Study setting

This study was conducted at a tertiary care hospital, Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH), in Eldoret, Kenya. Kenya is a lower-middle-income country in Africa. The country is split into 47 counties inhabited by over 42 tribes. The population was estimated to be 54,027,887 people, according to the 2019 census [17, 18]. Approximately 24,428,416 are under 18 years old. Bungoma County, where the childhood cancer awareness campaign was implemented, is a county in Western Kenya that hosts a population of 1,786,973 people, of which approximately 800,000 are children below 18 years of age. The majority are Christians and belong to the Bukusu, a sub-tribe of the Luyha community. Approximately 87% live in rural areas, while 13% reside in urban areas. The primary sources of income are farming and business. The majority registers for primary school, and half of the schooling population enrols in secondary school [19,20,21].

Primary and secondary care facilities offer healthcare services. The National Ministry of Health supervises the Kenyan healthcare system [22]. Health insurance is offered through the Social Health Insurance System (SHIF), which offers coverage for childhood cancer care. A decentralized system is in place, providing increased authority for decision-making, resource allocation, and healthcare management to county authorities. The Kenyan healthcare system comprises six distinct levels of care. The first three levels encompass primary healthcare and include community health units (Level 1), dispensaries (Level 2), and health centers (Level 3). Community health volunteers are affiliated with community health units and conduct health promotion in their respective communities. Secondary care consists of subcounty hospitals (level 4) and county hospitals (level 5). Tertiary care is offered in national referral hospitals (level 6). Two level 6 hospitals, MTRH and Kenyatta National Hospital, offer comprehensive childhood cancer care in Kenya [23, 24]. Annually, around 140 children from Bungoma County would be expected to develop cancer based on the global incidence of 15 per 100.000 [25].

The awareness campaign

Between January and June 2023, a childhood cancer awareness campaign was implemented in Bungoma County. The campaign included training for all healthcare providers in Level 2 and 3 facilities, as well as their affiliated community health volunteers. The training focused on recognizing the six common and curable types of cancer, as defined by the GICC [6], treatment modalities, the importance of early detection, the importance of health insurance registration, and finally, how to refer children suspected of having cancer in a timely manner. The program focused on the GICC-prioritized common and curable cancers, as these represent the most frequently occurring cancers with high potential for successful treatment when detected early [6].

Following the live training session, a self-paced learning program was made available to healthcare workers via SMS learning [16]. This SMS-learning program delivered seven modules per SMS, on the same topics as the live training session. Upon completing both the live training session and the seven SMS learning modules, healthcare workers obtained a certificate.

Additionally, posters displaying early signs and symptoms of childhood cancer were distributed to all primary care facilities and posted in waiting rooms for both patients and healthcare providers to be reminded of the warning signs [26]. Phone numbers of the pediatric oncology team at MTRH were written on the posters for easy communication on referrals. Finally, a radio campaign was conducted to reach the communities of Bungoma County.

Study design

This was a mixed-methods study that used both a prospective and retrospective approach to evaluate the impact of the awareness campaign. The prospective approach included parental interviews with the parents of children from Bungoma County at MTRH who were newly diagnosed with cancer after the start of the implementation of the childhood cancer awareness campaign in Bungoma County. Parental interviews were conducted using a structured questionnaire developed by a panel of experts from Kenya, the United States, and the Netherlands in pediatric oncology, informed by a review of the literature on delays in access to childhood cancer care [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. (Supplementary file 1). Additionally, retrospective data were obtained from the hospital registry at MTRH to compare the number of referrals of children with cancer before and after the start of the awareness campaign.

