I grew up in the 2000s, so it might be a surprising statement when I say that much of my introduction to the internet, technology, and gaming came from Internet Relay Chat, also known as IRC. As a kid, I had no idea that IRC was already an incredibly important piece of internet history. It dates back to the 1980s, predating the World Wide Web itself, and was the brainchild of a Finnish student named Jarkko Oikarinen. As it turns out, real-time group chats were in existence years before web browsers and AOL existed, and decades before Discord, Slack, or WhatsApp.

Through my teenage years (and a bit before), I spent a lot of time on the likes of PurpleSurge (thanks to the Serebii #SPP channel), QuakeNet, and EFNet, speaking to people from all over the world. It was there that my love of technology truly flourished, and there are people from those servers that I still know and speak to to this day.

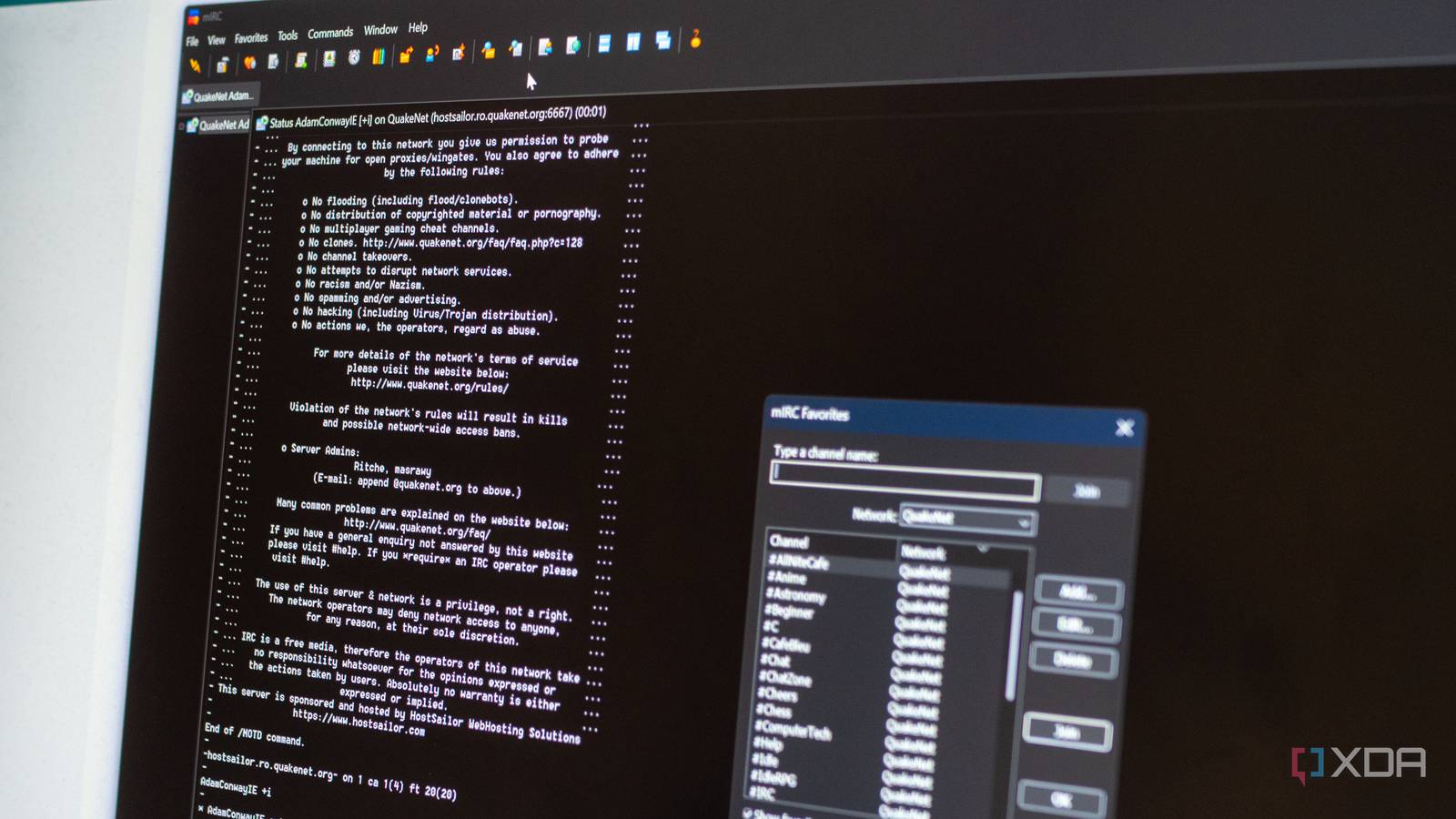

In those days, I spent long hours on both CLIRC on my Nintendo DS and mIRC on my computer, learning to script with mSL and playing chat-based games like Werewolf. I met some incredible people, and while nowadays I use services like Discord (as do many others), it doesn’t feel the same. Many of these services can attribute a lot of their lineage to IRC.

