Reconstructed vegetation

Analysis of spores, pollen and phytoliths allows to reconstruct predominance of herbaceous communities (sedge, sedge-grass, and grass-forb). The families of herbs and dwarf shrubs identified by pollen are represented by a significant number of species of different ecological confinement. It suggests the existence of meadows with varying moisture degrees. The mass content of pollen of grasses and sedges and the forms of phytoliths Crenate and Acute bulbosus, characteristic of meadow grasses, is evidence of their predominance in the vegetation cover.

The presence of forb pollen in the spectrum is low. This may be due to the low pollen productivity of these plants under severe climatic conditions and their transition to vegetative reproduction 9. The high participation of forbs in the vegetation is emphasized by the noticeable amount of undeveloped pollen and phytoliths Elongate entire that are typical for dicotyledonous herbs and partly grasses. The mentioned forms of phytoliths are formed in the columnar parenchyma of leaves of dicotyledonous grasses, although some of them could have been formed by monocotyledonous plants. It is possible that the predominance of Elongate entire forms is due to their solid structure facilitated their preservation in sediments 10. These forms are poorly informative, but in this case they emphasize the significant role of meadow forbs and grasses in the vegetation. The presence of the Elongate sinuate and Bloky parallelepipedal forms confirms this conclusion.

Albeit insignificant, the finds of Papillate phytoliths of wetland sedges suggest the presence of tundra meadows on moist substrates. The existence of such habitats found on the banks of lakes and rivers and in lowland meadows is also indicated by Sphagnum spores and minor herb taxa Valeriana and Ranunculaceae, growing in the conditions of sufficient or excessive moisture. These conditions could have developed as a result of an increase in the thickness of seasonally thawed layer due to the melting of polygonal ice wedges. The result of the latter is also activation of slope and erosion processes. The presence of scree slopes, well-drained and/or disturbed and undeveloped soils is diagnosed by the findings of sagebrush Artemisia and rock spike-moss Selaginella rupestris, phytoliths Elongate dentate, characteristic for grasses growing on dry substrates and also Glomus fungi which are indicator of active soil erosion and the prevalence of aeolian processes in open landscapes 8.

Due to its low productivity, poor distribution and easy destructibility 11 even small amount of larch pollen is conventionally taken to indicate sparse trees or small patches of larch forest in the reconstructed vegetation. Large number of specific forms typical for Larix wood found in plant detritus is additional evidence for larch in the region. These forests were contributed by shrub birch, which also can form streamside thickets in tundra. Mesic forbs (Ranunculaceae, Ericaceae) and mosses were in the ground cover of the larch forest.

Based on the small pollen content of Alnus, Pinus s/g Haploxylon (the latter indicates the presence of the shrub Pinus pumila (Pall.) Endl. in Quaternary records from northeastern Asia), and Betula sect. Albae from the tree species of birch it is difficult to conclude about their roles in the vegetation. Trees and shrubs of above genera produce a large amount of highly wind transportable pollen therefore it can reflect long-distance pollen transport, depending upon atmospheric conditions. The low percentages of mentioned pollen also could suggest the rare occurrence of scattered thickets of alder and occasional dwarf pine and birches in the understory of larch forests.

The amount of willow pollen in the spectrum is small. Due to entomophily and dioecy, its content even in subfossil spectra is low, provided that the sample is collected directly near the plant 12. Willow may have formed thickets along river banks and on lower slopes.

Trace amounts of dung-inhabiting fungal spores of Sordaria and Gelasinospora likely indicate the presence of grazing animals. Gelasinospora also provides the evidence of fires.

The spectrum is interpreted as a mix of a floodplain mature larch forest restricted to the valley bottom and lower elevation slopes and mesic sedge-grass-forb meadows with a mosaic of moist to xeric habitats.

The sediments were accumulated under wetter conditions as evident by notable amounts of remains of cyanobionts, diatoms, sponge spicules, finds of green algae Botryococcus and Pediastrum, charophytic algae Zygnema and Spirogyra, stomatocysts of Chrysophyceae algae, phytoliths of wetland sedges, pollen of water plants and plants of moist substrates.

These environments could have existed in shallow ponds or swamps, formed under the conditions of increased moisture from groundwater in the presence of waterproof of permafrost soils in the relief depressions or on a flooded river bank.

Our conclusions are quite consistent with the results of macrophytofossil analysis of colluvium deposits in the studied locality, which allowed to identify Salix sp., Larix sibirica Ledeb., Betula sp., Cladonia portentosa (Dufour) Coem., and C. rangiferina (L.) Weber ex F.H. Wigg. and the analyses of fossil humus and mammoth coprolites, in which Bryum sp., Polypodiaceae, cf. Carex sp., Eleocharis sp., and cf. Cicuta virosa L. were reported 4.

The palynological data from the MIS 3 deposits of the Badyarikha River sites and other localities of the central Indigirka basin 4 document changes in the landscape cover over the past about 50 ka. They indicate taiga forest and parkland-steppe ecosystems within the central Indigirka basin during the warmest MIS 3 interstadial interval (~ 50–45 ka BP). At a later stage (after ~ 40 ka BP), the ecosystems of the forested valleys transformed into a larch-dominated forest-tundra, with thickets of alder, willow, and dwarf birch, floodplain meadows, marshes, and herbaceous grasslands, and our results show that the Siberian Homotherium existed in such environments. At the end of the interstadial (~ 30–25 ka BP), the shrub- and grass-dominated herb-tundra-steppe was formed in the region 4.

