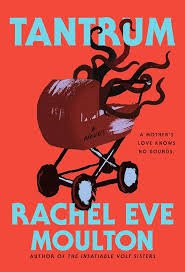

Sitting outside the entryway of the rustic Roots Farm Café in the small village of Tijeras, local horror author Rachel Eve Moulton readies herself to talk with SFR about her third novel, Tantrum (Penguin Random House, Aug. 2025), as her two daughters take turns petting the cafe’s resident cat.

Following her previous novels in the feminist horror niche, Tinfoil Butterfly and The Insatiable Volt Sisters, her latest book is the first to be set in New Mexico, specifically in the Sandia Mountains spanning the east side of Albuquerque.

The haunted house Tantrum takes its readers to is that of Thea, a mother of three who knew the second she saw her third child Lucia—her first daughter—that she was not human. Lucia is hungry, ravenous. She knows no bounds, and she’s much stronger and smarter than any three-month-old baby should be. Thea does not know what to do when Lucia’s hunger directs itself from raw meat to live chickens to her own brother. Thea cannot let anyone know about her daughter’s insatiability, not even her own husband.

Moulton’s punchy, yet cathartic venture through one day in the life of a mother trying to stop her daughter’s aberrant behavior from bubbling over—and a deep dive into Thea’s lifetime of being restrained herself—is a quick but impactful read. Her examination of motherhood, and what harm is purposefully or unconsciously passed down to daughters taught to keep the monster locked inside them, will draw any reader in, even through Thea’s initial hardened exterior and Lucia’s sharp teeth. This interview has been edited for clarity and concision.

My first question is the obvious one everyone goes for: What would you say first inspired you to write Tantrum?

When my first daughter was born, when I first met her. You go through pregnancy, and labor takes forever, and it’s uncomfortable—and then you’re introduced to this human being. And I had this reaction where I actually was holding her and screaming in her face, “It’s a baby. It’s a baby!” And that was the first moment I realized that I had thought I was carrying around some kind of alien monster. Like, deep down in my soul, I did not expect it to be human, but I didn’t know that about myself. So I was like, “Okay, what if I write a book where that feeling is there, but eventually it turns out to be true, and the thing born is actually a monster.” It was very voice-driven to that experience.

With this specific plot and its use of the monstrous child trope, it felt familiar to me. I grew up reading and watching stuff like Rosemary’s Baby, The Fifth Child, The Omen. Can you tell me about your sources of inspiration crafting Lucia as a character?

I love those things that you’re referencing, absolutely adore. There’s, of course, Night Bitch, which is a more recent book by Rachel Yoder. That is fantastic. Another one called Motherthing by Ainslie Hogarth—really stunning. Another one that’s not horror that I really like is Miranda July’s All Fours. I think right now, literature that is horror or horroresque that talks very plainly about experiences about being female in a more raw way that I can relate to—I’m very interested in that, and thinking about kids. Lucia’s a baby. I’ve got my own experience with my own kids, but also just really connect with working with young people. I think they’re the most interesting people in the room. Often, they’re the most genuine people in the room, so I gravitate towards that.

Is there anything that you would say that’s specifically different about writing a “monstrous child” who’s a girl as opposed to a boy?

I think that we’re all kind of monstrous. If we’re saying we’re not, we’re in denial. I think there was an interesting thing that happened for me when I found out I was having girls. When we found out that they were going to be girls, I did have this kind of misogynistic reaction that was like, “Oh crap, now I have to help them get through this and this and this and this”…assigned gender doesn’t even mean they’re going to be that gender. The whole thing is dumb, but you have these reactions that are, when they come to the surface, probably hugely challenging in a very helpful way. Thea has two boys, and Lucia’s there to challenge what we think about gender, challenge what we think about what it means to be good or bad, or female, or violent or not. It was really important to me that she was a girl for that reason.

The book also is very much centered around mother-daughter relationships—not only between Thea and Lucia, but also Thea and her own mother. What aspects of this relationship compel you most as a writer?

I am very interested in looking into how we pass down trauma—how we do it outright, and how we do it in subtle ways. What doesn’t get solved in the last generation gets passed down, and how do we stop that? What parts of that are we doing that we don’t even know we’re doing? I’m really interested in exploring that, and the best way I connect to it is through mother-daughter stuff.

I think with Thea, her instinct is to hide Lucia, because she has spent her whole life hiding those parts of herself—sometimes from herself, but definitely from others. When she sees it reflected on her daughter, she’s like, “We just need to handle this. I just need to clean it up,” because your child is an extension of yourself, and it gets confusing..

What do you hope that readers will take away from Tantrum as they finish it?

I hope that the book allows people to talk more openly about what it means to be a mother, to be a parent, to be ugly, to be violent, to be whatever it is that’s really going on under the surface. Stop being as reserved or polite and just, say the thing. I hope it encourages people to be more honest about who they are, even if they’re nothing like Thea or Lucia.

I wanted Tantrum not to go the way one might expect, which maybe is more like The Omen or something like that. Without giving anything away…I’m very interested in things that aren’t one thing or the other. Lucia’s a monster, but I didn’t want that to be the only side to Lucia, just like I didn’t, in the end, want Thea only to be angry, only to be a victim, only to be a mom, so I wanted to end the book in a way that fostered empathy even in the most dire of circumstances.