When bacteria eat different kinds of food like sugars or more complex carbon compounds, they can send those nutrients down different “roads” inside a cell to make energy and build new materials.

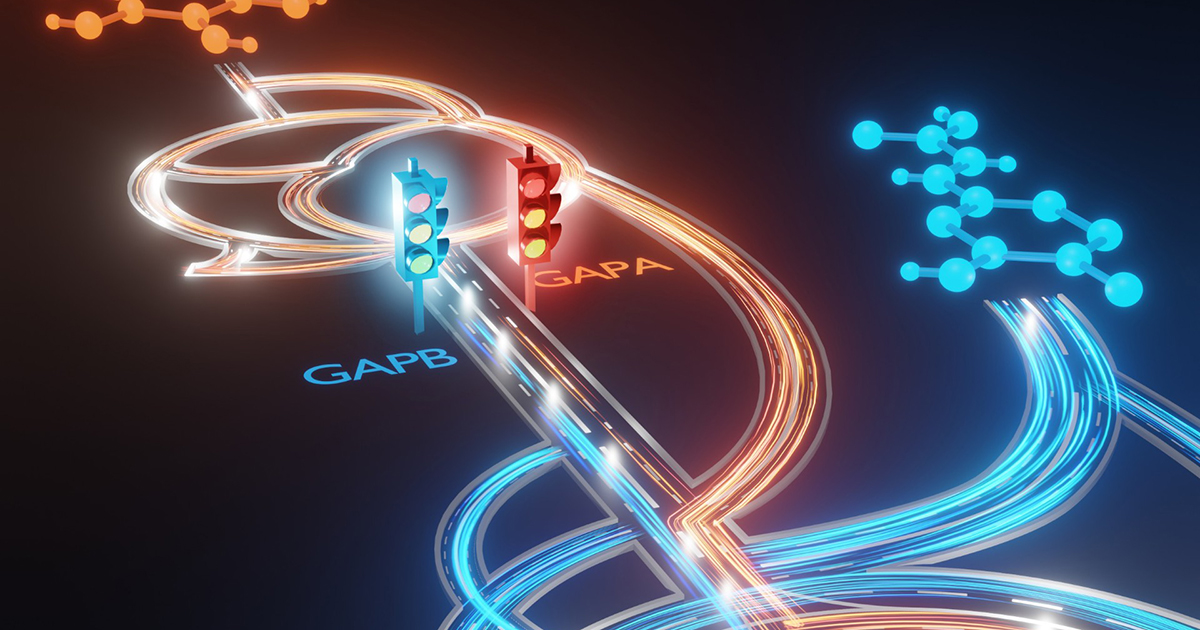

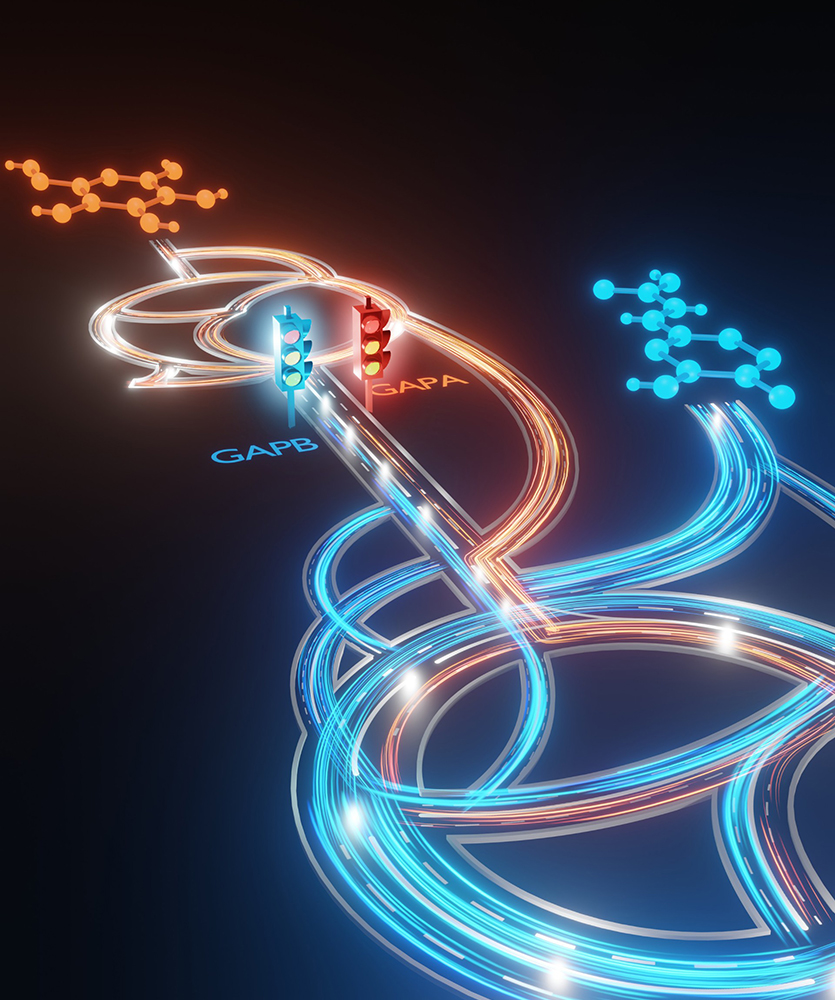

A new study from Northwestern Engineering’s Ludmilla Aristilde found that a single enzyme, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), acts like a traffic light that decides which road the carbon from different “foods” takes. By tracking how carbon atoms move through bacterial cells using special isotope labels attached to different types of food for the bacteria, her team showed that two versions of this enzyme send metabolism in opposite directions. By using these labeled carbon atoms, researchers can literally watch how the cell decides to metabolize food for energy and building blocks.

The finding helps explain how Pseudomonas bacteria, common in soil and known for consuming a wide range of carbon sources from plant waste to plastics, manage their internal “carbon traffic.” The insight could guide efforts to harness these bacteria for recycling waste or producing valuable materials more efficiently.

The discovery not only deepens understanding of bacterial metabolism but also points to practical applications in biotechnology, such as developing microbes that process carbons from different waste sources into useful chemicals or fuels.

“Understanding how the metabolism in Pseudomonas species operates is very important to engineer the traffic of carbon towards biotechnology targets such as the synthesis of valuable chemicals from complex wastes,” Aristilde said.

An expert in the dynamics of organics in environmental processes, Aristilde is a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the McCormick School of Engineering and a member of the Center for Synthetic Biology, International Institute for Nanotechnology, and Paula M. Trienens Institute for Sustainability and Energy. She presented her latest work in the paper “Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Homologs as Bifunctional Gatekeepers of Metabolic Segregation in Pseudomonas Putida,” publishing this week in the academic journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.