The history of IRC in brief

It all started in Finland

It helps to know where IRC came from to truly appreciate its global and profound influence. Invented by Jarkko “WiZ” Oikarinen at the University of Oulu in Finland in August 1988, his goal was to replace MultiUser Talk, a BBS chat, to enable real-time conversations between multiple users at once. It quickly gained popularity, spreading from Finland to universities and institutions across the world. By the middle of 1989, there were 40 IRC servers deployed worldwide.

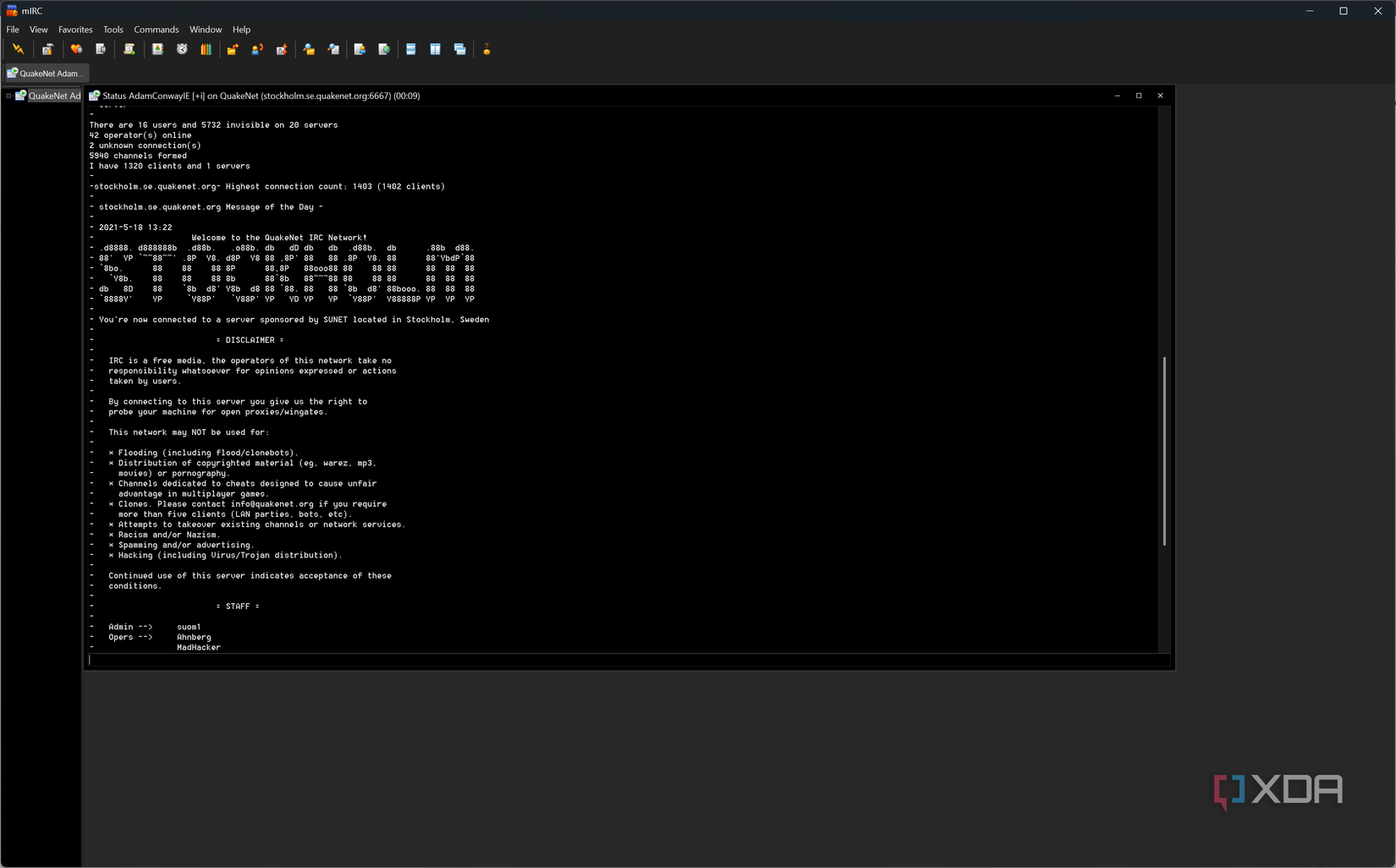

Within just a few years, partially thanks to the announcement of the World Wide Web by Tim Berners-Lee in 1991, IRC grew exponentially. In the early 2000s, millions of users were on IRC, and large networks formed, entirely run by volunteers. Networks such as EFNet, Undernet, DALnet, and more served massive communities. QuakeNet, one of the networks I frequented, became the world’s largest chat network back then, and its peak was measured on February 8, 2005, with a mind-bogglingly large 243,394 users.

However, in the mid-2000s, IRC began its decline. More mainstream users shifted to web-based forums, instant messengers, and eventually social media. Between 2003 and 2012 alone, IRC networks collectively lost around 60% of their users. In other words, by the time I was using IRC, it was already well past its prime. There were still hundreds of thousands of users on IRC across the globe, mind you, but the writing was already on the wall for those who had been paying attention to it.

Despite the decline, IRC never truly died off. It persisted as a beloved tool in certain communities, especially among open-source developers, gamers, and hobbyist groups. That’s how I got started, as there were many gaming groups that I was a part of that all primarily communicated through IRC. Even today, there are still many development-related channels on the biggest IRC servers, and many open-source projects still use it as a communication method, too.

From its inception to its heyday in the early 2000s and beyond, IRC has been what can only be described as an undercurrent of the internet. Many of the most ubiquitous services found today have at least some of their routes in IRC or the associated “services” that could be rolled out, a bit like plugins (though they were often bots), such as NickServ, ChanServ, SpamServ, and more.

Life on IRC

I grew up with it

