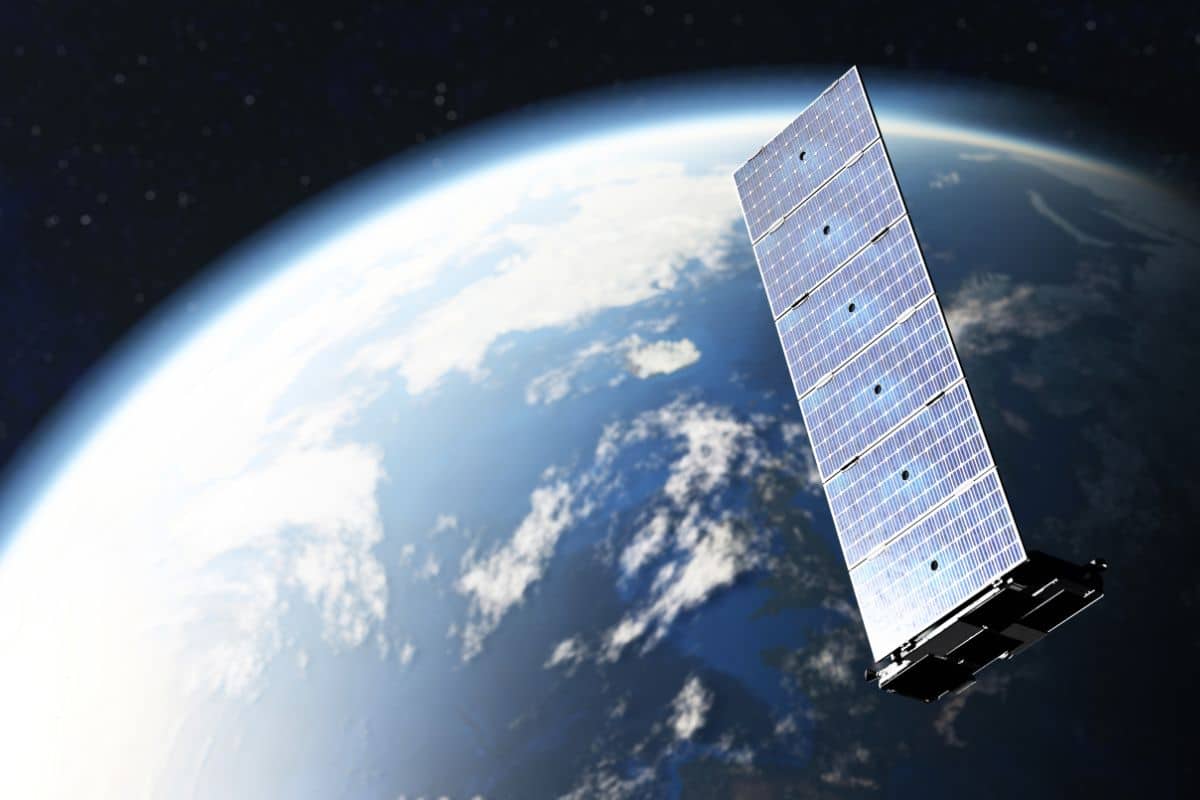

With more than 10,000 Starlink satellites now in orbit, SpaceX has cemented its dominance over low Earth orbit — and reignited growing concerns among scientists and astronomers about the consequences.

This past Sunday, the company launched two Falcon 9 rockets for the 131st and 132nd time this year, adding 56 more satellites to its ever-expanding constellation. In doing so, it crossed an extraordinary milestone: over 10,000 Starlink satellites launched since the program began.

SpaceX has now launched more than 10,000 Starlink satellites to date, enabling reliable high-speed internet for millions of people all around the world 🛰️🌎❤️ https://t.co/RDBIjiGcrK

— Starlink (@Starlink) October 19, 2025

Not all of them are still operational, however. Each Starlink satellite has a lifespan of about five years before being deorbited and burned up in Earth’s atmosphere. The first generation, launched in 2018, is already being retired. According to astronomer Jonathan McDowell, one of the world’s top experts in space object tracking, around 8,600 of these satellites remain active today.

That’s still an astonishing number. For comparison, in the first six decades of space exploration — from 1957 to 2017 — only about 8,000 satellites were launched in total. In just seven years, SpaceX has surpassed that figure by 2,000, single-handedly outpacing the rest of the world’s efforts combined.

Today, there are fewer than 12,000 active satellites orbiting Earth, meaning Starlink alone makes up more than two-thirds of them. And this is just the beginning: the company plans to expand its network to as many as 30,000 satellites.

