Much of what we know about animals in remote parts of the ocean comes from eavesdropping on them; quite literally. Underwater passive acoustic recording is vital for researchers to monitor and study marine animals. But a new, profoundly unsettling, study reveals that this tool isn’t as “passive” and “non-intrusive” as we thought.

Narwhals, one of the shyest and most sensitive whale species on Earth, keep slamming into it. At one site, it’s happening 10-11 times per day, and in some cases, it’s luring narwhals into a death trap. Researchers kept finding entangled and drowned narwhals in the lines of “harmless” scientific moorings. Now they know why.

“These results imply that oceanographic monitoring might alter the behavior of whales and poses a risk to their well-being, which should be investigated and accounted for in design. Our findings reveal the intrusive nature of a key scientific method, with implications for the management and conservation of vulnerable marine mammals,” the researchers write in the study.

No Easy Answers

Here’s what makes this so harrowing: Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM) is supposed to be the good-guy-tech of ecology.

For decades, if you wanted to study a whale, you had to chase it in a boat or tag it, usually with a dart. These methods are stressful for the animals and skew the data. PAM was the solution. The idea is simple: you drop a high-tech, battery-powered microphone (a hydrophone) on a mooring, anchor it to the seafloor, and leave.

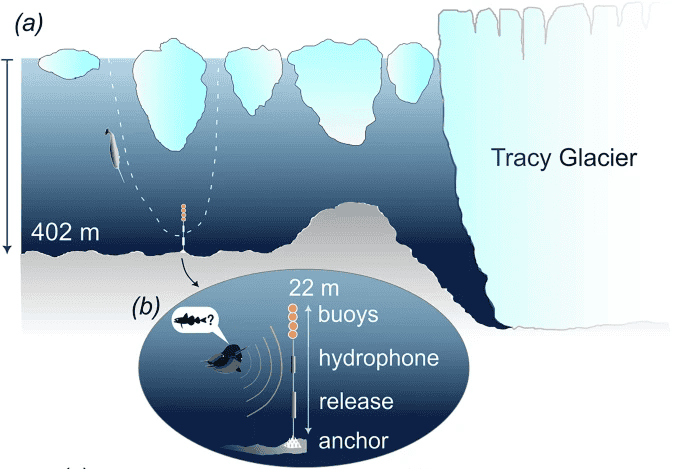

The mooring is a simple 72-foot-long setup. It has a heavy anchor on the bottom, a line, some buoys to keep it vertical, and the recorder itself, a titanium cylinder about the size of a large thermos. You install it and sail away, leaving the recorder to listen, undisturbed, for months. It’s considered the gold standard for understanding “undisturbed animal behavior”.

“Using passive acoustic monitoring to detect acoustically active animals helps to census biodiversity, understand animal behavior and habitat use, and reduce the negative impacts of human-made noise,” said Associate Professor Evgeny A. Podolskiy of the Arctic Research Center at Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan. “For these reasons, scientists increasingly rely on passive acoustic monitoring to answer fundamental ecological questions and manage conservation.”

But when a team of scientists led by Podolskiy retrieved three such devices, that’s not what they found.

Researchers placed the devices at depths ranging from 190 m to 400 m in the Inglefield Bredning Fjord in northwest Greenland, a critical summering ground for thousands of narwhals.

When they retrieved the recorders, the data was very loud.

The Disturbing Behaviour

These weren’t random noises. They had a terrifyingly precise signature.

First, the hydrophone would pick up the classic click… click… click of a narwhal’s echolocation. Then, the clicks would rapidly speed up into a “foraging buzz.” This is the whale’s terminal sonar beam as it moves in for a kill. The buzz would hit its peak, and then — BAM.

The sound of the impact would be so loud it maxed out the recorder, a powerful, low-frequency hit, often followed by a “broadband ‘rubbing’ sound”. This, the scientists believe, is the sound of a multi-ton whale scraping its skin and tusk against the metal mooring.

Altogether, there were 247 incidents of narwhal hits in more than 4,000 hours of audio records. These hits were detected on the two deepest recording devices located 25 km apart. However, the recordings were not continuous; they had ~15 min pauses, so the real number of incidents is likely even bigger.

“Our results suggest that narwhals repeatedly dived to visit the moorings out of playful curiosity or, more likely, due to confusion with potential prey,” Dr. Podolskiy said.

So, why are they doing it? The researchers landed on two possibilities: they’re playing, or they’re hunting.

Why the Narwhals Attack

Remarkably, the Inughuit hunters, one of the smallest indigenous populations in the world, had insights about this.

“Inughuit hunters were not surprised by the discovered interaction: they are familiar with narwhal entanglement in unattended gear. They also believe that narwhals like to play and are told so by their parents, and joked that narwhals might scratch their backs, like cats. While this is possible, and other arctic whales are known to rub their bodies over rocks, it is unlikely due to the high energetic costs of deep diving,” Dr. Podolskiy said.

The “foraging buzz” is perhaps the most telling example as it’s not a playful sound, but rather a weapon-lock. The narwhals appear to be in hunting mode before attacking.

There’s another clue that hints at hunting. Cod have a swim bladder, an internal, air-filled organ that controls their buoyancy. To a whale that “sees” with sound, that air bladder is the like a big bell that says “dinner.” It’s a huge acoustic reflector, bouncing back sonar pings like a bright, flashing light. To a narwhal, diving 1,000 feet deep in total darkness, the air-filled metal tubes dangling enticingly above the seafloor, must sound exactly like the biggest, fattest, juiciest cod in the fjord. So, they go in and attack the instruments.

A Conservation Nightmare

If the narwhals would just whack the gear and then move on, it would be one thing. But the researchers report that sections of two separate moorings were found floating at the surface of Inglefield Bredning. With them were the corpses of two narwhals. Local hunters who found them said both whales were tangled in the lines by their tails. One had been devoured down to the bone by amphipods.

The paper notes that since 2017, at least six passive oceanographic moorings have failed or been lost in this exact fjord. This was often blamed on icebergs but now, narwhals appear to be the most likely cause.

It seems that narwhals are actively engaging the scientific devices, and sometimes, getting killed in the process.

The implications are stunning. It would indicate that an important tool used in conservation could be doing some harm.

Narwhals are some of the most sensitive creatures in the ocean, so it’s not clear if this affects other creatures as well. But the researchers call for more investigation into this.

“Understanding animals’ interaction with industrial and scientific infrastructure can help reduce impacts on wild animals and improve our ability to implement and interpret autonomous field observations,” Podolskiy said.

As the Arctic melts and human activity increases, we need this science more than ever to protect these vulnerable animals. So, the authors are pleading for an urgent change. Mooring designs must be re-thought: no more loops, shorter lines, and, crucially, no more air-filled “prey-sized” sensors.

The study was published in Nature Communications Biology.