Surprisingly, raccoons can get even cuter. Image credits: Gary Bendig.

Surprisingly, raccoons can get even cuter. Image credits: Gary Bendig.

Our cities are chaotic, noisy, and dangerous. To many of us, they feel like home. But to most wild animals, they’re a hellscape. Some animals have found ways not only to survive, but thrive in the concrete jungle.

A fascinating new study out of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock suggests that North American raccoons (Procyon lotor) are undergoing a physical transformation directly linked to their life in the city. Specifically, their faces are changing.

Urban raccoons are developing significantly shorter snouts than their rural cousins. This suggests that raccoons are entering the early stages of “domestication syndrome.” This is the same biological process that turned wolves into pugs and wild boars into farm pigs.

The City Mouse and the Country Mouse

You’d assume domestication involves some kind of selective breeding. This isn’t the case here. We’re not putting raccoons in pens, but by building cities and filling them with calorie-dense refuse, we have created a massive, unintentional evolutionary experiment. The raccoons are domesticating themselves.

In fact, most biologists today believe that the first step of domestication starts with natural selection. Voluntary or not, humans create a niche. In this case, the abundance of food scraps you can find around trash in cities, and the lack of large predators. This creates an incentive for animals to exploit this niche. But they need to tick one additional box: they need to be chill.

An animal with a strong “fight or flight” response burns too many calories running away from slamming doors or passing cars. They don’t have good odds in the city. For the country mouse, a sudden noise usually signals danger. The city mouse usually adapts dampened responses to such stimuli. They are the ones bold enough to raid a dumpster but calm enough not to bolt when a human walks by.

But this is where things get a bit strange, with something called the “Neural Crest Domestication Syndrome” (NCDS) hypothesis.

The adrenal glands, which control fear and excitement, are formed in an embryo by a specific group of stem cells called neural crest cells. If nature selects for animals with less adrenaline (tameness), it is essentially selecting for embryos with fewer or less active neural crest cells.

But neural crest cells are multitaskers. They also build the cartilage and bone of the face, the pigment in the skin, and the cartilage in the ears. In other words, the “domestication package” comes with floppy ears and a shorter, more juvenile-looking snout. To us humans, this signals a less dangerous animal, and we tend to perceive it as cuter.

The Urban Laboratory

The story starts with trash, says Raffaela Lesch, an assistant professor of biology at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

“Trash is really the kickstarter,” she said. “Wherever humans go, there is trash. Animals love our trash. It’s an easy source of food. All they have to do is endure our presence, not be aggressive, and then they can feast on anything we throw away. It would be fitting and funny if our next domesticated species was raccoons. I feel like it would be funny if we called the domesticated version of the raccoon the trash panda.”

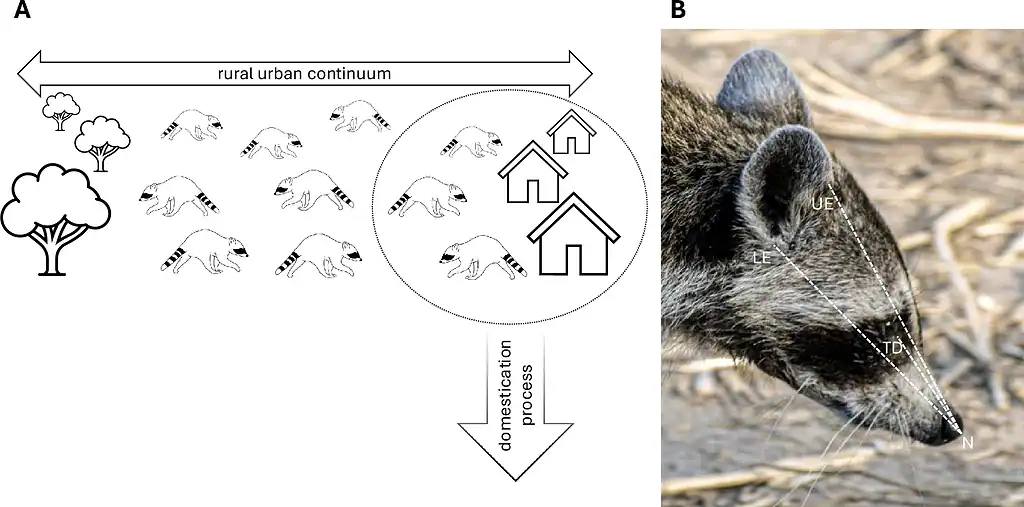

Out of all the changing traits, the snout is the easiest to observe. Lesch, who recruited over a dozen undergrads and graduates for the study, focused on this.

Measuring raccoon cuteness for science. Image from the study.

Measuring raccoon cuteness for science. Image from the study.

The research team utilized a massive repository of citizen science data: iNaturalist. They pulled nearly 20,000 images of raccoons uploaded by everyday people across the continental United States. After a rigorous filtering process to ensure they were looking at the correct angles and living animals, they analyzed the skull geometry of raccoons from deep rural woodlands to dense metropolitan centers.

They measured the “snout-to-skull ratio.” Because they couldn’t measure the actual size of the raccoons in the photos (a photo doesn’t tell you if a raccoon is ten pounds or twenty), they looked at proportions. They measured from the tip of the nose to the eye, and compared it to the rest of the head.

Urban raccoons possess significantly shorter snouts compared to rural populations. Specifically, the study observed a 3.56% reduction in snout length in the city dwellers. That number might sound small, but in the slow grind of evolution, a nearly 4% morphological shift across a population is massive.

This mirrors what we have seen in other species. Urban red foxes in London, for example, have developed shorter snouts than their country counterparts. Wild house mice in Switzerland have shown similar changes in head shape alongside white fur patches the longer they live in barns near humans.

A Curveball from Climate?

Of course, things are rarely simple and straightforward in evolution, and there’s a hidden variable here: climate.

Cities are urban islands, which means they’re several degrees hotter than their natural surroundings. There is a biological principle called Bergmann’s Rule, which generally posits that animals in colder climates tend to be larger and have different proportions to retain heat. The researchers found that climate does impact snout length. Raccoons in warmer climates generally have shorter snouts than those in the freezing north.

However, even after statistically controlling for climate zones, the urban effect remained rock solid. An urban raccoon in a cold climate has a shorter snout than a rural raccoon in that same cold climate. The city exerts a pressure that is independent of temperature. It is a pressure born of proximity to us.

What makes this study even more remarkable is that it was done as part of a class.

“The idea behind biometry, where students learn how to code and use statistics, is a class that is difficult to teach,” Lesch said. “I wanted to teach this class in a way that students would have their own data that they collect and analyze. The benefit is that I didn’t have to push students to complete the work. They were intrinsically motivated because they cared.”

This doesn’t mean you should try to pet the next raccoon you see. They are still wild animals, and vector species for diseases. But they are less wild than they were a hundred years ago. They are crossing the invisible threshold from “wildlife” to “commensal” — organisms that share our table, or at least, the crumbs that fall from it.

The study was published in Frontiers in Zoology.