Violent underwater ‘storms’ are melting Antarctica’s ‘Doomsday Glacier’ from below, a concerning new study warns.

Much like hurricanes above land, the swirling vortexes are formed in the open ocean when waters of different temperatures and densities collide.

They travel towards Antarctica where they melt the Doomsday Glacier, officially known as Thwaites Glacier, as well as the Pine Island glacier, both in West Antarctica.

Study author Mattia Poinelli at the University of California, Irvine, said the vortexes ‘look exactly like a storm’ and are ‘strongly energetic’.

‘There is a very vertical and turbulent motion that happens near the surface,’ Dr Poinelli told climate organisation Grist.

‘In the future, where there is going to be more warm water, more melting, we’re going to probably see more of these effects in different areas of Antarctica.’

Glaciers are slow–moving rivers of ice – some hundreds of thousands of years old – that reflect the sun’s rays back into space and store valuable freshwater.

If they all completely melted, global sea levels would suddenly rise, flooding cities, displacing millions of people and destroying infrastructure.

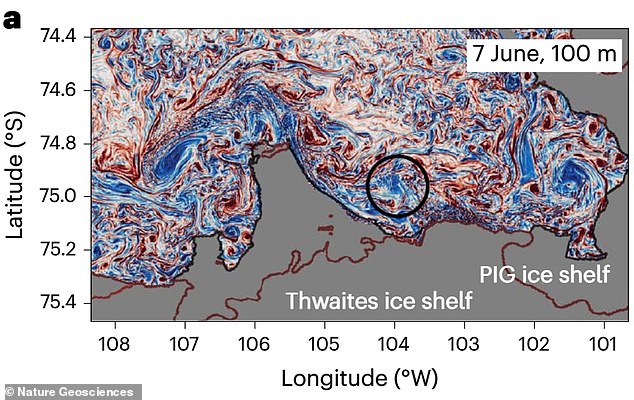

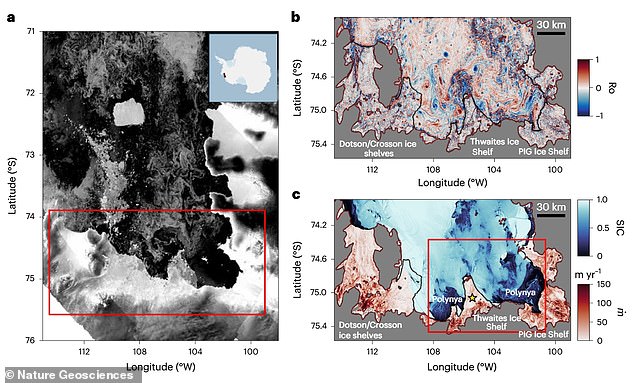

The experts found evidence of storm–like circulation patterns beneath Antarctic ice shelves that are causing aggressive melting beneath the ‘Doomsday Glacier’, officially known as Thwaites Glacier, and the Pine Island glacier (PIG)

For the study, researchers relied on ‘realistic’ simulations from computer modeling as well as moored devices, which provided high–resolution observations below the ice.

The experts found evidence of the storm–like circulation patterns beneath the ice shelves – the floating extensions of glaciers that have flowed from land out onto the ocean surface.

These swirling ocean currents are called ‘submesoscale’ meaning they measure between 0.6 and 6.2 miles across (1 and 10 kilometres).

They regularly form in the open ocean, propagate towards the Doomsday Glacier, intrude its cavity, and then aggressively melt the ice from below.

According to the experts, the storms draw up deeper, warmer water from the ocean’s depths into the cavity while pushing away colder freshwater.

More ice shelf melting generates more ocean turbulence, which in turn causes yet more ice shelf melting – something of a vicious cycle.

The process is ‘ubiquitous’ year–round, occurring regardless of the season, although the team found elevated activity in June.

‘In the same way hurricanes and other large storms threaten vulnerable coastal regions around the world, submesoscale features in the open ocean propagate toward ice shelves to cause substantial damage,’ said Dr Poinelli. ‘[They] cause warm water to intrude into cavities beneath the ice, melting them from below.’

