Imagine the year is 2050 and the world has devised a way to stop global warming. No, not by doing the hard work of cutting greenhouse gas emissions, but by spraying reflective particles into the stratosphere that dim the sun. The strategy works: temperatures at ground level stabilise, and life goes on as normal despite escalating carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere.

Until suddenly, something goes wrong. The spray guns break down, the money runs out, a pandemic hits or a global war disrupts operations. Whatever the case, the planet starts to heat up, fast, as years of pent-up emissions kick into effect. Ecosystems can’t cope, wildlife perishes en masse, societal chaos ensues.

This disastrous scenario and similar science fiction-sounding situations like it have been named “termination shocks” by climate scientists. But what most people don’t realise is that, over the past few years, we’ve been experiencing a version of it firsthand.

Global action to improve air quality – by shutting down coal-fired power stations and cleaning up shipping fuels – has saved millions of lives in recent decades. But on the flip side, air pollution can also cool the planet. Removing it has released a surge of warming that has warped the weather around the world.

Thanks to advances in climate modelling, we are now starting to understand the true impact of our drive for cleaner air on lightning storms, heatwaves and ocean ecosystems. What’s more, these changes could be a taster of what termination shocks of sci-fi proportions would look like. “It definitely provides a preview of what could happen,” says Tianle Yuan at NASA.

Curbing air pollution

If you wound back the clock to 2012 in China, you would find a country choked by poor air quality. There were more than a million deaths a year from cases of stroke, heart disease and lung cancer that were linked to particulate matter pollution. Public anger over the issue was mounting, with huge, violent protests erupting across the country.