As someone who played a lot of Pokémon growing up, I came across Serebii. That site aimed to serve a niche subset of Pokémon players who wanted to keep up to date with the games, play with others, and battle and trade. The main chat room on Serebii was called #SPP (standing for Serebii’s Pokémon Page) on the PurpleSurge network. I remember at the time it felt like a limitless clubhouse of sorts, as I remember looking at the channel list and finding other topics that appeared interesting, too.

The thrill of IRC was, in a sense, the welcoming community that it boasted. PurpleSurge was a relatively small, tight-knit network, so you’d often see the same nicknames every day and build friendships with people. There were entire games you could play through chat as well, and it was incredible to join a channel with some friends and play a game of Werewolf or have a random conversation with someone across the globe about the minute differences between my country and theirs.

Not only that, but given the time that it was, emoji wasn’t really a thing. It was just text and the occasional ASCII face. In hindsight, it was a pretty formative social experience; clear communication over text was important, and I spoke to people from all walks of life, differing massively in personality. From the good, the bad, and the… weird, you met a lot of different people.

QuakeNet was an entirely different vibe: it had thousands of channels, some with hundreds of users at any given moment. It could (and did) feel chaotic for a newcomer. I’d join a channel for a popular game, and the chat would move so quickly that it was hard to keep up. In a sense, I guess it felt like I had moved from a small rural town to the very center of Times Square.

In order to deal with the scale of these channels, there were often channel operators, or “ops,” along with “half-ops.” These were denoted by an @ or a % before their name, respectively. They could kick or ban users (and trust me, they did), or set a channel “mode” that would change how the channel worked. These could include disabling nickname changes, only allowing registered users to speak, or filtering out messages containing certain words.

Each channel was basically a self-governing community with its own set of norms and enforcers. You had to read the rules, pay attention to the channel topic, and respect the channel operators. If you didn’t, you might end up on the receiving end of a /kick (requiring you to sheepishly rejoin) or even a /ban. It may sound draconian in a sense, but back then, it was the way a massive community had to be policed.

Honestly, at the time, IRC was essentially my social media. I could play games with people, chat about random topics, and try out new things. I even remember one friend showing me how to set up an internet radio stream, so that I could share music with friends while we were chatting.

IRC had its limitations

None of the fancy features of Discord or Slack

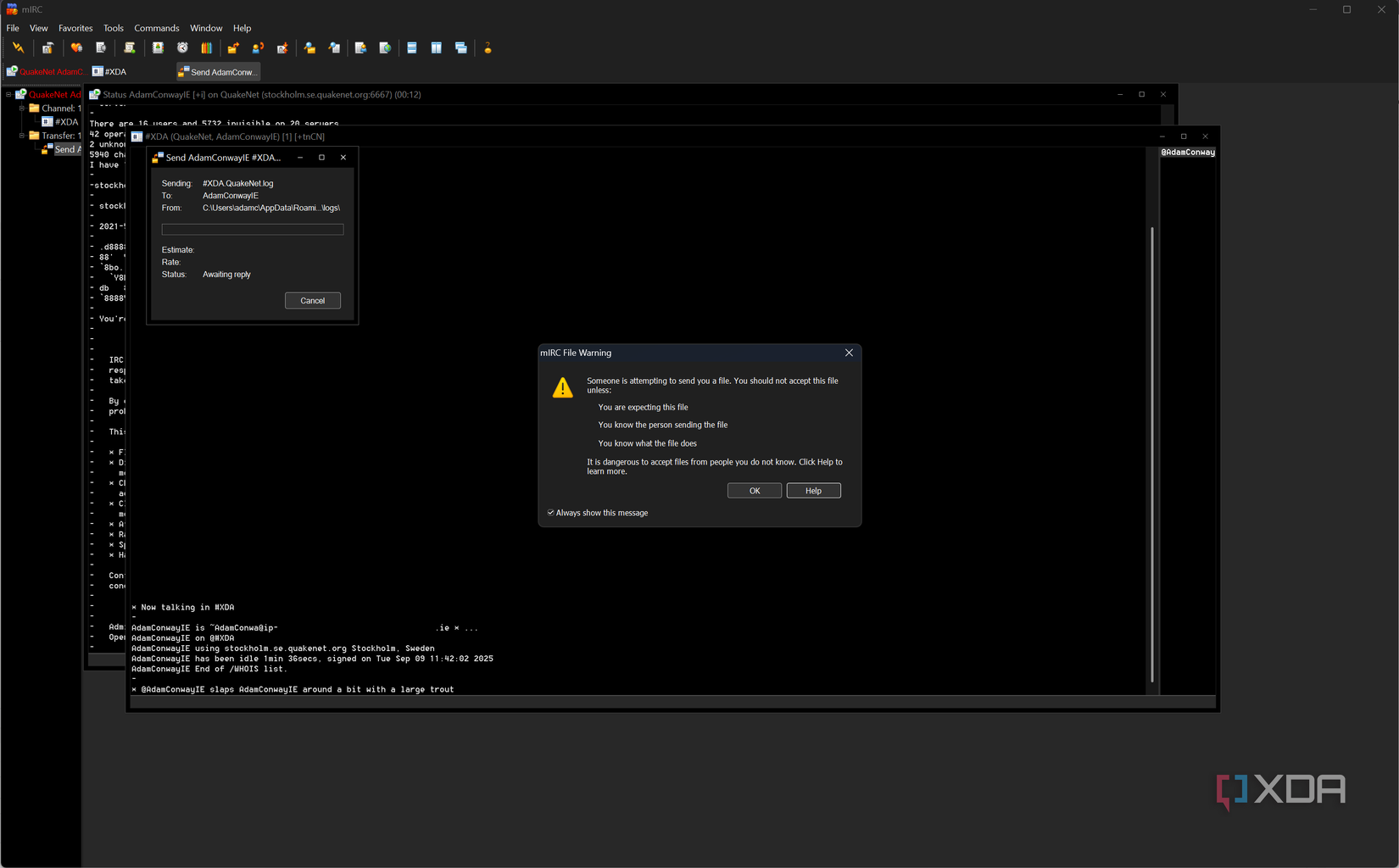

Compared to the tools we use today, IRC had a lot of limitations. Fragmentation was a natural part of the experience, and you’d often go to another server and register a friend’s nickname before they could join, just to be annoying. Sharing images wasn’t possible without using IRC’s DCC (Direct Client-to-Client), or CTCP, so that you could send a file to a friend, and this meant hosting the image somewhere and pasting the link instead. Even Markdown, found across the web (and in note-takers like Obsidian), has its roots in older web-based services and how people naturally added emphasis and structured messages over text, and that includes IRC.

One of the hardest-to-imagine aspects of IRC, assuming you never used it before, was the lack of message persistence. If you weren’t connected to an IRC channel, you missed everything that was said. Most servers didn’t log messages or allow you to see what had happened in the past, meaning that if you joined a channel, you had no clue what they were just talking about. It was often good etiquette to be silent when you first joined, just to see what the current ongoing conversation was.

