This is the last collection of photos I have, so the feature won’t be available until I get new pictures. Just sayin’. . . .

But today we have a photo-and-text essay from Athayde Tonhasca Júnior. His captions and IDs are indented, and you can enlarge the photos by clicking on them.

The unfairly despised

The renowned entomologist, evolutionary biologist, naturalist, conservationist and target of woke troopers Edward O. Wilson popularised the concept of biophilia (love of life), the intuitive affiliation humans have with nature that is expressed by our attraction to animals, plants, landscapes and other natural things. For Wilson, biophilia is an evolutionary trait ingrained in the human personality. While his hypothesis has been supported by anecdotal and quantitative evidence, not all forms of life are equally cherished. Snakes and spiders, for example, evoke fear and revulsion in many people, responses that are also embedded in our brains and shaped by ancestral fears of animals that could harm us.

Little Miss Muffet being scared by a spider, by William Wallace Denslow © Wikimedia Commons:

Among the many types of animal phobias (the irrational, exaggerated and uncontrollable aversion to certain creatures), entomophobia is one of the most common across countries and cultures. Many theories have been proposed to explain the negative emotions triggered by insects (Lockwood, 2013), but anthropologist Hugh Raffles was spot on in describing entomological scenarios that can trigger primordial horrors: “there is the nightmare of fecundity and the nightmare of the multitude; there is the nightmare of unguarded orifices and the nightmare of vulnerable places; there is the nightmare of swarming and the nightmare of crawling; there is the nightmare of awkward flight and the nightmare of clattering wings; there is the nightmare of entangled hair and the nightmare of the open mouth.” (Raffles, 2010).

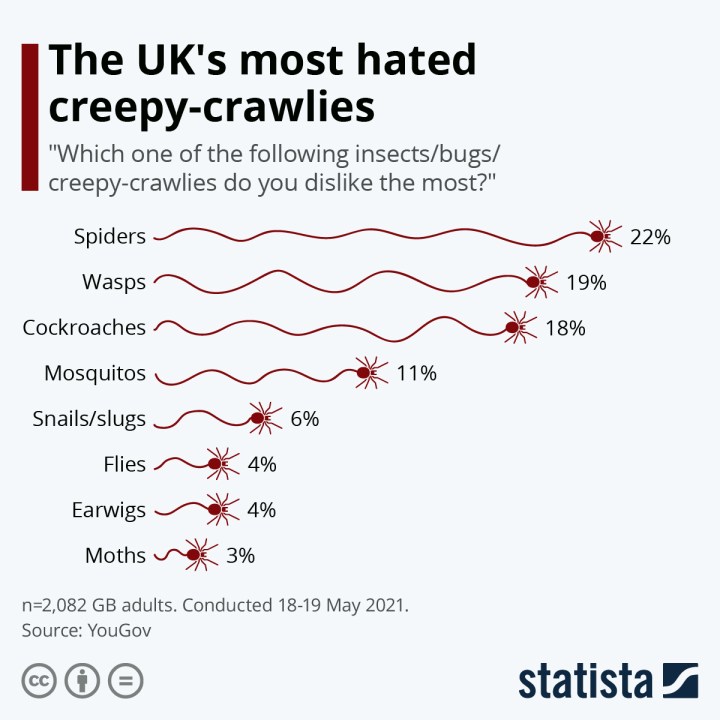

The fear of being stung, bitten, or swarmed by flying living things help explain why, in a 2021 survey, Britons placed spiders and wasps at the top of the list of unpopular invertebrates. The survey also revealed an interesting aspect of human perceptions and attitudes: largely harmless animals are more disliked than mosquitoes, the world’s most lethal to humans.

Results of a YouGov 2021 survey © Statista:

Cockroaches came third on the British dislike scorecard, surely only because they are not that common in the country. In warmer places, where people are likely to have had close encounters with cockroaches, these insects shoot up to the top of the list, and by a considerable margin. A shiny, greasy appearance, probing antennae, erratic skittering and a sewage aroma are off-putting enough, but their flying and occasional accidental entanglement in one’s hair can send the toughest character shrieking away. On top of that, domestic cockroaches are associated with filth, which triggers an uncontrollable feeling of disgust. For psychologist Mark Schaller, this reaction reflects our Behavioural Immune System, a set of innate responses shaped by evolution to identify signs of contamination by pathogens and avoid disease. If something looks like it could make us sick, we flee from it.

A sight to make many people cringe: an Oriental cockroach (Blatta orientalis) sharing our table © H. Zell, Wikimedia Commons:

The upshot of all this bad PR is that many people loathe cockroaches. Fervently. And yet, there’s more to cockroaches than abjectness and pestilence.

There are some 4,500 described species of cockroaches, of which 25 are synanthropes (organisms adapted to live near humans) and considered pests. The remainder are found in a variety of natural ecosystems, predominantly in tropical and sub-tropical regions. They live among leaf litter, rotting wood, underneath tree bark and among vegetation, feeding on almost anything of nutritional value. Together with termites, which belong to the same order Blattodea, cockroaches are highly beneficial by accelerating the breakdown of organic matter and the release of nutrients into the environment.

Florida woods cockroaches (Eurycotis floridana) munching away on rotten wood © Happy1892, Wikimedia Commons:

And another ecological role of cockroaches is slowly becoming better known: pollination.

Some plants and cockroaches share the same type of habitat: shaded, humid spots under the cover of thick vegetation. These places are not the best for recruiting the usual pollinators such as bees, hover flies and moths. But a cockroach may be the ticket for efficient transport of pollen from one plant to another. And that’s an opportunity not missed by Balanophora tobiracola, a parasitic flowering plant from Yakushima Island, Japan. Margattea satsumana cockroaches are seen scurrying all over B. tobiracola plants, suggesting they may do more than feed on pollen and nectar. Indeed, exclusion experiments – where plants accessible to visitors are compared to those with no access – revealed that cockroach visitation enhanced pollination, while the contribution of moths, flies and beetles was negligible (Suetsugu, 2025).

A M. satsumana cockroach visiting a B. tobiracola plant © Suetsugu & Yamashita, 2022:

Cockroach pollination on a Japanese island is not an isolated case. In French Guiana, the cockroach Amazonina platystylata is the main pollinator of Clusia aff. sellowiana (a potentially new species related to Clusia sellowiana). The cockroaches have no specialised pollen-collecting structures, but their bodies are coarse enough to retain pollen grains and transport them from flower to flower (Vlasáková et al., 2008).

An A. platystylata cockroach and a Clusia flower © Cockroach Species File and Scott Zona (Wikimedia Commons), respectively:

Cockroaches are known to pollinate some ten other plant species, so they are not exactly major players in plant reproduction. But part of the reason for these meagre figures is lack of information. Shy, nocturnal insects living deep down in thick forests are not observed very often, much less researched. Cockroach pollination also illustrates plants’ capability to adjust and make the best of challenging settings; when run-of-the-mill pollinators are not around, a busy, inquisitive cockroach would do just fine.

Not all cockroaches are unappealing to us, like the Mardi Gras cockroach, aka Mitchell’s diurnal cockroach (Polyzosteria mitchelli), from Australia © Evelyn Virens, iNaturalist: