You’ll know a lot about Mick Jagger.

Singer from the Rolling Stones. Half of, along with Keith Richards, one of the most successful songwriting partnerships in music. Cultural icon, however you want to interpret that. Became a father at 73. Turquoise blouse wearer of the year, 1985.

What you might not know about Mick Jagger is that he was a pioneer of streaming sport over the internet. Specifically, cricket.

In the late 1990s, when most people just about had an email address and the smartphone with even one G, never mind five of them, was just a twinkle in a mad inventor’s eye, the internet was still regarded by many as the preserve of the nerd. Most of the record industry either treated it as an irrelevance or, with the advent of Napster and other streaming services a few years later, a threat.

But Jagger was an early adopter, or at least he was someone who spotted the internet’s potential while others retained suspicion.

The Stones let fans vote on their setlist via their website, and experimented with live webcasts of their concerts — slightly chaotic, seat-of-the-pants affairs from a technological point of view, but an early glimpse into what was possible on the information superhighway.

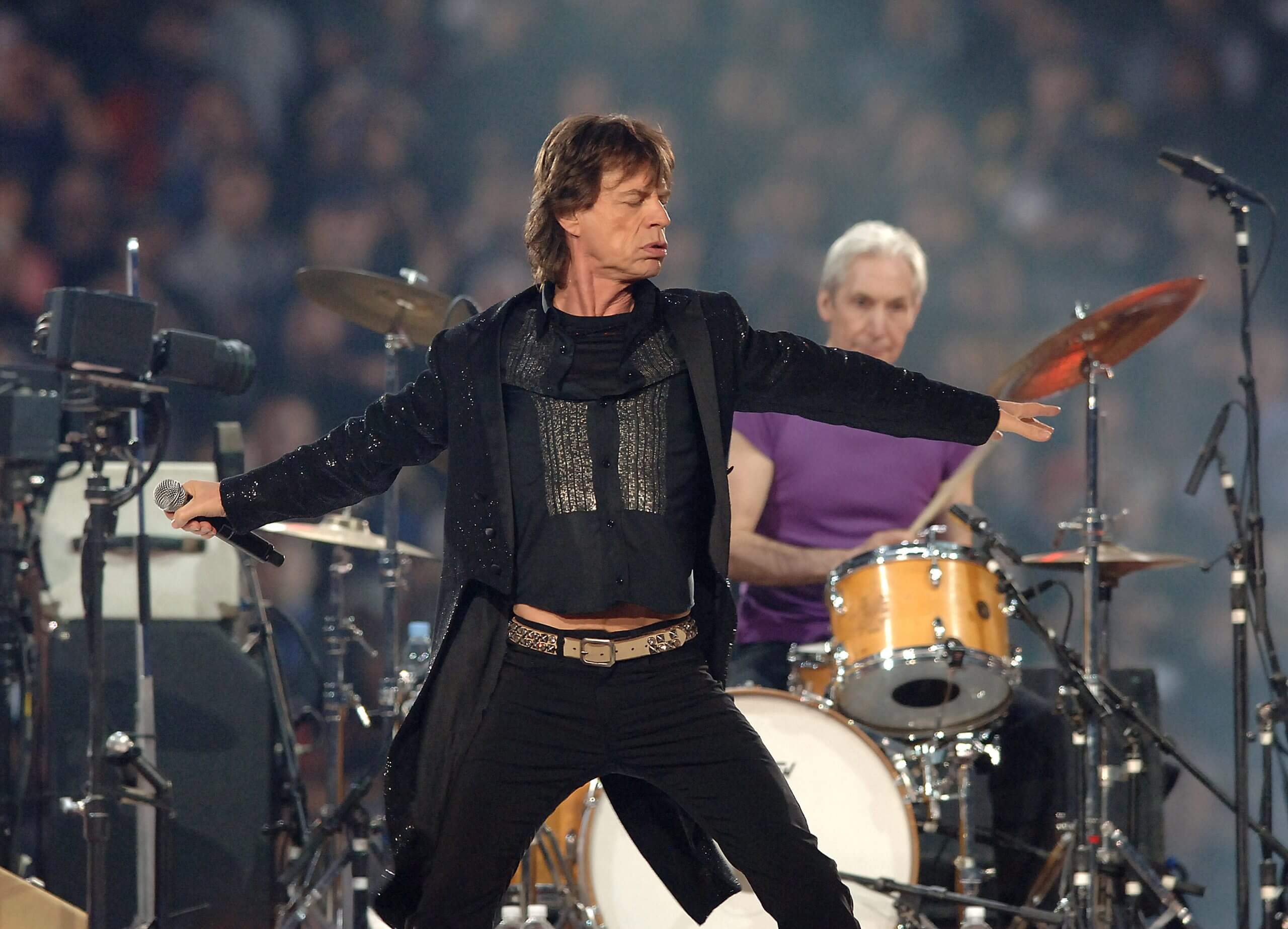

Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones perform at half-time during Super Bowl XL in February 2006 in Detroit (Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images)

Jagger is also a cricket nut.

When England play a Test match at Lord’s, as the cameras scan the crowd looking for notable attendees, down the years, there have been a few famous faces about whom commentators will reliably remark “they love their cricket”: Stephen Fry, John Major, the late Michael Parkinson… and Jagger. He played the game at school and, by all accounts, was pretty good; he was apparently starstruck when attending an official lunch during a Test match in the early 1980s, in awe after meeting childhood heroes such as Denis Compton and Godfrey Evans.

His choice of the Caribbean island Mustique as a holiday bolthole was as much informed by the West Indian passion for cricket as it was the sunshine and solitude.

So when he discovered that nobody was planning to broadcast the Akai-Singer Champions Trophy — a relatively minor one-day tournament in December 1997, held in Sharjah and featuring England, Pakistan, India and West Indies — these two interests converged. He duly did the only logical thing.

He formed a company and broadcast it himself.

“Jagged Internetworks is a company founded to produce and promote sports and entertainment events on the Internet,” he said in a rather stiff statement announcing the venture. “The first sport we selected was cricket, because of my passion for the game.

“This is the future of sports information. In a few years from now, the internet will be a huge player in sports broadcasting across the globe.”

A young Mick Jagger returns to his seat at the Oval in London to watch England take on Australia in August 1972 (Central Press/Getty Images)

“He got it, and he got all the possibilities really quickly,” says Ted Mico, who had worked with the Stones in some capacity since 1994 and helped form Jagged Internetworks. “So spin forwards, and when you’re on the road, and you don’t have access to Sky Sports or Channel 4, you’re a huge cricket fan, then what can the internet do? There’s a problem that could be solved here.”

To solve that problem, Jagger needed a platform. Just sticking a stream on some random website wasn’t going to cut it. Which is why Cricinfo founder Simon King’s phone rang one day.

“It was just a cold phone call saying Mick Jagger wants to do this,” says King, matter-of-factly. “They asked: ‘What do we need to do to make it happen?’. It wasn’t unusual at the time. We were one of the hottest properties on the internet.”

Indeed, they were. Cricinfo started life as a sort of proto-message board on which people shared information and cricket scores, but by the late 1990s, it had become something of a juggernaut. King recounts that for a while they were growing by 950 per cent, year-on-year. By the time of that phone call, they were already providing live text commentary and scorecards on the website, allowing people from all over the world to follow games in a way that simply wasn’t possible before.

It was thus the logical place to go if you wanted to stream cricket matches.

At the time, it was framed as a sort of rich man’s hobby, something that Mick Jagger was doing because he was Mick Jagger and he could. Some celebrities collect cars, some buy islands. Jagger purchased the rights to broadcast semi-obscure cricket matches over the internet. The impression given was that Jagger was only really doing this so he could watch or listen to the cricket when he was on tour with the Stones.

Which had at least an element of truth to it. “Bringing cricket to the masses was good,” says Mico, “but bringing cricket to the hotel room when you’re on the road for a year or two was even better.”

But it was a genuine business idea, too. As Jagger said in his statement announcing the venture, he wanted this to just be the start.

Was Mick Jagger an internet visionary? (Jonathan Daniel/Getty Images)

It probably goes without saying that Jagger wasn’t quite writing code and immersing himself in the nuts and bolts of the still nascent technology, but he was still pretty hands-on.

“A fair bit,” says King, when asked how closely Jagger was involved. “He was very interested in it, so he put a lot of effort in. He said: ‘What do I have to do to make this happen?’. I told him he had to buy the rights, which Cricinfo at the time didn’t have the sort of money to do. We had the technology and the know-how of how to stream it.”

Mico goes a step further. “He was very, very hands-on. He was intimately involved in every aspect, from the rights deals all the way through to sponsorship and the technology, some of which was very bleeding-edge at the time. He wanted to know everything about it as it was his reputation on the line.”

Nobody can quite remember how much Jagger paid for the rights, but the words “not much” came up repeatedly. Which is largely because internet broadcast rights weren’t really a thing at the time, or at least not a thing that anybody really cared about. Jagger would set up meetings and calls, looking for sponsors and various other things. For obvious reasons, he would be much more likely to get a “yes” than the average Joe.

A company called WorldTel sold them the rights, and they would also provide the actual broadcasts, which is to say the cameras, commentators, and so forth. That first tournament featured commentators such as former West Indies fast bowler Michael Holding, the great India batter Sunil Gavaskar, and Geoffrey Boycott, who played 108 Tests for England, but they didn’t really know they were essentially working for Mick Jagger. Companies such as WorldTel sell their broadcasts to all sorts of places around the world.

Sharjah Cricket Stadium, in the UAE, hosting the 1997 Akai-Singer Champions Trophy (Stu Forster/Allsport

A deal was done with Real Networks to host the stream, which would then be given to Cricinfo to embed on a page on their website. And it’s fair to say that they didn’t quite realise what they were getting themselves into.