Of course, modern platforms have totally flipped this, and the likes of Slack and Discord retain chat history that you can scroll up and read what people said while you were offline. In the IRC days, people came up with solutions for this lack of persistence. One common tool was setting up a bouncer (BNC) or using a shell account: essentially a program that stays connected to IRC all the time on your behalf, keeping logs of channel activity, and you can connect your client to it to see what you missed. I used one of these briefly on a Linux server, though given how young I was, I undoubtedly set it up wrong.

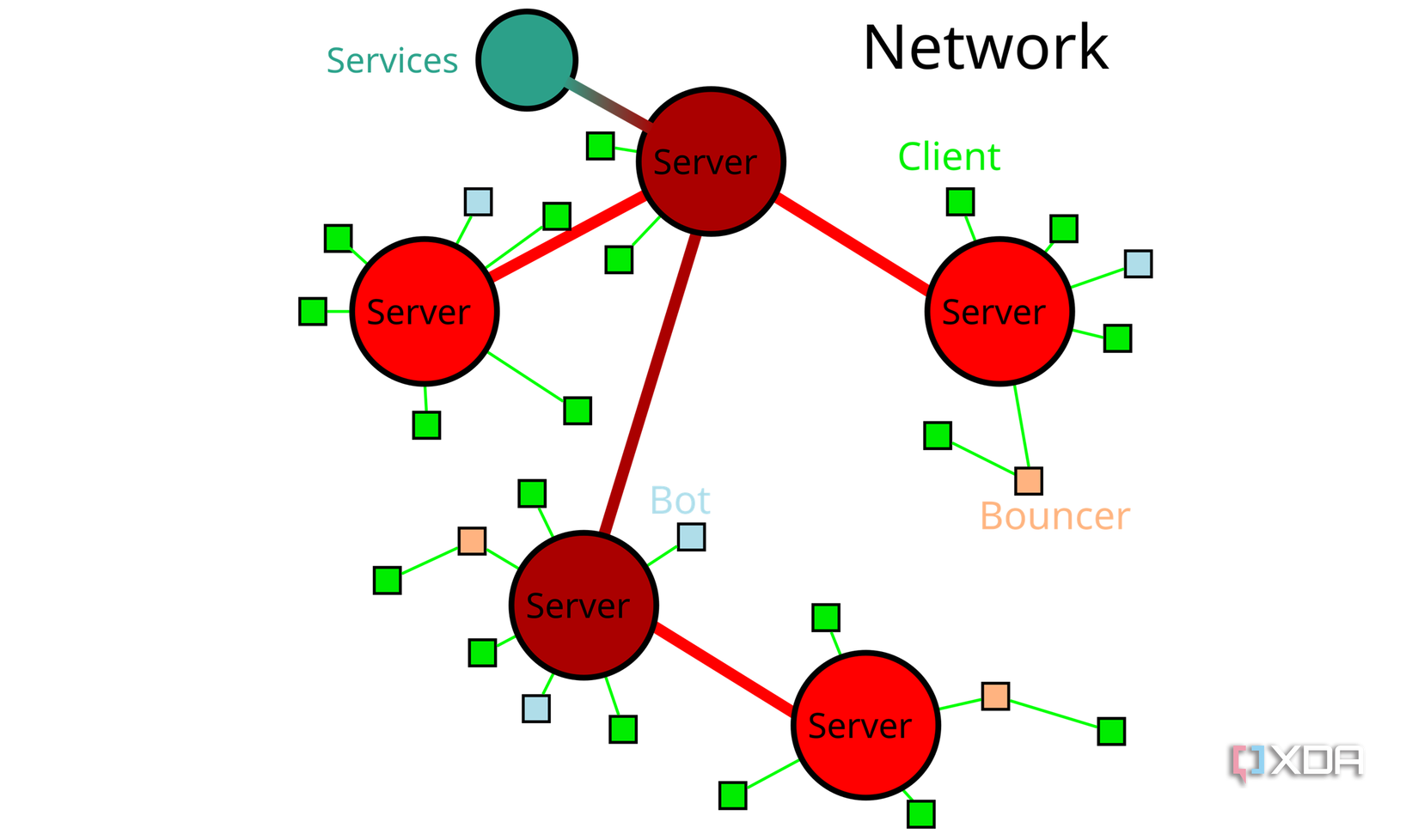

There was one other phenomenon that can happen on modern services, but usually doesn’t, and that’s what was called a “netsplit.” IRC has no central server; instead, it links together a set of distributed servers in a mesh of sorts. This design was great in that networks could grow by adding more servers, but a breakdown in communication between two servers would result in a netsplit. Users on one side couldn’t see users on the other, and you’d see everyone on the other side quit the channel all at once. When it was repaired, they’d all flood back at once, too. I remember experiencing this and being on a side with significantly fewer people connected, and having a conversation with people that I didn’t really speak to that much in that group.