Palynological data for the second half of MIS 3 (ca. 42,000–30,000 years cal BP) suggest that the landscape on the territory of Yana-Indigirka-Kolyma lowland supported open areas with herb-dominated associations. Plant communities were represented by forb-grass-sedge, sagebrush-grass-sedge, grass-sagebrush-forb associations, xeropetrophyte associations, tundra associations on moist soils along riverbanks and in the river valleys and willow thickets 13. Larix forests were widely present from Priokhot’ye to the northern Yana-Indigirka-Kolyma lowlands in these times 14. These forests were probably open woodlands restricted to lower elevations in the river valleys or isolated stands in favorable sites.

Homotherium

habitats

The habitats of Homotherium were very diverse, and the range of this genus included Africa, Eurasia and America 15. Judging by the structure of the skeleton, which reflects a cursorial adaptation (at moderate speeds for large distances), Homotherium did not live in dense forests, but preferred more open spaces 16. Analyses of dental microwear textures and stable isotopes of tooth enamel indicate that this likely social predator preferred soft and tough flesh of open-habitat prey, including bison, horses, and juvenile mammoths 17,18.

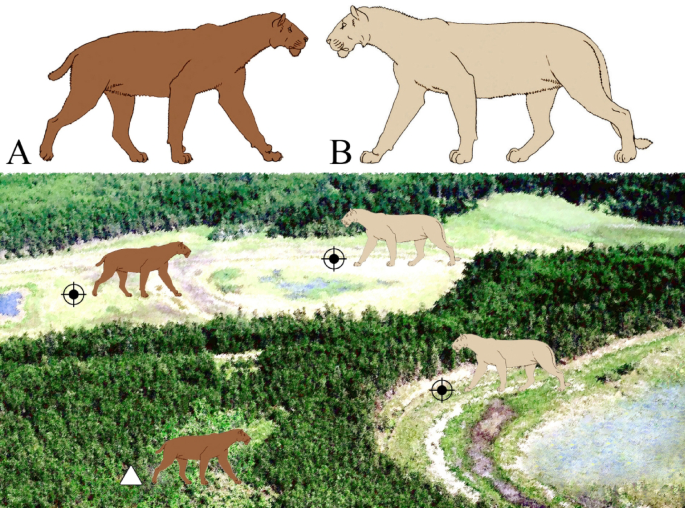

Interesting results were obtained by analyzing the evolutionary history of late representatives of Homotherium in context of their possible competitive relationships with other large predators 19,20. In the Pleistocene of Europe, the main competitor of Homotherium for hunting grounds and prey was the cave lion, Panthera spelaea, which was somewhat larger than the modern lion. The cave lion’s size, strength, and social lifestyle gave it a dominant position in the guild of large carnivores. It is really unknown how intense was this competition (scimitar-toothed cats were probably diurnal hunters 17, while cave lions were more active at night). Nevertheless, these similar-sized species (with weights of 100–220 kg for the late representatives of Homotherium, and 140–300 kg for Panthera spelaea spelaea, see Fig. 6) clearly interacted aggressively, and Homotherium probably found a way to reduce this competitive pressure by avoiding lion favorable habitats 20,21. The cave lion inhabited predominantly plains and river valleys 22. Open habitats were preferable for Homotherium hunting technique, but competition from the cave lion have forced it to seek moderate cover, which was provided by a mosaic of woodlands and grasslands 16. In northern Siberia, these mosaic landscapes were the arctic tundra steppe and northern forest-tundra areas, where low larch formed sparse forests with patches of meadows 13,14.

Reconstructed habitat pattern of the co-existed Late Pleistocene saber-toothed cat, Homotherium latidens (A), and cave lion, Panthera spelaea (B), on Badyarikha River in northern Yakutia. Designations: black crosshair, hunting grounds of both homotheres and cave lions; white triangle, den sites of homotheres. Not to scale. The extinct felid outline images after Antón et al.16.

In the Late Pleistocene of Eurasia, representatives of Homotherium may have existed at low population densities. This effectively put them below the “fossil detection threshold” and left very few remains in the fossil record 23. The same has been proposed to explain the low prevalence of relict Homotherium in the Americas 24,25. These ranges were limited to small habitats and may even have been refugia. Anyway, the discovery of the Badyarikha saber-toothed cat mummy proves that during the Karginsky interval, correlated with MIS 3 (at least until around 37 ka BP) the Homotherium population survived in this region of northern East Siberia. Judging by found bone remains, the cave lion lived there at the same time. Consequently, these two large felid predator species co-existed in this region. The find of a three-week-old cub, indicating the presence of a den, identifies this area as the domain of Homotherium. It can be assumed that this situation was related to local environments. Probably, such a suitable habitat was the reconstructed mature larch forest, which served as a shelter for adult saber-toothed cats and a hidden cradle for their cubs (Fig. 7).

Saber-toothed cat’s cradle: Siberian Homotherium cubs at the edge of a larch forest. Artistic reconstruction by P. Mitroshkina (with scientific consultation by A.V. Lopatin).