Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

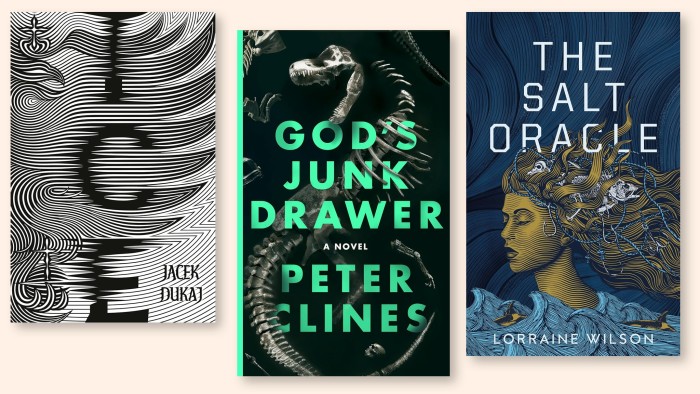

Should anyone have a hankering for some postmodern speculative fiction that deals with weighty topics such as philosophy, imperialism and quantum physics, then they need look no further. Ice by Jacek Dukaj, translated by Ursula Phillips (Head of Zeus £25) has all that and more in its 1,100-plus densely typeset pages.

The Polish author’s sixth novel, originally published in his native country in 2007 and recipient of several awards, is set in an alternate 1920s Russia caught in the grip of an everlasting winter. The cause is the Gleissen: ineffable angelic entities who emerged after the Tunguska asteroid impact of 1908. Their freezing influence has spread across the land, and in its wake come new, strangely transmuted materials — a superstrong form of iron, for instance, and a kind of coal that absorbs rather than releases energy when burned. This, in turn, has given rise to valuable new technologies, sparking an industrial revolution instead of the Bolshevik one of our own timeline.

Young Polish mathematician Benedykt Gieroslawski is dispatched from Warsaw to Irkutsk aboard the Trans-Siberian Express to find his exiled father, who the authorities believe can communicate with the Gleissen. Benedykt’s journey brings him into contact with all manner of rival political factions and sees him encounter real-life historical figures such as Tesla and Rasputin.

It would be trite, but not inaccurate, to say that Ice moves at a glacial pace, with pages-long paragraphs and much sombre musing by the protagonist. Ursula Phillips has braved the monumental task of translating Dukaj’s tome into English, and the result is a very readable but at times dauntingly abstruse work. It’s one of those novels for which the adjective “ambitious” is both praise and condemnation.

Somewhat lighter fare is on offer from Peter Clines with God’s Junk Drawer (Blackstone £24/$29.99). This is a nice riff on The Lost World — Conan Doyle, not Crichton — in which young Billy Gather, back in the 1980s, disappears along with his father and sister through a wormhole into a prehistoric valley where dinosaurs roam and time moves differently. Five years later, he reappears, alone, his father dead, and for a while attains unwanted celebrity status.

Fast forward four decades, and Billy is now an academic going by the name Noah Barnes. Accompanied by a handful of students, he re-enters the valley, hoping to retrieve his sister. The place isn’t inhabited only by dinosaurs; there are aliens, robots, Neanderthals, and humans from the past and the future, along with mysterious, dangerous obelisks and other hazards. In all, the novel is breezy, nerdy fun, an action-packed adventure tale with its tongue lodged firmly in its cheek and its geek-culture credentials proudly to the fore.

Similarly in search of a lost relative is Piper “Pip” Screed in Opposite World by Elizabeth Anne Martins (Flame Tree Press £20/$26.95). Keen to learn the answer behind her mother’s mysterious disappearance some 15 years earlier, Pip immerses herself in The Reverie Cloud, a combination of virtual reality simulation, role playing game and lucid dreaming. Exploring the landscape of her subconscious unearths missing memories but also puts Pip at the mercy of Nyxyn, the corporation responsible for the technology.

Martins has fun meticulously unpeeling the onion layers of Pip’s mind and showing how truth and trust can be malleable concepts. Opposite World reads rather like a course of psychotherapy with SF trappings, its narrative given impetus not so much by storytelling drive but by the protagonist’s desire, relatable and common to many, to understand herself better and heal the mental and emotional fissures left by her past.

Unexplained death likewise rears its head in Lorraine Wilson’s The Salt Oracle (Solaris £18.99). This novel is set in the same world as the author’s We Are All Ghosts in the Forest (2024), wherein the internet has collapsed — an event known as the Crash — but the digital phantoms it has left behind linger on.

The new book falls broadly into the category of Dark Academia but also incorporates a murder mystery plot. Its setting is the Bellwether, a seaborne college afloat in the Baltic. Here is housed the Oracle, a girl who can communicate with the aforementioned ghosts and whose insights help keep the waters thereabouts safe.

The Oracle becomes the pawn in a power struggle that costs the life of Boudain Caron, mentor to the book’s heroine Auli. In investigating his murder, Auli places herself in harm’s way, which is so often the lot of sleuths who have a personal involvement with the victim; but the Bellwether is endangered too, as the seas around it start to turn hostile and spawn spectral folkloric monsters.

There’s a great deal to like about The Salt Oracle, not least Wilson’s willingness to blend and bend genres and her often exquisite writing. The novel is a little overlong, but this is more than compensated for by its originality and the rich seam of maritime mythology it mines.

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X