There are, of course, many other unique aspects to IRC that you won’t find on any modern service, but that was part of the appeal. It was text only, quite robust (given that a netsplit still kept you online), and fun. I’d personally argue that the likes of Discord and Slack are just IRC wrapped up in a neat UI with some bells and whistles tacked on, while also handing over control to a for-profit company with a vested interest in advertising and collecting data.

mIRC bots introduced me to programming

A scripting language with a clear purpose

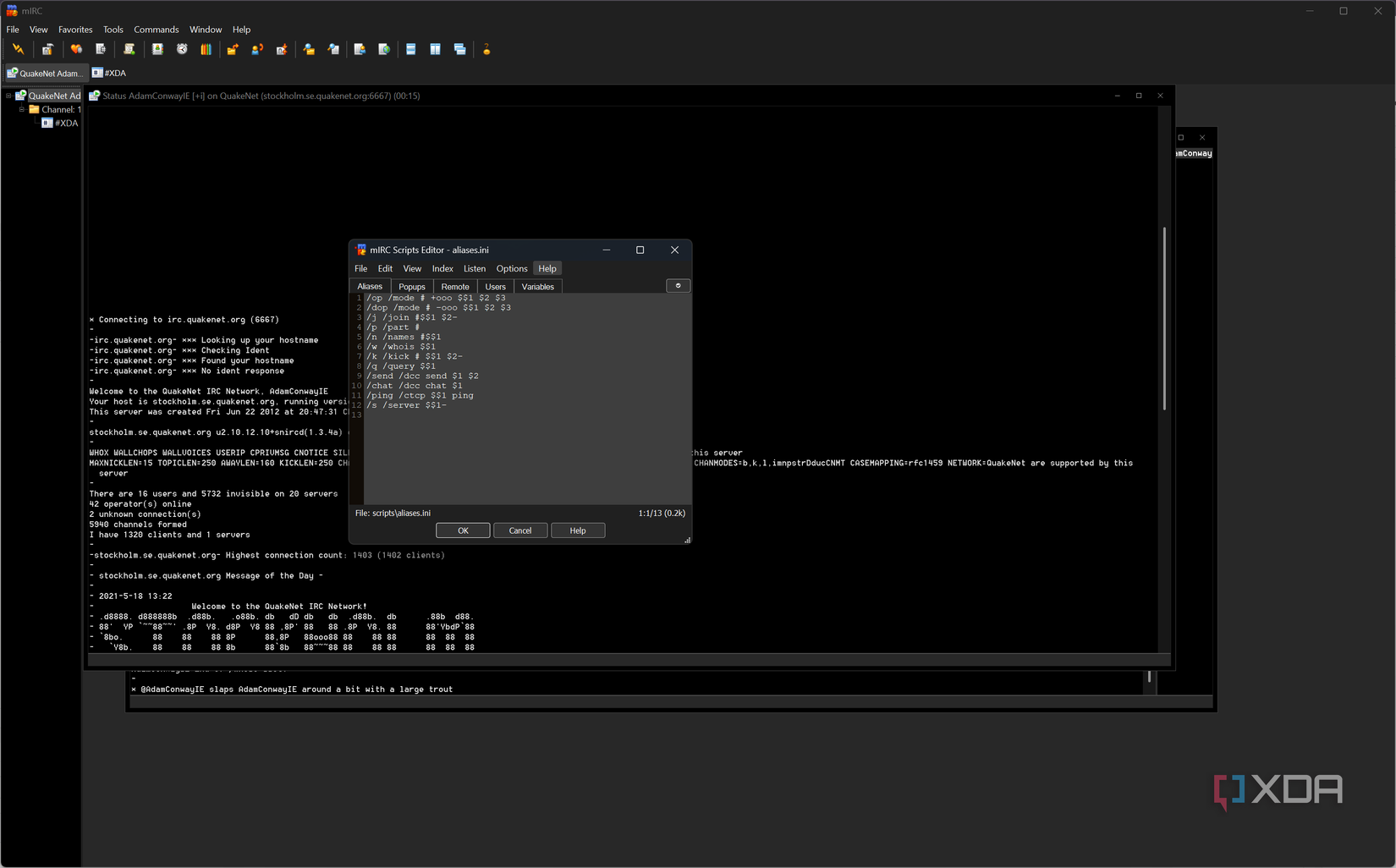

On IRC, it was common to encounter or deploy automated helper programs, referred to as “bots.” They could do everything from managing a chat room to playing games or spouting jokes, and they were my first true experience with programming. I had played around with BASIC at this point, but unlike BASIC, which saw me create simple programs for the purposes of learning, miRC Scripting Language (mSL) had a purpose from my younger viewpoint.