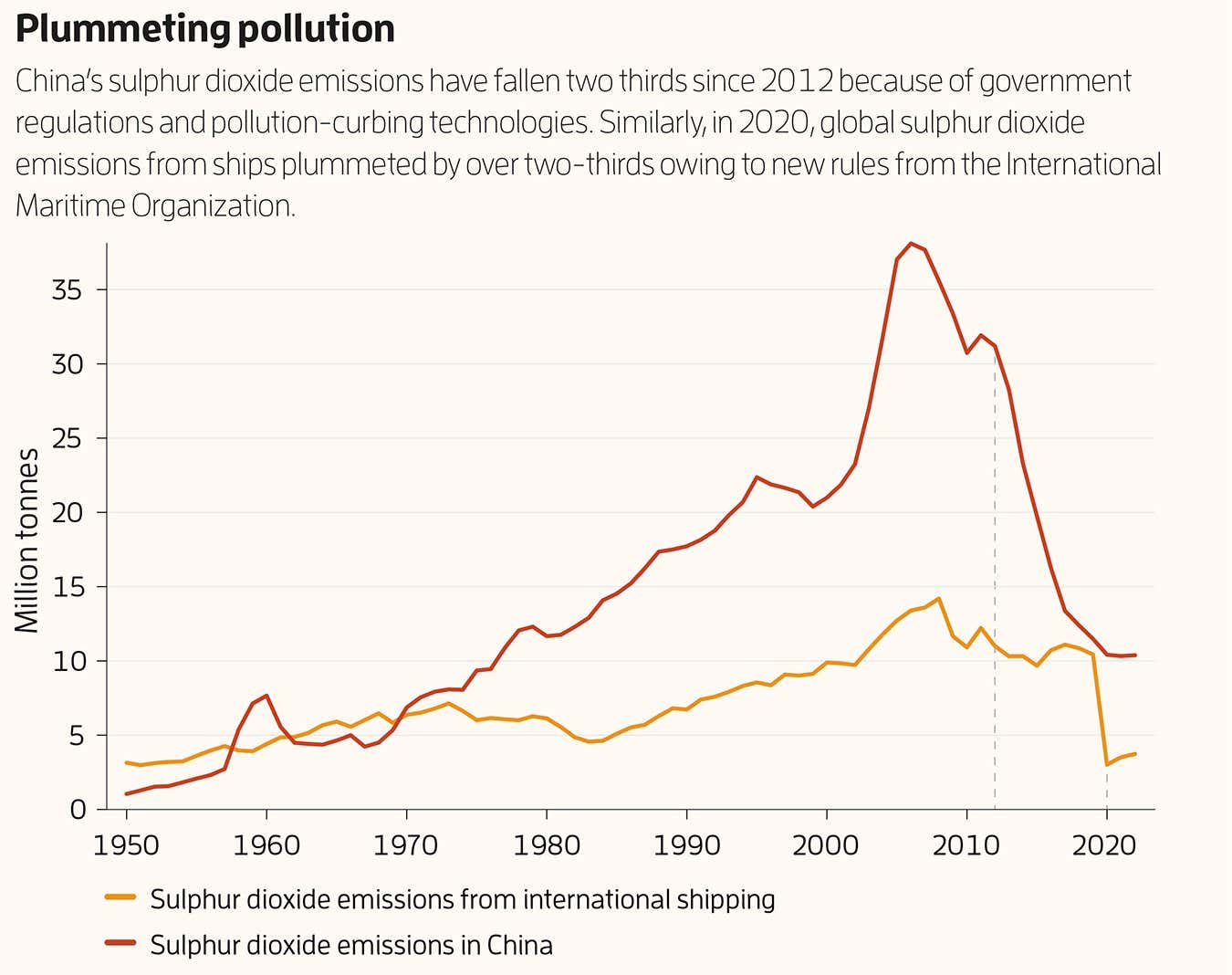

The government was forced into action, imposing strict pollution controls on power plants and industrial sites and promoting renewable energy development over coal-fired power. It led to a rapid and dramatic drop in the rates of particulate matter and sulphur dioxide pollution, with emissions down by half and two-thirds, respectively, since 2012. In a similar vein, in 2020 the International Maritime Organization (IMO) introduced new rules on emissions from ships, curbing the amount of sulphur dioxide pollution ejected over smoggy port cities and the open oceans by over two-thirds that year.

Community Emissions Data System 2024

These actions have saved millions of lives, improved public health and curbed environmental problems like acid rain. But there’s a catch: sulphur aerosols help to cool the planet. This happens in two main ways: first, they behave like tiny mirrors, reflecting sunlight back into space. Second, they act as nuclei for the formation of condensation droplets, helping to make clouds denser and whiter, and so more reflective. “If the number of aerosol particles is increased, it leads to a greater number of droplets, and the overall droplet surface area increases, resulting in a greater reflection of sunlight,” explains Robert Wood at the University of Washington.

Climate scientists have known about this cooling effect since the 1970s. It has helped to dampen the warming effect of greenhouse gas emissions by about 0.5°C, they estimate – although uncertainty ranges are large.

So it isn’t surprising that our efforts to improve air quality have come with a side order of extra global warming. Actions to reduce pollution in East Asia alone account for 5 per cent of global temperature increase since 1850, a study published earlier this year shows.

Extreme weather shifts

What has startled climate scientists is how some parts of the world have experienced unusual, even extreme responses at a regional level to the removal of aerosol pollution. But thanks to improvements in climate models, which are now able to simulate these effects, we can understand in unprecedented detail how such efforts provoke hotspots of warming and changes to extreme weather around the world.

There are now fewer lightning strikes over shipping lanes, for instance, which is thought to be because there are now fewer aerosol particles from ships’ smokestacks to generate electrically charged ice crystals. Meanwhile, other regions have experienced increases in tropical cyclones, the emergence of warm patches of ocean water or more intense heatwaves. These changes can only be explained when aerosol pollution trends are added to climate simulations. “I don’t think it was fully realised how much this [pollution removal] would affect the regional climate,” says Bjørn Samset at the Center for International Climate and Environmental Research in Norway.

Weather systems around the world are being warped further because of our efforts to curb air pollution

John Finney photography/Getty Images

Indeed, the scale and variety of these changes have prompted some researchers to describe the rapid removal of pollution aerosols as a “termination shock”. Yuan, for instance, describes the impacts of IMO shipping regulations as an “inadvertent geoengineering termination shock with global impact”.

“The intention for the fuel regulation was to limit the impact of these aerosols on human health, in coastal cities or general populations,” he says. “But when you reduce those [kinds] of pollution emissions, it has the same effect as reducing the number of aerosol particles in the air.” This is the opposite effect of proposed geoengineering strategies that inject aerosols into the stratosphere to reflect sunlight, so he describes it as a kind of “reverse geoengineering”.

Unsurprisingly, some of the biggest shifts have emerged in China. In 2022, mainland heatwaves in eastern China were up to 0.5°C more intense because of the country’s clean air improvements. But there are also strange “teleconnections”, a term used in climate science to refer to when a change in one part of the world triggers a climatic shift tens of thousands of miles away. The sudden emergence of severe ocean heatwaves, dubbed “warm blobs”, in the Pacific Ocean near Alaska over the past decade could be another result of China’s aerosol pollution reductions.

