be the defining visual of the moment, but Tom Cheek’s ‘Touch ’em all’ call came over the radio waves.Rick Stewart/Getty Images

It’s no coincidence that many of baseball’s greatest moments have been immortalized by radio broadcasters. There’s a special kinship between the sport and the medium that has endured improbably to this day.

When Joe Carter hit his championship-clinching home run in Game 6 of the 1993 World Series, it was play-by-play man Tom Cheek of CJCL who implored the slugger to “Touch ‘em all, Joe!”

There has never been a bigger call in Canadian baseball history – maybe the Jays have something special in store for us against the Dodgers – and it didn’t happen on TV.

Radio play-by-play man Tom Cheek called every Blue Jays game – 4,306 in a row – from April 7, 1977, to June 2, 2004, according to the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame.The Canadian Press

There’s a curious romance to baseball on the AM dial. By all rights it should have gone the way of the radio play, but instead fans across generations still rhapsodize over its peculiar qualities. Baseball is the most listened to sport on the radio by some margin, according to Nielsen, although the game’s hold on the broader culture continues to weaken. It’s an odd phenomenon – as if a significant share of the population still preferred silent films to talkies.

For card collectors, the ritual is worth more than the asset

MLB’s Field of Dreams game is another example of baseball’s history of mythmaking

What we’re dealing with is a happy marriage of medium and message. The sounds and rhythms of baseball just mesh organically with the technology of radio broadcasting.

A ball game on the radio is the sound of summer: syrupy slow, punctuated by bursts of excitement, the static and drone of the crowd mimicking the roar of cicadas in the trees. Maybe you’re in a car with the windows down. Maybe listening on a screened-in cottage porch. What you’re hearing is time being deliciously stretched, like a length of taffy.

Baseball is a game that can be appreciated, like radio, while doing something else: washing the dishes, driving home from work. Decisive action is rare enough, and loudly enough announced, that your ear will inform you when something has happened. The ubiquity of baseball in summer, a three-hour game almost every day, makes it the pleasant white noise of the season, the emotional equivalent of the CBC perpetually crackling in the kitchen.

It helps that the soundscape of the sport is easy on the ears, mellifluous through even the cheapest car speakers. It’s a game of sweet, crisp percussion as vivid as the first bite of an apple in autumn (if your team is lucky enough to still be playing then): the thwack of pitch hitting mitt, the crack of bat on ball. It’s a game that purrs, then pops.

By comparison, the squeak of sneakers on hardwood, the slush-slush of blades on ice and the militaristic barking at a line of scrimmage are cacophonous.

The pace of baseball synchronizes with radio just as smoothly. It is a slow, suspenseful game, and fans are forever imagining what will come next. Baseball plays out in the mind’s eye almost as much as it does on the field, even for those in attendance – even for the players. New York-based Irish author Colum McCann once described the air at a baseball game as having that “chewy sense of hope,” and with so much for the imagination to chew on, radio’s lack of real images is not much of a drawback.

If it all sounds a bit quaint, that’s also part of the appeal. Baseball is a nostalgia-drenched sport, and radio is a living link with its hallowed past.

On Oct. 3, 1951, Bobby Thomson of the New York Giants hit a home run against the Brooklyn Dodgers in the so-called ‘Shot Heard Round the World’ – heard, of course, on the radio as called by Russ Hodges.The Associated Press

Both the sport and the technology shared a golden age that roughly coincided with America’s, the middle decades of the 20th century.

In fact, the apotheosis of baseball on the radio can be given an exact date: Oct. 3, 1951, when Bobby Thomson hit his Shot Heard ’Round the World at Manhattan’s Polo Grounds, with Russ Hodges on the call: “The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! … They’re going crazy! They’re going crazy!”

(A single fan tape-recorded the game, the only reason Hodges’s call survives.)

The moment was so emblematic that the great American novelist Don DeLillo used it as the opening set-piece of his masterpiece Underworld, told partly from the perspective of the radio booth. DeLillo appreciated Hodges as a fellow wordsmith, noting how the broadcaster laid “a heavy decibel” on the word “strike” to build tension on the pitch before the home run and how he paused to let the crowd noise register, reminding himself to let “the drama come from them.”

Even after the conquest of TV, radio guys continued to capture the game in a unique way, with an artistry all their own.

Think of Vin Scully calling the anxious ninth inning of Sandy Koufax’s perfect game, featuring “29,000 people in the ballpark and a million butterflies,” the mound in Dodger Stadium transformed into the “loneliest place in the world.”

On April 14, 1969, the Montreal Expos played their inaugural game at Jarry Park.Archives de la Ville de Montréal

The great Canadian journalist and baseball writer Tom Hawthorn (a family friend) still remembers experiencing the first-ever Expos game in 1969 while stuck in his Montreal Catholic school.

“A kindly nun allowed one boy in our class to listen to the action with an ear plug on a portable radio kept in his desk. He gave us half-inning updates.” The enthusiasm of Dave Van Horne (with his famous “up, up, and away!” home run call) and the understated elegance of Russ Taylor would keep Hawthorn hooked to his own portable radio for years to come.

Kids may be more likely to smuggle smartphones into class today, but baseball as an audio medium has survived, largely thanks to the car. If you’re stuck in cottage-country traffic or your evening commute, the boys of summer can still keep you company.

The success of the 2015 Blue Jays, heard by many fans on the radio, was punctuated by Jose Bautista’s home run in Game 5 of the ALDS at Rogers Centre on Oct. 14.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Tori Smith, a big Jays fan, followed the thrilling 2015 season on the radio while driving her son to sports practices all over the city.

“I found it both engaging and relaxing, with occasional bursts of excitement,” she said. “With baseball there’s time to chat, which is nice when you’re at a game and also when you’re listening on the radio. The broadcasters can fill in those slower minutes with baseball history, player stats, mini-lessons on strategy or rules. And because so much of the pleasure of baseball is in its lore and the minutiae of rules, there’s always something to talk about and listen to.”

The marriage of baseball and radio has weathered its storms, and the pair now sit serenely together like an old couple on a porch swing, with a recent survey finding that 12 per cent of Americans listened to a baseball game on the radio last year. (The data is harder to come by for Canada.) The old connection between medium and message is still coming through loud and clear.

And who knows which player may have to be reminded over the airwaves to touch ’em all this year.

Editor’s note: The caption accompanying Tom Cheek’s photo previously said that he called every Blue Jays game until June 2, 2024. His streak ended June 2, 2004.