One of the most famous IRC bots is Eggdrop, and it’s still actively developed today. An Eggdrop bot is basically a small program you run on a server that connects to IRC 24/7 with a certain nickname, and its primary job is to sit in your channel and enforce rules or provide utilities. You could script Eggdrop in Tool Command Language, or Tcl, to respond to custom commands. There was an entire “bot culture” of sorts, and QuakeNet’s “Q” bot was an integral part of the network.

mIRC, though, is really where I spent my time developing on IRC. mIRC was ubiquitous, and it meant that any user could write snippets of code in mIRC to respond to events, thanks to its event-driven and procedural language. I spent endless hours in the mIRC script editor writing little tools for fun, and some of them got quite complicated. Oh, and just like you would find today in many modern languages and programs, injection attacks were possible then, too.

on *:TEXT:Hello!:#:{ msg $chan Hello, $nick $+ ! }

The above code example is what mSL looked like, and this particular line sees a “Hello!” in a channel and replies back with “Hello, (nickname)!” It’s simple, but you could build pretty sophisticated bots in just mIRC if you were dedicated enough. There were entire script packages like NoNameScript, ircN, ExCuRsIoN, and so much more.

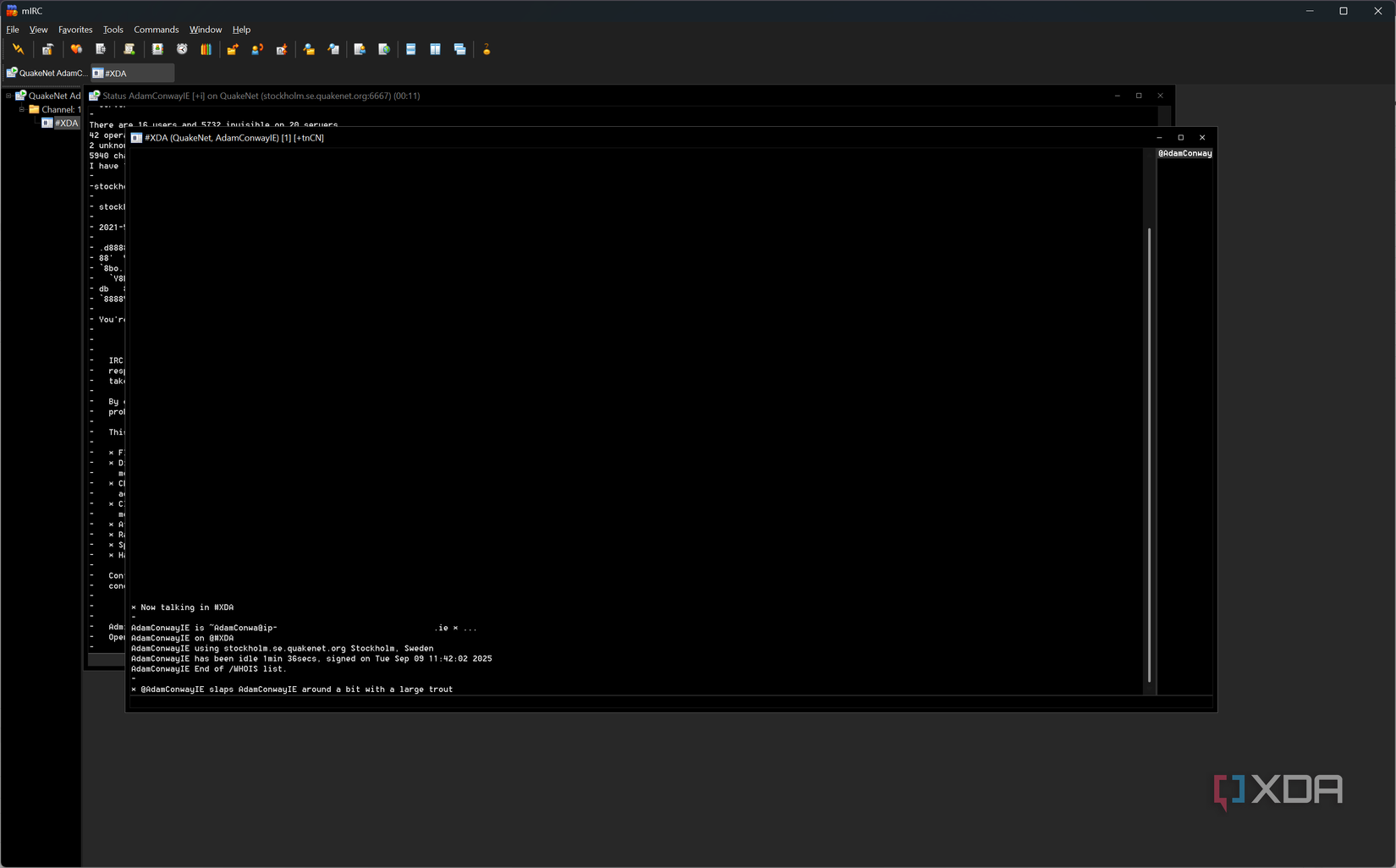

Source: Basshunter

A fun bit of lore with mIRC: you may have seen someone say something like “(name) slaps (name) around a bit with a large trout.” This originates from the mIRC command /slap, which in itself was inspired by a Monty Python sketch. Customizing miRC back then was a lot of fun, and you could do all kinds of things with it.

IRC, and mIRC by extension, were hugely influential in the early days of the internet. Funnily enough, “Boten Anna” by Basshunter (which was an earlier form of Basshunter’s ‘Now You’re Gone’, though an entirely different song lyrically) was written about an IRC bot called “Anna,” who turned out to be a real person. The music video even shows the mIRC client, and you can see Basshunter typing in a QuakeNet channel. An entire pop song about IRC? Discord could never.

There were so many bots back then that people would pick and choose from to deploy in a channel. Infobots, where one could define a term, quote bots for saving funny moments, and relay bots to bridge entire channels across two servers to allow for intercommunication, were all quite common, and nowadays similar tools exist for all kinds of platforms. In a sense, these were the earliest forms of Discord bots.

The internet was directly influenced by IRC

Most modern services have something to thank IRC for