Parental interviews

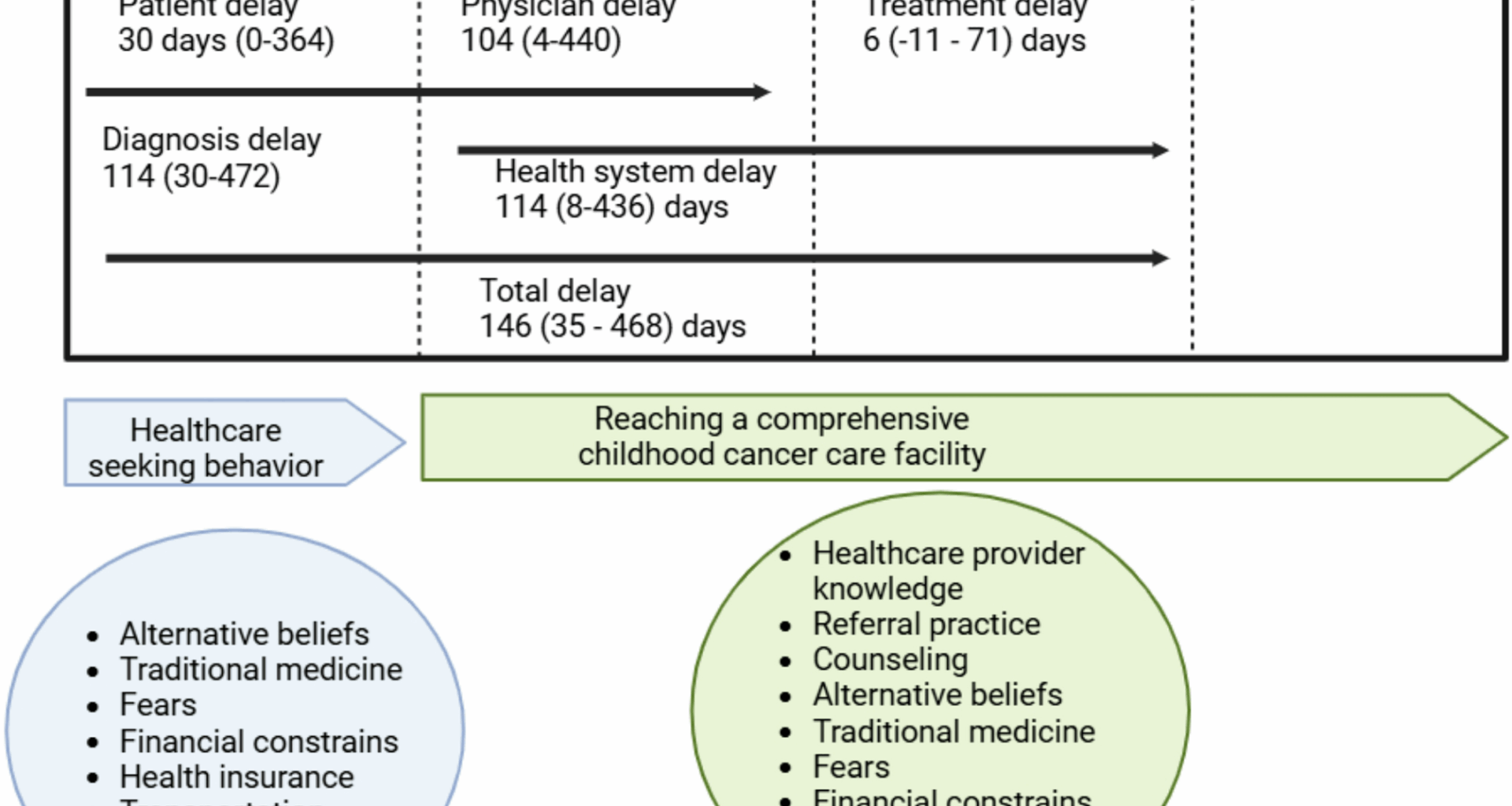

All children up to 14 years of age, referred from Bungoma County, confirmed to have childhood cancer, were eligible for inclusion starting from January 2023 up until December 2024. The research nurse monitored all referrals arriving from Bungoma County at MTRH and proceeded to an informed consent procedure prior to the parental interview. The interview was conducted in Kiswahili and consisted of a structured questionnaire that collected the following data: socio-demographic information, clinical details, delays, usage, and perceptions of both conventional medicine and TCAM, as well as barriers to referral. Regarding delays, we identified six distinct types: patient delay, physician delay, diagnosis delay, treatment delay, health system delay, and total delay [34]. Clinical data included sex, age, type of cancer, stage of cancer, and early death. Early death was defined as death within 42 days after diagnosis [35]. Stage of cancer was defined as low in solid tumors, stage 1 or 2, and as high in stage 3 and higher. Socio-demographic variables, including parental age, ethnicity, religion, occupation, and income, were collected to assess the representativeness of the referred patients in relation to the broader population of Bungoma County. Regarding the different types of delays, several questions were included to identify the causes of each type of delay. For patient delay: onset of symptoms, action upon onset of symptoms, usage of conventional medicine and TCAM, transportation challenges, health insurance status, beliefs about cancer. For physician delay: treatment for other illnesses, counselling on cancer, appropriate referral, counselling on SHIF. For diagnosis delay: action upon first presentation at MTRH. For treatment delay: the time from diagnosis to the start of treatment.

Comparison of referrals before and after the awareness program

Data on annual referrals of newly diagnosed children with cancer from Bungoma County to MTRH were extracted from the institutional registry for the period from 2014 to 2024. As the registry was established in 2014, this year marked the starting point for the pre-intervention period, which extended until December 2022. The post-intervention period was defined as January 2023, corresponding with the launch of the awareness program, through December 2024.

Statistical analysis

Data collection was done using Castor version 0.1.45. All data was anonymized using patient identifiers. Data management and analysis were conducted using SPSS version 26.0. Frequency distributions, medians, means, and standard deviations were calculated from the dataset to describe the data obtained from parental interviews on the characteristics of newly referred children with cancer. We compared the proportion of children with cancer referrals originating from the intervention province before and after the implementation of the intervention. The pre-intervention period was defined as 2014–2022, and the post-intervention period as 2023–2024. For each period, we calculated the proportion of referrals from the intervention province relative to the total number of referrals from all provinces combined.

To assess whether the observed change in proportions differed significantly between the two periods, we constructed a 2 × 2 contingency table (province of referral: intervention province vs. all other provinces; time period: pre-intervention vs. post-intervention). We then applied a Pearson chi-square test to compare the distribution of referrals across periods. When cell counts were < 5, Fisher’s exact test was used instead.

All analyses were two-sided, and statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics and Research Committee (IREC) at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH) with reference number IREC/2021/216 and approval number 0004060.