A monopoly in orbit

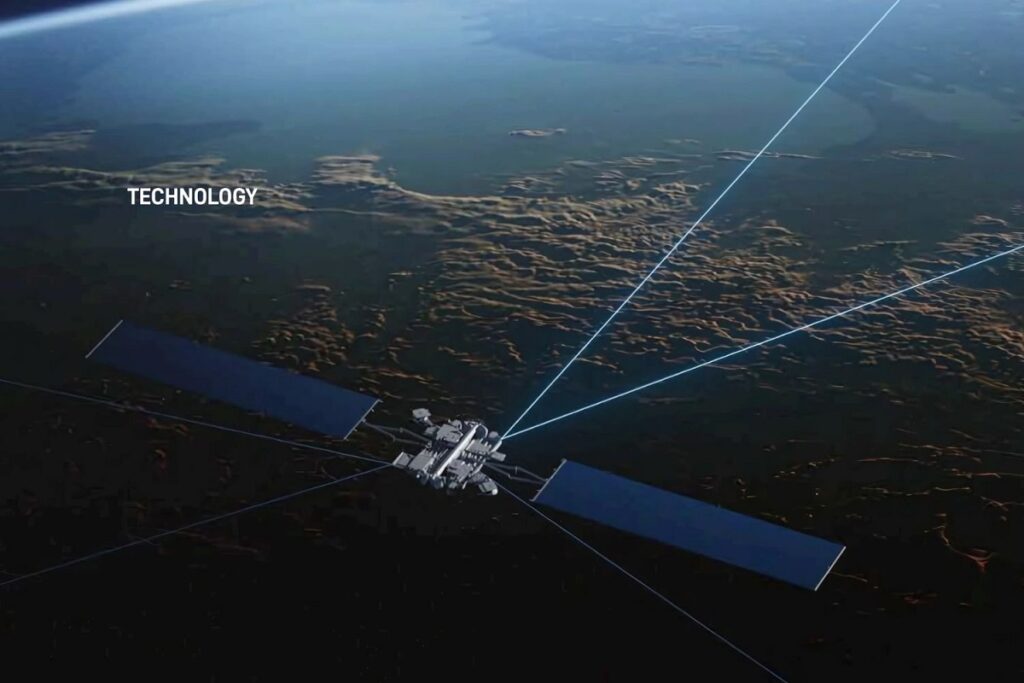

No one has come close to challenging SpaceX’s dominance. Eutelsat’s OneWeb — Europe’s leading internet satellite provider — has fewer than 650 satellites. Amazon’s much-hyped Kuiper project has barely passed the 150 mark.

© Space X

China may eventually pose the greatest challenge. President Xi Jinping’s administration is developing several megaconstellations — including Guowang, Qianfan/G60, and Honghu-3 — each expected to reach 10,000 satellites or more. But for now, these projects are years away, with only a handful of satellites launched. In the near term, no one is likely to dethrone SpaceX.

Trouble for the night sky

Astronomers were among the first to raise the alarm. The sheer volume of satellites has made it increasingly difficult for ground-based telescopes to capture clear images of deep space. Costly observatories — some worth hundreds of millions of dollars — are now struggling with Starlink streaks ruining their exposures. For researchers chasing rare or fleeting cosmic events, it’s a frustrating, sometimes heartbreaking, setback.

Environmental red flags

The concerns don’t end there. When thousands of Starlink satellites eventually burn up in the atmosphere, they’ll release vast amounts of aluminum and metallic oxides. These compounds can react with the ozone layer and alter chemical processes in the upper atmosphere.

Early studies show the effects could already be noticeable. Scientists suspect that satellite reentry is changing the chemical makeup of the mesosphere — a thin, high-altitude layer crucial to climate stability. The problem may seem minor now, but with tens of thousands more satellites planned, the impact could grow quickly and become significant.

And unlike pollution on Earth, this contamination can’t be cleaned up. Once these microscopic metal particles disperse, they can linger for years, their impact on the climate and atmospheric chemistry uncertain — but likely negative.

The collision crisis waiting to happen

There’s also the growing risk of collisions. As the number of satellites rises, so does the chance of impact — and each collision creates debris that can cause further collisions in a dangerous domino effect.

This is the feared Kessler syndrome, a cascading chain of impacts that could trap Earth in a cloud of debris and make space travel impossible for decades.

For now, SpaceX’s engineering achievement is undeniable. But it also underscores an urgent need for cooperation between governments, private companies, and researchers to create strong global regulations for orbital traffic. Without them, humanity’s race to dominate space could end up blocking the final frontier altogether.