Many aspects of the modern internet come from IRC, or at least started with IRC. Chris Messina, an early adopter of Twitter and widely credited as the creator of the hashtag, suggested it as a “grouping” method, inspired by IRC’s “#channel” format. From Carnegie Mellon University:

Messina came up with the concept of the hashtag for Twitter after thinking about how the symbol was used in Internet chat (IRC) to indicate the name of a chat room.

“It seemed to me that appropriating something that was already used elsewhere would increase its chances of adoption, rather than promoting something completely new,” he said.

As for services such as Twitch, the underlying protocol powering its chat is IRC. This dates back to its justin.tv days, and even now, you can connect with an IRCv3-compatible client using an approved bot for chat moderation. This is slowly being phased out, but it works. It makes sense, too, as individual streaming channels and their chat rooms are analogous to IRC and text channels.

As for Slack, it adopts quite a lot from IRC, too, and even hosted an IRC gateway (and XMPP) until 2018. Sure, it has persistence and a fancy GUI, but it maintains channels, mentions, one-on-one chats, and even slash commands. The company even acknowledges this:

When it came time to build Slack, we wanted to capture the best parts of IRC in the context of running a business

When it comes to bots in chatrooms, those also date back to IRC. Eggdrop and Infobot walked so Twitch’s Nightbot and Slack’s Slackbot could run. Obviously, modern bots can do way more, but they also follow a trail that was first carved out and embarked upon in the 90s.

Finally, when it comes to Discord “servers,” the IRC influence is very clear. The individual channels are just like channels on an IRC server, and practically every chat tool in that vein uses “channels” as a way to differentiate between topics — complete with a hashtag, too.

To the average person who never touched IRC, the influence might be invisible. But across internet culture, tools, and the everyday services we know and love (or tolerate), the similarities are undeniable. It was a massively influential tool for building communities, and nearly two decades after its peak, it still feels like nothing out there manages to best IRC in terms of simplicity. There’s no algorithm deciding what you see, no message reactions, just humans exchanging text.

On a personal note, IRC taught me a lot. Learning to type quickly (to keep up with fast channels), communicating clearly over text, and speaking with people from all over the world and from all kinds of cultures were all things I picked up on IRC. My first programming experiences were on IRC, and there are people I still speak to that I met on IRC.

If you’ve never tried IRC, it’s still out there waiting for you. It may feel empty compared to the messaging tools of today, but over time, you may find that to be the appeal.