Researchers suggested in a paper last year that the reduction of pollution emissions in East Asia triggered coastal regions to warm, setting off a chain reaction of weather systems that led to a surge in water temperatures in the Pacific. Fish die-offs and toxic algal blooms are commonly found in these warm blobs. “The impact of anthropogenic aerosol forcing is more complex and far-reaching than we thought,” says Xiao-Tong Zheng at Ocean University of China in Qingdao, who co-authored the paper.

Coral bleaching

Damage to marine environments has also been caused by the reduction in sulphur aerosols from shipping. According to research that was published in June and is yet to be peer reviewed, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, already under pressure from climate change, has suffered further heating as a result of the shipping clean-up, putting its corals at greater risk of bleaching.

The effect has been so extreme that some researchers suggest the IMO should relax its pollution rules on the high seas to restore some of the cooling effect from sulphur. The idea is that in remote sea regions far from ports, the emissions from container ships are unlikely to have significant health impacts, so there is a greater need to consider ecosystem impacts like coral bleaching.

Ocean hotspots provoked by cleaning up ship emissions have put coral reefs at a greater risk of bleaching

Lillian Suwanrumpha/AFP

The findings suggest that aerosol pollution may be staving off some of the worst consequences of climate change elsewhere in the world. Samset points to the Indian monsoon, a vital summer downpour that supplies more than three-quarters of the country’s annual rainfall. Overall, the monsoon rain in India has intensified in recent years, a consequence of greenhouse gas emissions strengthening monsoon winds over the Indian Ocean, which drives heavier rainfall patterns on land that lead to devastating flooding. But the effect has been significantly dampened by high levels of air pollution in India and China, says Samset, as aerosols cool the atmosphere and weaken the forces that create rainfall.

That is an important factor for India to consider as the country plans for a changing climate. Although ongoing greenhouse gas emissions will continue to intensify the monsoon, the expectation is that India will soon follow the US, Europe and China in cutting air pollution as it transitions to cleaner energy sources. That would remove the dampening effect of aerosols, says Samset. “Suddenly, you [would] see a very strong intensification of the monsoon,” he says. “That’s really the driving motivation for understanding the regional aerosol changes. We can better anticipate and better plan for future changes.”

Without the Earth-cooling effects of air pollution, India’s monsoon rains may further intensify

CHANDU LUMBURU/AFP

While the most extreme changes are regional, the rapid abatement of aerosol pollution has also had a global impact on the pace of warming. Yuan’s 2024 research suggests the IMO shipping regulations could lead to a doubling (or more) of the warming rate of the global ocean in the 2020s compared with the rate since 1980. This would mean further record-breaking global temperatures could be in store this decade.

However, some researchers are wary of describing the planet’s response to cleaner air as a “termination shock”. James Haywood at the University of Exeter, UK, argues that a full-scale shock, resulting from the abrupt halting of a geoengineering scheme, would be far more severe. The term applies when temperatures jump so rapidly and by such a large margin that ecosystems cannot cope, he says. “The termination effect only really becomes an issue if the magnitude of the leap [in temperatures] is unprecedented globally and regionally,” he says.

The IMO shipping regulations, for example, have accelerated global warming by up to three years, says Haywood, meaning the margin of change isn’t dramatic enough to be a full-scale termination shock. “There wouldn’t really be a huge amount of problem with ecosystem adaptation to three years of global warming being released instantaneously,” he says. “What would be a problem is if you had 30 years of global warming being released in a very short time.”

Regardless of semantics, there may be important lessons here for understanding the potential risks and opportunities of any future, larger-scale geoengineering interventions. Research interest in solar geoengineering is increasing as scientists and entrepreneurs scramble for solutions to save some of the world’s most fragile ecosystems, such as coral reefs and polar sea ice. Researchers, including Samset and Zheng, say that deliberate interventions like these could one day be informed by data on how changes in aerosol emissions feed through into weather patterns – including how the emission location, time of year and type of aerosol particle all feed into these downstream effects. Yet if handled improperly, warns Zheng, “geoengineering could exacerbate climate change signals and extreme events in certain regions.”

It is a sentiment shared by Daniele Visioni at Cornell University in New York state. “To me, the biggest lesson is that there are no ‘risk-free’ decisions in our complex world. Geoengineering is not a magic wand and is not going to make our problems go away.”

Topics: