To read Part I of “Fred Lonidier’s casual photography,” published by e-flux Education in December 2024, visit here.

Fred Lonidier’s casual photographs of the San Diego Group artists from the mid-1970s chronicle these artists’ entries into new working conditions, and the attitudes they brought to their performances within them. In these years, Lonidier and his peers went from students to teachers and mentors at the University of California, San Diego. After graduating in 1972, Lonidier was inducted into the faculty as a photography professor. Martha Rosler and Allan Sekula taught as graduate lecturers until completing their MFAs in 1974, returning to campus as lecturers and collaborators throughout the rest of the decade.

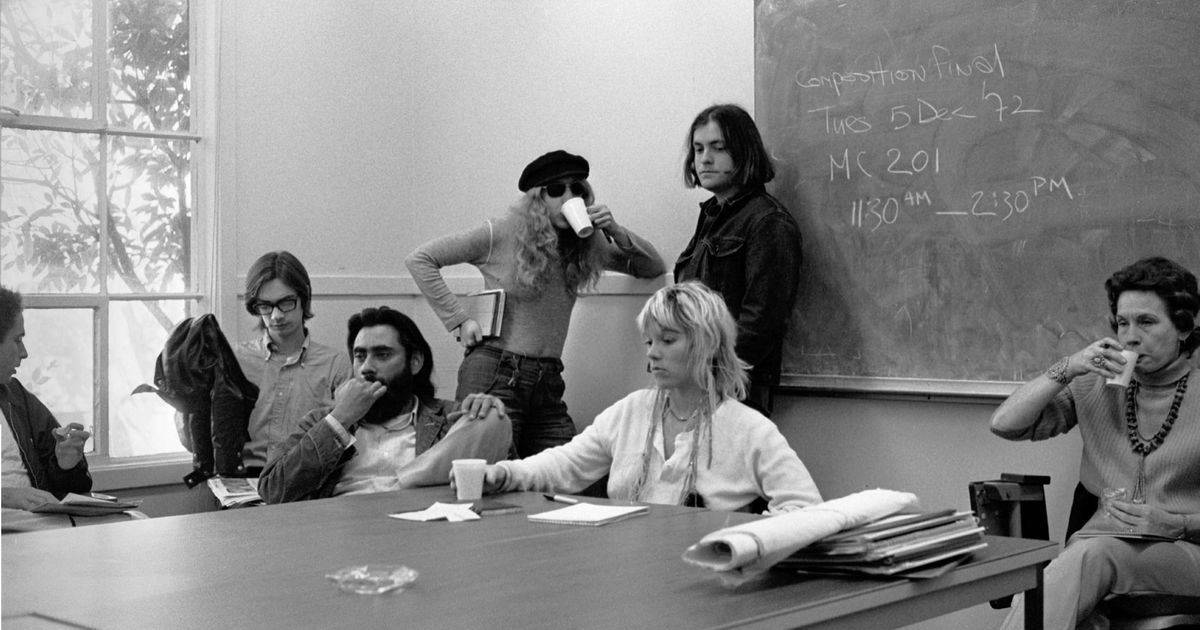

In a series of exposures by Lonidier from 1972 labeled “department meeting,” we see his recurring characters gathered around the far end of a classroom table. Sekula leans against the chalkboard, looking downwards, eyes half shut. Rosler, sporting dark sunglasses and a cabbie hat, raises a coffee cup to her lips, shielding even more of her face. San Diego Reader film critic Duncan Shepherd fixes his gaze on the newspaper in his lap, holding a jacket aloft on his hand. While this photograph appears candid, the artists’ boredom acts as a mask before Lonidier’s camera. It is as if they have conspired with Lonidier to portray themselves at a distance from their institutional roles. These young artists and teachers were no doubt conscious of the visage as a political medium, which Letter to Jane, Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin’s dissection of a single photograph of Jane Fonda in Hanoi, aptly articulated that same year. Like actors in the films of Godard’s Maoist period, the subjects in Lonidier’s photograph nod, if not wink, as they are transformed into familiar images, though their manner conveys solidarity rather than ironic inversion. This was not La Chinoise (1967).

The workers at UCSD, doing their jobs in front of Lonidier’s lens, direct our awareness to spaces beyond alienated roles. Amid depictions of institutional labor—students installing a poster for a university art exhibition, a councilor answering the phone in her cubicle—Lonidier captures sidelong gazes and offhand gestures. These signals point to the scope of life that resists being reduced to the fulfillment of a task, the mere image of a worker. Lonidier’s camera also captures the finer textures of class and social affiliations. At a reception for Robert Irwin’s sculpture Two Running Violet V Forms, which was added to the university’s Stuart Collection and permanently installed in its eucalyptus groves in 1983, Lonidier captures elder patrons being served champagne in plastic catering cups by a bow-tied waiter. In another of his photographs of a modest university opening, parents and administrative workers commingle with students as they take in the art on view, interacting casually around modest spreads of potlatch offerings and cheap wine. The public institution functions as a temporary habitus for a diverse student body and their families.

Lonidier’s casual observations recall the subtle depiction of class within several seminal works by the San Diego Group, such as Sekula’s Aerospace Folktales (1973), a series of 142 photographs accompanied by text that spun a narrative around daily life in his family home during a period when his father, an aerospace engineer, had recently been laid off from Lockheed Martin. In several photographs from that series, Sekula, pointing his camera at his father’s book collection, finds a clue to the origins of his vocation as an artist within his father’s modest cultural aspirations. Like Aerospace Folktales, Lonidier’s photos portray the class context of UCSD not as an assembly of fixed identities but as the scene of many converging stories shaped by opportunities never equal.

Lonidier figured the San Diego Group Artists within this arena. In his photographs from this period, we see a young Rosler at an opening for a graduate student’s exhibition, posing for the camera with a man in front of wall-mounted photographs of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970). We also see Phel Steinmetz performing his duties as a photo technician, perched on a ladder while documenting an Eleanor Antin performance. Years later, Lonidier also captured Steinmetz teaching Sekula to use a 4×5 camera. In their early work, the San Diego Group artists were each independently drawing connections between their personal biographies and historical class narratives. Lonidier pictures the environment that served as the backdrop—and inspiration—for this praxis. He photographs the cohort as young adults, engrossed in their respective relationships and private concerns while also developing a heightened awareness of their socioeconomic surrounds at the dawn of a nationwide recession, the culmination of the Civil Rights movement, and the emergence of feminism’s second wave.

During the mid-seventies, Rosler, Sekula, and Lonidier employed theatrical modes in their work, still using the UCSD’s Visual Arts Department as their stage. Take for instance Rosler’s video Vital Statistics of a Citizen, Simply Obtained (1977), in which a medical technician, played by Steinmetz, transcribes the physical measurements of a female patient, played by Rosler. In a second-person voiceover narration, Rosler synthesizes passages from American housekeeping magazines and nineteenth-century medical accounts, and constructs a broad historical arc of sexual violence and medical objectification. At the same time, the presence of her own voice and body in the video grounds her analysis in a particular place and time.

A decade later, Sekula would identify this piece as an example of the group’s original proto-documentary strategies, calling it “an allegorical feminist attack on the normalizing legacy of Quetelet and Galton,” the nineteenth-century pioneers of normative criminology and eugenics. Yet Rosler’s video also enacts a documentary function, as a record of roleplay enacted on a makeshift set inside a university classroom. It is worth noting that Rosler, playing the woman, cast a male colleague known for his technical proficiency in photography—to play the examining doctor. Rosler generates another level of meaning by mirroring a classically gendered imbalance of power in her actual life. In turn, her video changes our perception of Lonidier’s archive. It alerts us that the milieu he was photographing trafficked within a culture of performance, and that its participants acted out power dynamics and mimed what institutional roles expected of them.

Another projection of male authority: Lonidier’s 1973 photo of David Antin, then the UCSD Visual Arts Department chair, taking a phone call in his office. Antin, answering the call while standing in front of a poster of one of Lichtenstein’s “POW!” punches, displays a look of dissatisfaction with the person on the other line. He directs an open palm towards the camera, presenting himself with an intensified legibility for Lonidier’s camera. Standing before the Lichtenstein poster, his pose seems to caricature the aesthetic tyranny of an art school dean over an art school. As in many of Lonidier’s photographs of his colleagues, the person in front of his camera seems to be engaging with Lonidier in a subtle game of recognition.

Sekula employs a similar sensibility in his seminal photo essay School Is a Factory (1978–80), which portrays scenes of institutional inequality drawn from his experience teaching at Costa Mesa’s vocational school and UCSD’s art department. The photographs that Sekula took to illustrate that project, of a kind with Lonidier’s, blur the line between being candid and staged. The images show a business administration student practicing using a milling machine and photography students examining the waist-level viewfinder on a medium format camera. Unlike the strictly factual details that accompany Lonidier’s exposures, the extensive captions Sekula provides for his images impose a polemical significance. One caption tells us that a photograph of faculty member and Fluxus performance artist Alan Kaprow sitting at a table with the sculptor Ana Mendieta is of a Chicana woman being denied a teaching position, her interview alone fulfilling the school’s diversity requirement. School is a Factory does not treat images as authentic evidence; instead, Sekula presents his narratives through an overt superimposition of meaning overdetermined by well-known structural forces. Captured, according to the caption, in a Hilton hotel room, the mystery as to whether this photograph is a recreation in collaboration with Kaprow or an instance of sly reportage documenting an act of discrimination is central to the piece’s Brechtian form.

In contrast to School is a Factory and other San Diego Group artworks from the period, in which narratives are applied to images, Lonidier’s casual photographs—which are not artworks, per se—leave us with something more akin to a conventional archive, with images accompanied only by informational details. In one image, taken in 1983, the infamous European filmmaker Jean-Pierre Gorin stands among a crowd of students outside Mandeville Center’s Annex Gallery, mingling around jugs of wine at the opening of an exhibition. A woman graduate student stands besides Gorin, glancing toward him as she giggles and adjusts her hair. The photograph shares the easy legibility of the images within School is a Factory. Something could no doubt be made of this scene of intermingling. Has Lonidier caught Gorin “flirting?” The image is captured as if to anticipate a polemical use. But without any gesture from Lonidier to frame it politically, these various associative interpretations remain at the level of latent projections. The image becomes a model of documentary material in its ur-state, prior to being put to use.

Lonidier’s photographs expand the critical model of the San Diego Group by subjecting its activities within the university to the effects of documentary around which they aimed to author their critiques. A 1978 photograph by Lonidier teaches us “Four Lessons in Photography for the Petit-Bourgeoisie,” showing a chalk-drawn diagram by Sekula scrawled on the concrete exterior of the Mandeville Center. The diagram depicts cartoon field cameras set atop scales of judgment that teach the moral weight of angle: look down at the slums in “pity”; look up at the police in “fear.” When student graffiti was cleaned by the janitorial staff, the diagram was left up. “I have the theory,” Lonidier has said, “that they thought, ‘well, this must be for the photography department,’ because there were two entrances nearby to the photo classroom!”!”

A correct assumption, as Lonidier recalls. “I thought this was a succinct description of what we’re about. You have to really address yourself to the functions of education, from preschool to the PhD in the United States, and the critiques of them. From the Vietnam War to this day, people have been asking, ‘who’s this education for? Who does it serve, anyway?’” Contextualized within Lonidier’s archival series, the question asked by Sekula’s diagram gets directed toward Lonidier’s photograph of it and the rest of the photographs with which it is collected. Which angle does Lonidier’s camera occupy, and what message does that angle convey? What interests do these photographs serve?

By the 1980s, a critical discourse on photography would begin to reproduce itself in American universities. Sekula and Rosler’s writings were in the curricula and anthologized in textbooks such as Richard Bolton’s The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography (MIT Press, 1989). Operating outside of any feasible commercial career trajectory, all three artists relied on universities as their primary economic support system. Sekula took a permanent position in the photography program at California Institute of the Arts in 1985 and remained at the school until the final year of his life, and Rosler taught at Rutgers from 1980 to 2010. The critical realist lens that Lonidier cast on his everyday surroundings at the university was praxis, assessing the material circumstances and power dynamics among students, professors, and faculty within the university.

In a series of photographs Lonidier took in his classrooms, students line up behind desks, passing around a scroll of prints and circumambulating around the room to view images mounted on the walls. A spread of zines and printed ephemera is laid out on a table for perusal. Like his photographs of Sekula’s chalk drawing, these pictures of Lonidier’s class aid the critical frameworks they depict. Lonidier’s straight-on perspective does not elevate his own classes as examples of heroic virtue. It subjects them to a model of scrutiny, exposing them to the specific vulnerabilities that are revealed under archival conditions. The activity in the classroom is both the locus of critical scrutiny and the object of critical attention. By refraining from heavy self-censorship in his casual photography, Lonidier resisted the simplistic rigidification of critical distance as a sign of “good” documentary strategy.

In her 1981 essay “In, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography),” republished in 1989 as the concluding essay in Bolton’s The Contest of Meaning, Rosler refers to a disagreement with her friend, “a good, principled photographer who works for an occupational health-and-safety group.” The two were discussing Dorothea Lange’s famous photograph Migrant Mother (1936), which had become the subject of controversy after its subject, Florence Owens Thompson, went on record to bemoan her lack of remuneration. The “good, principled photographer,” who, based on Rosler’s reference to his work The Health and Safety Game (1976/78), we know to be Fred Lonidier, argued that the photograph “stands over and apart from [Thompson], is not-her, has an independent life history.” For Rosler, this abstraction from the instance erodes the basis of historical specificity in which the political stakes of documentary inhere. Rosler argues that this “covert appreciation of images is dangerous insofar as it accepts not a dialectical relation between political and formal meaning, not their interpenetration, but a hazier, more reified relation.” Lange’s photograph, per Rosler’s argument, carried with it the possibility for an ahistorical interpretation as one of its liabilities.

Rosler wrote this essay in the context of praxis, discussing her own The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems (1974–75), a text-image work in which she printed photographs of the Lower East Side street with bottles and other traces of its occupants and paired them with pages typewritten with synonyms for drunkenness. Both Lonidier and Rosler were certainly working conceptually; Lonidier, as Rosler alludes, had recently completed The Health and Safety Game, his cybernetic information display taking score of laborers’ workplace injuries and their battles with corporate bureaucracy for healthcare and compensation. Were they not both taking photographs? Rosler’s casting of Lonidier as her interlocutor seems motivated in no small part by his everyday role as a photographer, in so far as his picture-taking resembled documentary practice. It is not such a stretch of fiction to see Lonidier as someone for whom the liabilities of classical documentary were worth the gamble of interpretation out of context.

Lonidier courts the contradictions of Lange’s famous image in his photograph labeled “Graduate students with baby,” which depicts a young family sitting on a large concrete planter encasing a birch tree. The father holds the baby, while the mother sits apart. The picture documents a singular context and moment in time, taken within specific artistic, economic, and personal relations. The graduate students-cum-parents are political video artists Ernest Larsen and Sherry Millner, codirectors of the videographic satire on the nuclear family Out of the Mouths of Babes (1986). As a casual photograph, for certain eyes, it is them. Still, the image seems to lend itself to use beyond a biographical contribution to the career legacies of the artists—in this regard, it does not promise to remunerate its sitters—and even beyond the local place or time it was captured. In the vein of Migrant Mother, “Graduate students with baby,” can be generalized from this instance. It can be made to stand for family relations in a progressive university art department that served a locus of feminist organizing and political self-definition amid the conservatism of the 1980s. And, in a further degree of generalization, it can stand for a wider field of shifting cultural attitudes as a portrayal of the distribution of domestic labor in a period of shifting awareness and struggle. Lonidier’s labeling, emphasizing this function, signals the way in which the archive of his casual photographs allows us to see the world of contemporary art education through typological categories.

Lonidier applied these tags to the photographs he took casually at UCSD as a retroactive framing of their archival significance. The boundary between critical and sentimental memory is blurred, as it is for many artists. This reframing of the casual as the archival resembles Lonidier’s gesture in 29 Arrests (1972) previously discussed in the first part of this essay, but also his work Two Girlfriends (1973), for which he reframed photographs that he took as a teenager of two former girlfriends. Lonidier’s offering of his own casual photographs as a public record estranges them from their original “personal” function. This act of reframing generates an opening in the San Diego Group’s conscious political project to the unconscious forces of photography; a pre-theoretical model in which the conditions of the documentary archive contaminate, trouble, and progress authorship by registering subjective expression within the frame. As a mirror image of the San Diego Group project, Lonidier’s casual photographs focus our attention on the transformation of image-consciousness into political determination. In so doing, they anticipate the San Diego Group’s immanent work with the dialectic volatility of the journalistic image.

This essay has been excerpted from Nilo Goldfarb’s forthcoming book Fred Lonidier’s Casual Photography, which will be published by Nauener Platz in 2026.