For her birthday, assistant professor of radiology Gozde Durmus received an unusual present: the power to control cell levitation.

The gift, while exciting, wasn’t necessarily a surprise. Durmus and her lab have been working on using magnets to levitate cells for several years. But this year, the team added another tool to their repertoire.

By developing the Electro-LEV system, the lab made effective cell sorting possible through the use of electromagnetic fields, promising new ways to study and treat diseases like cancer and antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections.

“Just like magnetic levitation trains use electromagnets to lift and propel the train along a track, our Electro-LEV system uses electromagnets to control where cells levitate along the vertical axis,” said Durmus. “By adjusting the electric current, we can move cells up or down with precision, similar to how maglev trains adjust their magnetic fields to control speed and position.”

Durmus began to experiment with magnetic cellular levitation after working with nanoparticles and antibiotic‐resistant microorganisms. The observation that some bacteria would move farther than others in the presence of a magnetic field sparked her curiosity: would human cells behave the same way?

Durmus performed tests that confirmed her hypothesis — a cell’s density changes how it reacts to a magnetic field and how far it will travel in solution. The discovery will allow scientists to distinguish between types of cells and sort them accordingly.

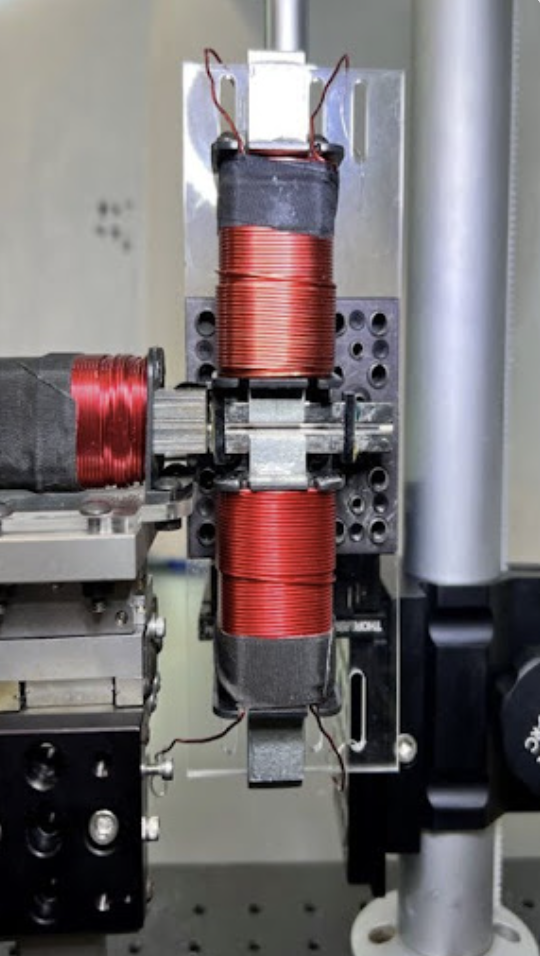

The system that enables the sorting process consists of a minuscule tube about one millimeter in diameter that runs between two permanent magnets surrounded by electromagnetic coils. The coils are novel elements that give the scientists the power to manipulate the cells. By controlling how much current is running through the coils at a given time, scientists can control the force of the electromagnetic field by exerting a repulsive force on the non-magnetic cells.

“You can manipulate the current injected into the coil,” said Victor Garcia, an electrical engineer who worked on the technical development of the system. “That way you can increase the magnetic field, and you can increase the force you’re applying to the particle and make it go higher or lower.”

For Suraj Pravagada, a postdoctoral research scientist in the Durmus lab, the Electro-LEV system represents a significant improvement from an earlier iteration developed in 2015 without electromagnets.

“[The electromagnetic system] transforms levitation from a passive observation tool into an active manipulation platform,” Pravagada said. “Separation stops being a waiting game and becomes a programmable protocol.”

Once the cells are levitated to different heights, Garcia explained, a syringe pump can suck the cells out of the other end of the tube and into different outlets. This way, lower density cells pass through higher outlets and higher density cells fall to the bottom.

Levitation is also gentle on the cells, which marks a triumph for a field that relies on sorting techniques that could damage samples, such as membrane-penetrating chemicals, high pressure environments and shearing forces.

“That gentle approach can turn a few precious cells into enough material for diagnosis, drug testing or culture in the lab, opening the door to personalized treatment,” said Sena Yaman, a postdoctoral researcher in the Durmus lab.

Precious cells, like the ones responsible for metastasis — the process by which cancer spreads between organs in the body — can be tricky to find. There is one circulating tumor cell (CTC) per every five billion red blood cells in the body. With the new levitation system, scientists can now pinpoint aggressive CTCs because they move at different speeds when levitated.

“In the future, this could be developed into a blood-based screening tool to monitor cancer patients for metastatic spread or even as a way to remove circulating tumor cells from blood before they establish new tumors elsewhere in the body,” said Durmus.