On becoming first minister of Northern Ireland in 1998, David Trimble appointed a man named Graham Gudgin to be his economics adviser.

In an interview with Stephen Walker, the author of this cradle to grave biography of Trimble, Gudgin recalls joking that the only problem with being an economic adviser to David Trimble was that, firstly, he had no interest in economics.

And secondly, he didn’t take advice from anyone on anything. It is a telling anecdote about a man, whom Walker claims, changed the political landscape of Northern Ireland.

Former prime minister Tony Blair and former taoiseach Bertie Ahern signing the Good Friday Agreement, which was supported by David Trimble. File picture: RollingNews.ie

Former prime minister Tony Blair and former taoiseach Bertie Ahern signing the Good Friday Agreement, which was supported by David Trimble. File picture: RollingNews.ie

Throughout the sweep of Trimble’s life, Walker captures his brittleness and power, his cunning and naivety, his highs and lows, his glory and tribulations, his domineering arrogance and his crippling doubt as he moves slowly from the margins to the centre stage of Northern Irish politics, where he makes one of the most crucial decisions in all of Irish history; the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, or the Belfast Agreement as he always called it.

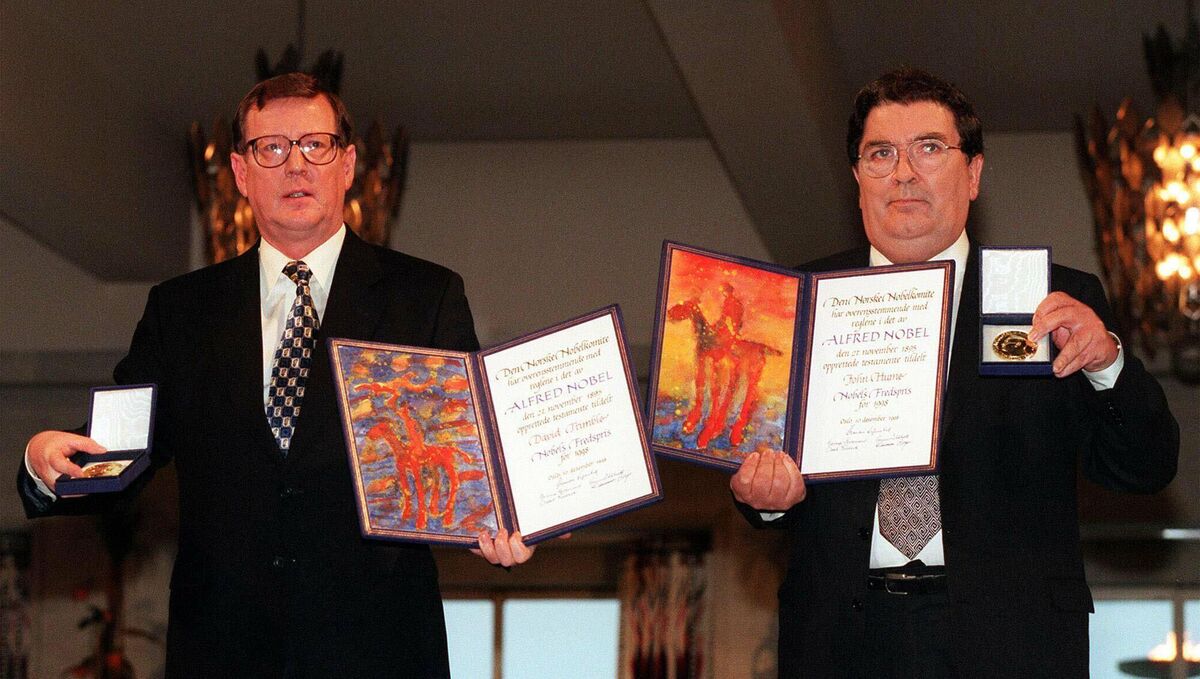

The 1998 Nobel Peace Prize laureates David Trimble and John Hume, displaying the diplomas and medals they received during the awarding ceremony in Oslo.

The 1998 Nobel Peace Prize laureates David Trimble and John Hume, displaying the diplomas and medals they received during the awarding ceremony in Oslo.

And that destiny was to deliver the enormous prize of peace to a Northern Ireland blighted by sectarianism, to which he contributed, since its foundation, and by violence for the three decades up to when Trimble made that fateful decision to do a deal with Sinn Féin, whom he loathed with every fibre of his being.

Walker’s Trimble is of the great man school of history but he is keenly attuned to how the structures of Northern Irish society produced men such as Trimble, John Hume, Gerry Adams, and Ian Paisely, three of whom played crucial roles in the Good Friday Agreement and one who although he loathed it, ultimately made it work when the Democratic Unionist Party entered power sharing with Sinn Féin close to a decade later.