Real Networks had done some early streaming of this sort for the NBA, so they thought they could handle a quaint old colonial sport like cricket. But one of the games they broadcast was India against Pakistan, the biggest rivalry in world cricket between the two most passionate fanbases in the game. The demand was such that they took down the server. A call came from someone at Real Networks: “What the f*** is this ‘cricket’?”

“They said the previous busiest thing they had was Monica Lewinsky’s live testimony,” adds King. “And we got more than that.”

“There was an underestimation on everyone’s part on how popular cricket is and the lengths fans would go to get access to games,” adds Mico. “Especially in America, where the technology was centred. So when the numbers came in, it was staggering. The India-Pakistan-Australian diaspora in the States is huge and people from around the world also tuned in.

“Quite by accident, Jagged Internetworks had unlocked huge demographic and commercial potential, but the initial intent was just to watch the cricket!”

It is worth noting that when we say streaming, we of course aren’t talking about the beautiful 4K clarity that you’d get on Netflix or similar today. The broadcast essentially consisted of audio commentary with still images every five seconds, like a sort of deluxe slideshow. “There was enough bandwidth at that time for audio, but video was a pipe dream,” says King.

“It was very much an on-the-fly thing,” says Mike Whitaker, one of the people who was responsible for keeping the technological side of things running in Cricinfo’s early days. “We were running at the ragged edge of what our system could do. This was probably our first real foray into, ‘The engine cannae take it, captain’ territory.”

Even if there was bandwidth, most people at that time used dial-up internet: those old enough to remember will be able to close their eyes and remember every note of the sounds the modem made as it connected via their phone line. Those not old enough to remember, ask your mum or something.

We could get deep into the weeds of the technology here, but let’s instead just summarise: it was like the internet you know today, only much, much, much slower. Downloading a single still image was often a challenge, so even if live video was possible, it wouldn’t have actually reached many people.

Essentially, the idea was a few years ahead of the technology. “It was way ahead of its time,” says Whitaker. “We were probably a decade ahead of things.”

England’s Graham Thorpe, Adam Hollioake, and Matthew Fleming celebrate victory at the Akai-Singer Champions Trophy (Graham Chadwick/Allsport)

The eventual output was, considering all of the technological barriers, pretty good.

There were some issues with delays to commentary, but you can get that with modern broadband. One criticism, raised by Stephen Brenkley in The Independent, was that the commentators were describing the action as they would for television, which is to say, on the assumption that the viewers could see what was happening, which, given the limited nature of the visuals, was not ideal.

After that first series, Jagger wanted to go further. King recalls being invited to Berlin during the Stones’ ‘Bridges To Babylon’ tour, to meet with Jagger about future plans. Only because this was Jagger, the meeting took place in a Berlin nightclub, post-show.

“I sat at the soundstage at the Olympic Stadium and met the rest of the Stones,” he says. “I was more of a Beatles fan; I didn’t know their names. I was ushered in and Mick introduced me to the rest of the band.”

Again, King says this sort of thing was not especially unusual given the pace of things at the time. “I was so focused at that time on holding onto this bucking bronco that was Cricinfo, that was just expanding at this massive rate all over the place. The previous week, I’d had the crown prince of Russia holding open a plane door for me. We’d helicoptered down to Monaco.”

The rest of the Stones didn’t really take much interest. Drummer Charlie Watts, another cricket fanatic, watched the end product but didn’t get involved with the business. Keith Richards and Ronnie Wood were… probably busy elsewhere.

Mick Jagger is a huge cricket fan, as was the Stones’ drummer, Charlie Watts (Theo Wargo/Getty Images)

More broadcasts came. There was an India-Pakistan-Bangladesh tri-series held in Dhaka. A Pakistan tour of Zimbabwe. The 1998 England tour of West Indies, which featured the infamous Test at Sabina Park, Jamaica, that was called off after just 62 deliveries because the pitch was unsafe.

But it all came to an end in the first half of 1999.

There seemed to be no huge fallout, no dramatic close to it all. Jagger had other things occupying his time. Cricinfo was about to receive investment that would eventually lead to the first of a few takeovers, and was pitching to be the official site of the 1999 World Cup.

Mostly, though, it came down to money. The Jagger-Cricinfo partnership had shown other people, media companies with deeper pockets, that there was an audience for cricket on the internet, and they took over.

“We used Cricinfo as the loudspeaker,” says Mico. “It was a lot of work. Well worth it because it was fun watching. Could we have competed with big media companies? I don’t know. We made the market, then the market took over.”

“It was too early,” says King. “Had he been prepared to sink in $25million-$50m (£19m-£38m) and wait, he probably could have had broadcast.com and sold it for $5billion.”

Nevertheless, the partnership showed what was possible. These days, Cricinfo is owned by ESPN and does broadcast some audio-visual coverage. King was forced out in 2003 when Wisden took over, but looks back now like a proud parent. “Cricinfo is now doing pretty much everything that I wanted it to do.”

And Jagger… well. “I think the word pioneer is thrown around a lot, but he definitely got it and was on the pioneering side for sure,” adds Mico.

The Rolling Stones. Mick and Keith. Cultural icon. Father at 73. The turquoise blouse. And internet streaming pioneer.