Nicknamed the Doomsday Glacier, Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica is one of the largest and most unstable glaciers on Earth

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet is home to Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers, which are responsible for more than one–third of the total ice loss in Antarctica. Over recent decades, these glaciers have undergone widespread thinning and rapid retreat, the team say

What is the Doomsday Glacier?

The Thwaites glacier currently measures 74,131 square miles (192,000 square kilometres) – around the same size as Great Britain.

It is up to 4,000 metres (13,100ft) thick and is considered key in making projections of global sea level rise.

The glacier is retreating in the face of the warming ocean and is thought to be unstable because its interior lies more than two kilometres (1.2 miles) below sea level while, at the coast, the bottom of the glacier is quite shallow.

The collapse of the Thwaites Glacier would cause an increase of global sea level of between one and two metres (three and six feet), with the potential for more than twice that from the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

<!- – ad: https://mads.dailymail.co.uk/v8/us/sciencetech/none/article/other/mpu_factbox.html?id=mpu_factbox_1 – ->

Advertisement

The team say the storm–like circulation patterns account for as much as 20 per cent of total melting under the surface of the sea in the region.

This finding has major implications for global sea level rise projections; without taking into account undersea storms they could be drastically underestimated.

Despite being largely overlooked ‘in the context of ice–ocean interactions’, these underwater storms are among the primary drivers of ice loss, the academic added.

‘This underscores the necessity to incorporate these short–term, ‘weatherlike’ processes into climate models for more comprehensive and accurate projections of sea level rise,’ he said.

Thwaites and Pine Island glacier are both part of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet – a rich reservoir of precious frozen freshwater measuring about 760,000 square miles.

Since the 1980s, Thwaites and Pine Island have been described as part of the ‘weak underbelly’ of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

Not only are they vulnerable to collapse even under relatively little warming, but if they go, the entire ice sheet is likely to eventually follow.

If it were to collapse, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could raise global sea level by up to three metres (around 10 feet).

Antarctica is home to a number of ice shelves marked out in this map, including Amery, Shackleton and Ross. The formations are also found along Arctic coastlines

Ice shelves are permanent floating sheets of ice that connect to a landmass. Pictured is the Ross Ice Shelf, the largest ice shelf of Antarctica

In a future scenario of sea level rises, cities and towns are flooded more easily, meaning people would have to flee their homes and move further inland.

Other small island nations might be gradually plunged underwater entirely, forcing inhabitants to emigrate.

While the team say the 21st–century rate and extent of ice loss from West Antarctic Ice Sheet ‘remain uncertain’, greenhouse gas emissions mean it’ll likely be a matter of hundreds of years rather than thousands.

‘Ongoing changes have raised concerns about a future collapse of the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet,’ the experts say in their paper published in Nature Geosciences.

‘Submesoscale motions are ubiquitous year–round in the Amundsen Sea Embayment [location of Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers and one of the primary sites of rapid ice melt on the ice sheet].

‘As future climate warming implies greater ocean–induced melting, these events will become increasingly frequent, with far–reaching implications for ice–shelf stability and global sea–level rise.’

HOW IS GLOBAL WARMING AFFECTING GLACIAL RETREAT?

Global warming is causing the temperatures all around the world to increase.

This is particularly prominent at latitudes nearer the poles.

Rising temperatures, permafrost, glaciers and ice sheets are all struggling to stay in tact in the face of the warmer climate.

As temperatures have risen to more than a degree above pre-industrial levels, ice continues melt.

For example, melting ice on the Greenland ice sheet is producing ‘meltwater lakes’, which then contribute further to the melting.

This positive feedback loop is also found on glaciers atop mountains.

Many of these have been frozen since the last ice age and researchers are seeing considerable retreat.

Some animal and plant species rely heavily on the cold conditions that the glaciers provide and are migrating to higher altitudes to find suitable habitat.

This is putting severe strain on the ecosystems as more animals and more species are living in an ever-shrinking region.

On top of the environmental pressure, the lack of ice on mountains is vastly increasing the risks of landslides and volcanic eruptions.

The phenomena is found in several mountain ranges around the world.

It has also been seen in regions of Antarctica.